A New Obsession for Spotify's Former Chief Economist: A Conversation with Will Page

Will Page has been on the forefront of music streaming for the last two decades. We sat down to talk about what he thinks about the biggest problems in the industry today.

Every conversation you have about music streaming comes back to Will Page. After a more than a half decade at PRS, Page spent nearly a decade as the Chief Economist at Spotify. During those years, he had a front row seat to how every piece of the music industry, from licensing to royalties, was evolving in the streaming age.

Page stepped down from Spotify in 2019 to write his first book Tarzan Economics: Eight Principles for Pivoting Through Disruption. Since then, he’s been one of the most sought-after thinkers on how to fix the latest round of problems that plague the music industry. Over an hour, Page and I spoke about how his thinking on royalties has changed, why collective management organizations are a great place to start your music career, the perils of live music, and the need to raise streaming prices. If you enjoy our conversation, get a copy of his book by clicking the button below.

A Conversation with Will Page

I want to begin with a topic you’ve been hot on lately: streaming payout models. Over the years, your thinking on this has changed. Explain to me where you currently stand on how streaming payouts should work.

My thinking has changed. But if the data changes, you need to change your position. So, I’ll walk you through a few models.

Pro Rata: When I first started in music, everybody from Spotify to ASCAP used the pro rata model. It’s an efficient model and has served us well. You get 1% of streams, you collect 1% of the royalty pool. Could it be fairer? Maybe. But there are tradeoffs.

User-Centric: This model says that if I pay $10 per month, then that $10 is only allocated to the artists that I listen to, not to all of the artists on the platform. That might seem fairer, but it’s more complex because you are considering each user individually rather than in aggregate.

Artist Growth: This was first presented by Paul Pacifico and was based on models of taxation. You take some royalties from the hyper-rich, distribute that to the poorer artists, and leave everybody else unchanged.

Thresholds: This would say something like, you don’t collect royalties unless you reach a certain number of streams. This idea upsets many people, but it has been the basis for music payouts forever. Collective management organizations have used thresholds to distribute payments for 100 years. And streaming services have also never paid out royalties unless a song crossed a 30-second threshold.

More recently, you’ve focused on a consumption-based model. As you just noted, currently a song only bears a royalty if it is played for more than 30 seconds. This new model you’ve been talking about would pay more if a song was listened to in full. Can you talk a bit about the contours of the model?

During a streaming economics inquiry by the UK government, I was pressed by parliamentarians about what we could do with streaming royalties. I noted how when the BBC plays “Bohemian Rhapsody”, they pay twice the royalty rate as when they play “You’re My Best Friend” because the former lasts twice as long as the latter. Everything on radio is duration-based. That’s the rule. So, why can’t streaming also be based on duration?

There had been some pushback against this idea because the scale of radio is so much smaller than streaming. They thought it would be too complex. That’s when I had a brainwave. Streaming services already measure duration. As you noted, songs don’t generate royalties until they are streamed for 30 uninterrupted seconds. I mentioned this to the royalty accounting teams. They said that’s not duration. It’s a threshold. Thresholds are easy. Duration is hard. So, my argument became that songs that are streamed completely should be worth more than those that are skipped before the end. That's a case for completion.

Do you think there are any weaknesses to this model?

I think the biggest criticism I've heard is that rewarding completion favors laid-back listening. If you play some music while you are showering, it’s always going to be played to completion. Do artist really want a model that favors that type of listening?

I would counter by noting that that isn’t necessarily a weakness. When we think about royalty payouts, we need to consider the artists, the platform, and the listener. Each of those entities has their own definition of what is fair. What I’ve found is that if the listener disagrees with something, everybody loses. Consumers like laid back listening. Our models should reflect that to some degree.

Do you think this also punishes longer songs?

People have argued that. But we actually see genres with longer songs, like jazz and classical, actually have higher song completion than those with shorter songs, like pop music. Overshadowing these nuances is some basic common sense: popular songs are more likely to be completed than unpopular ones as that's how music works! Think about it: indirectly, I'm introducing incentives to a payout model that's been unchanged for 23 years.

Do you think this model would also prevent fraud? I know the industry has a big problem right now where bots will play songs thousands of times for 31 seconds just to collect royalties. That takes money out of the pockets of legitimate artists.

