Artists Gone Too Soon: A Conversation with Jonathan Bernstein

After years of intense research, Jonathan Bernstein's biography of singer-songwriter Justin Townes Earle is finally here

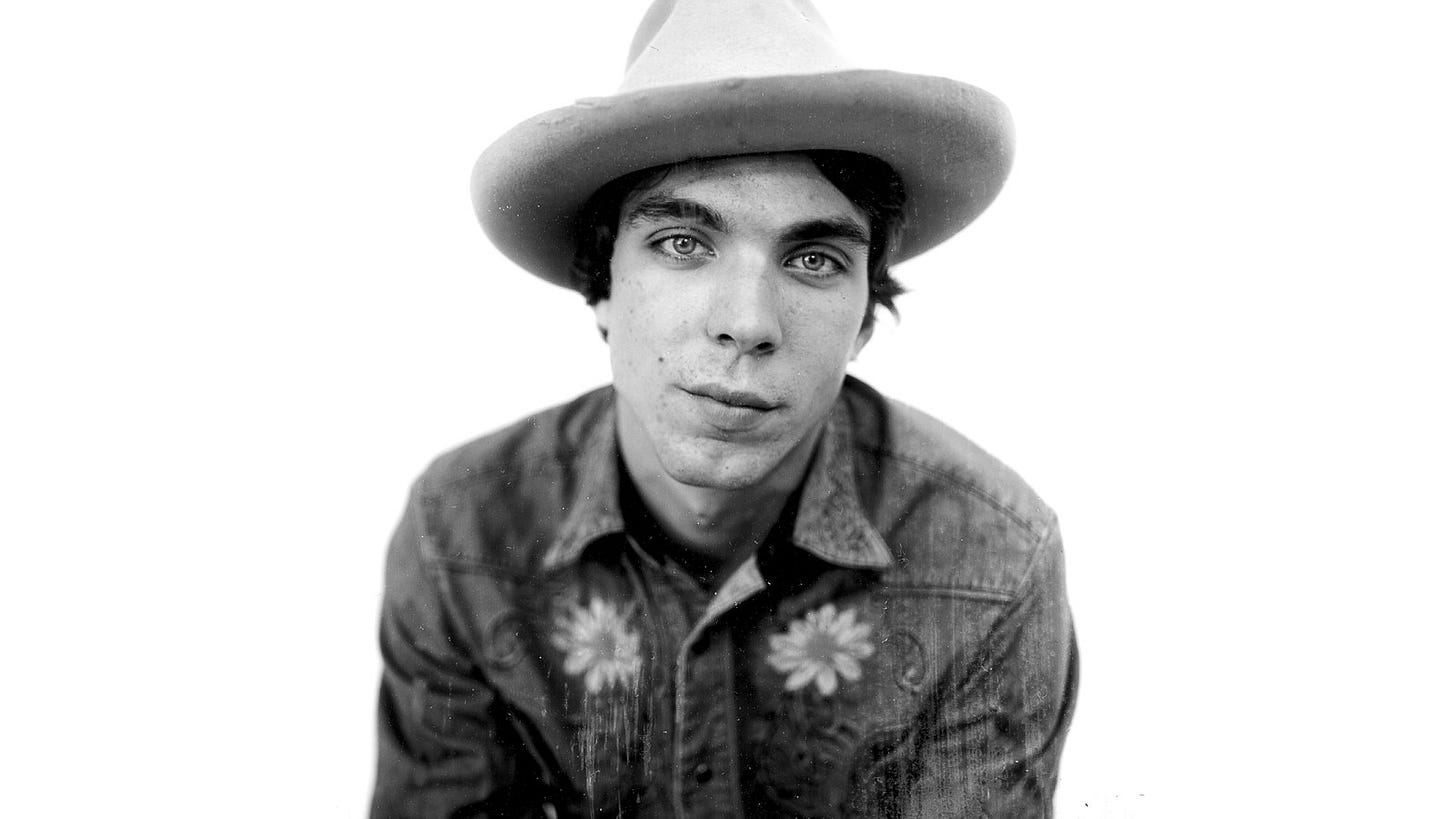

During his short life, Justin Townes Earle carved out a distinct career as a roving singer-songwriter. That’s not an easy thing to do when you’re the son of country legend, Steve Earle. But the younger Earle had the chops and the determination.

In his first book, What Do You Do When You’re Lonesome: The Authorized Biography of Justin Townes Earle, Jonathan Bernstein, a senior research editor at Rolling Stone, unravels the complex life of the late Justin Townes Earle, one of the most underrated songwriters of the 2000s. If you are a fan of Justin Townes Earle or roots music, you will love this book. But I think what’s most powerful about Bernstein’s writing is how he captures the archetypal contours of a life that will keep you reading whether you know the subject or not.

You open your book talking about “the myth,” or this idea that you must suffer to make great art. This is something that Justin Townes Earle seemed to believe. Do you believe in the myth?

I went into this book not wanting to glamorize or romanticize the suffering that Justin experienced in his life. This idea of the myth—that you must live this rock and roll life and sacrifice everything in pursuit of beauty and art—is complicated. In our culture, there is some acceptance of this idea. It’s a narrative that is used to market art. Justin is one of many examples of this narrative killing people.

At the outset, I wanted to write a book that would counterbalance that idea and perhaps rejected it outright. I’m not sure I achieved that, but as I went along, I realized that it’s not always completely black and white. It’s hard to tell a story like this and not glamorize it in any way. There’s a veneer of beauty just by telling the story.

I don’t think the book glamorized anything. If anything, it came across as a cautionary tale. What motivated you to want this to be the first book you wrote?

The short answer is that I was a huge fan of Justin Townes Earle. The longer answer is that after he died, I was assigned a story at Rolling Stone about him. They wanted me to report out what happened. It was my first big print feature for the magazine. I spent months on the story, interviewing so many people, including Justin’s widow Jenn Marie.

When the story came out in January 2021, I still had a hunger to learn more. I’d never written something so comprehensive. In writing it, I felt like there were threads of stories about Nashville and roots music and the 2000s, along with the main story of Justin’s life. I thought that all that had to be told.

By the end of the book, did you feel like you’d opened all those doors that were still left unopened when reporting the initial story for Rolling Stone?

I think the short, almost, existential answer to that question is no. I feel like the book was an almost magnified, drawn-out version of the article. I’ve never written a biography or anything like that before, and what I personally have learned is that while I did a ton of research, it was a humbling experience. The more I learned, the less I felt that I knew. There are just so many shades to a person.

It’s destabilizing to get to your 231st interview and have everything completely upturned. Justin was very mercurial and showed different sides to different sorts of people. In some ways, he was mysterious and private. In other ways, he was like an open book. If I had more years, I bet the book would be a little different.

Are you talking about a specific example with the 231st interview, or are you speaking generally?