Fraud is a tricky subject. I think the secret weapon against fraud is collaboration. It’s hard for a single platform to detect and prevent fraud when these bots can be coordinated across Apple and Spotify and Amazon and every other streaming service. The music industry needs something like what credit card companies have. Visa and Mastercard compete like crazy for market share, but the antitrust authorities let them come together to prevent fraud. I would love it if the streaming services and labels could come together to do that.

Adding this new threshold for completion would help, though. It allows us to both add a new layer of prevention by making it more difficult to reach the threshold, but it also removes an incentive to just stream songs for 31-seconds. Those 31 second click farms need to get whacked!

In 2021, you put out the book Tarzan Economics. One thing I like about that book is the subtitle: “Eight Principles for Pivoting Through Disruption”. You’ve been in the music industry two tumultuous decades now. What do you think was the hardest storm the industry had to weather during your career?

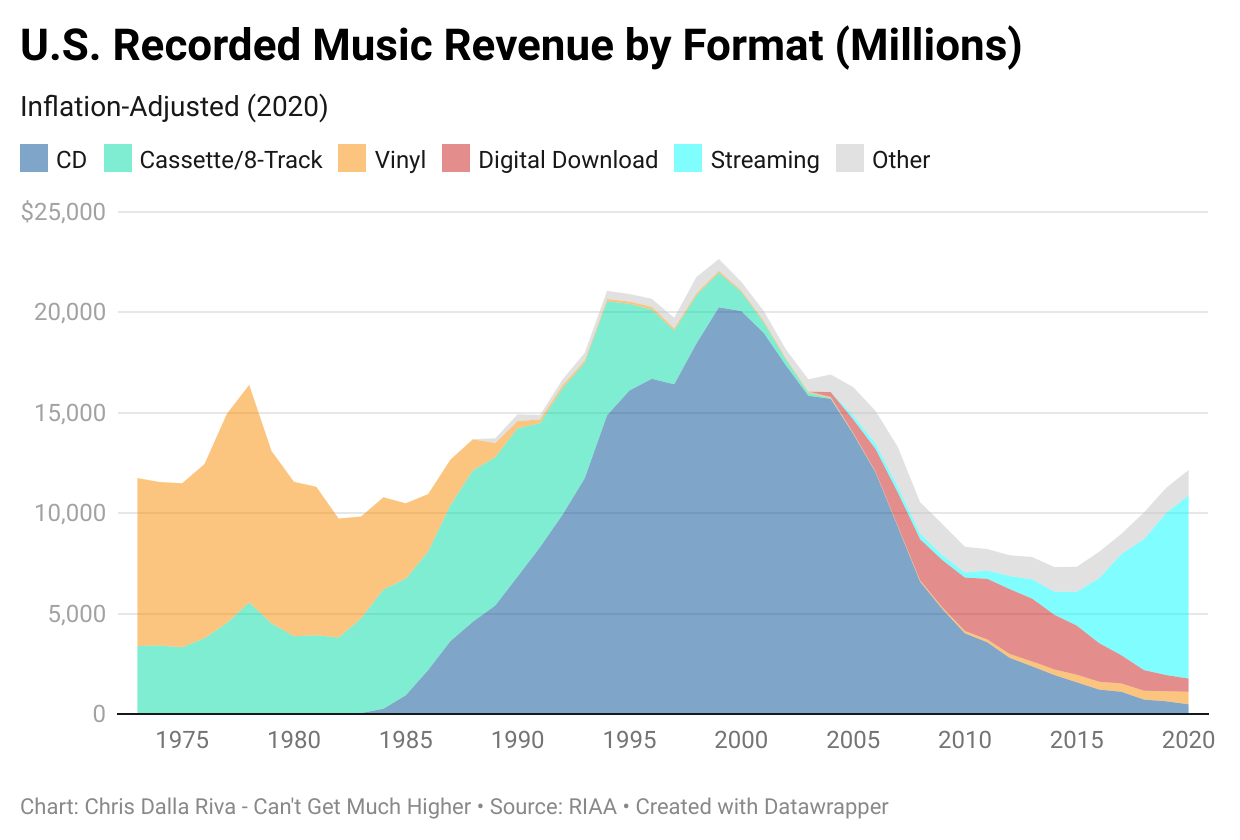

The premise of the book is that music is always the first to suffer from digital disruption and subsequently the first to recover. We saw that with piracy, and we're seeing that today with large-language AI models. The hardest pill for the industry to swallow in the 2000s was when they had to switch from fighting to embracing streaming. At that time, they were spending millions on litigation and losing billions in revenue. You can’t carry on like that. The war against piracy was ultimately unsustainable.

Do you think the music industry’s response to AI will ultimately be the same? Will there be tons of litigation and then an embrace?

I don't think it'll shake out in the same way as Napster. I don't think we're going to spend 10 years suffering because of this. But I can sense there will be divisions within labels about if they should choose to license to or sue AI companies.

I would like to note that there are some good actors in that space, though. Tracy Patrick Chan at Splash has been working with Roblox to allow kids to sing their own songs and if stars were to opt in — let's imagine Dua Lipa, Sabrina Carpenter — then through AI those stars will sing back that kid’s song. That’s very encouraging.

You left your position as Spotify’s Chief Economist to write Tarzan Economics. What made you think it was time to leave Spotify to write?

Teaching has always been a passion of mine. It’s something my father instilled in me when he taught me economics from the age of 11. Writing this book was a way for me to teach economics at scale. It’s been brewing in me from before I worked at PRS for Music and Spotify. As I was the lonely economist with a front row seat to disruption in the music industry, I knew that there was stuff I could teach others. Think about how the newspaper industry, banking sector, and government feel right now? ChatGPT is their Napster moment. Tarzan Economics was written for them as much as anybody in music.

Let’s talk about your time at Spotify. You were there for most of the company’s big moments. What do you think was a harder issue to tackle during your time there, technological issues or convincing the major labels to license their music for streaming?

The technology takes care of itself. The labels were a much bigger issue because they thought they’d be cannibalizing themselves by giving up analog dollars for digital dimes. They were afraid of having the one guy paying $50 per month on CDs start paying only $10 for a streaming subscription. We had to fight to convince them that that wasn’t the case.

When Spotify was initially negotiating with the labels, the average spend per person per year on CDs in the UK was £60. That was less than half of a yearly Spotify subscription. Even more important was the point that at that time, 60% of people spent nothing on music. These were people you couldn’t get into record shops. I started saying, “You can’t cannibalize zero.” From there, we had to convince the labels that streaming could turn some of those zeroes positive. That was a bigger mountain to climb than anything technological.

Was there any other data you presented to the labels that swayed them?

Canada was a big piece. In 2013, CD sales and digital downloads were both falling in all major markets, like the UK and US. But they were also falling in Canada even though Spotify wasn’t available there. In fact, there was no Spotify, no streaming, no Pandora and no iTunes radio. Labels wanted to point the finger at Spotify and blame us for cannibalizing downloads. But you couldn’t make that argument in Canada. Listeners had already moved on.

I spoke with your former colleague Glenn McDonald about a month ago. He posited that streaming will eventually make the music industry bigger than it was during the peak of the CD era. Do you agree with that?

You can try to quantify it. Let’s say in 2009 there were 100 million CD players in circulation. You needed people to have a CD player before you could sell them a CD. Compare that to how many people have smartphones today. 4 billion? Maybe more? With that fact alone, you can see that streaming revenues have the potential to eclipse peak CD revenues. The scale of the opportunity is just so much larger.

Before Spotify, you worked for PRS, a major collective management organization in Britain. In what ways did the issues you dealt with in the collective management world differ from the issues you dealt with in streaming?

For anyone who wants to work in the music business, collective management is a great place to start. Working at PRS, ASCAP, BMI, or any other major publisher gives you an inside look at how copyright really works. Having that knowledge puts you in a great position to work in any other part of the business.

Collection societies are also good training because the structure is so unique. Often, they are natural monopolies protected by the national treatment, structured as non-profits and governed by their membership. Very few entities in society tick all four of those boxes. That structure exposes you to a lot of interesting things. Collective bargaining is a good example. It doesn’t sound sexy, but collective bargaining underpins major sports and entertainment. My experience at PRS was a nice bridge to Spotify because Spotify’s value proposition is that you login and find every song you want. Publishers like PRS make that possible by offering blanket licenses for all of their music.

I want to talk about a few other hot button issues in music. First, let’s talk about pricing. Spotify and other streamers have been raising prices over the last few years. How high do you think a monthly subscription price will go before companies start seeing listeners cancel?