The Darkside of Fandom: A Conversation with Monia Ali

Monia Ali was deeply devoted to One Direction until she was forced out of the fandom. Now, she chronicles how being a fan can be very toxic.

In 2019, Merriam-Webster added 640 new words to the dictionary. That’s not strange. They add new words every year. But one of those words got a bit more press coverage than the others: stan. Coined by Eminem in his 2000 song of the same name, Merriam-Webster defined the word in its respective nounal and verbal forms as a disparaging slang for an excessively devoted fan or exhibiting excessive fandom. In the years since its dictionary recognition, excessive fandom — or standom — has become even more common. And Monia Ali has been chronicling its rise.

Ali writes Fandom Exile, a newsletter about fandom in all its various shapes and sizes. Her knowledge comes from experience. She was deeply devoted to One Direction for a long time before being exiled by her fellow fans for disbelieving unfounded theories about the band getting back together. Over an hour, we spoke about the cultish toxicity of fandom, how fandom has changed in the last hundred years, and the insanity of the New York Times publishing an opinion piece suggesting that Taylor Swift is gay. If you enjoy our conversation, make sure to subscribe to Fandom Exile.

A Conversation with Monia Ali

The author biography for your newsletter opens up with a very arresting quote: “I was a fan, then I was a stan. I couldn’t tell the difference between the two until I was exiled from stan-dom.” What is the difference between being a fan and being a stan?

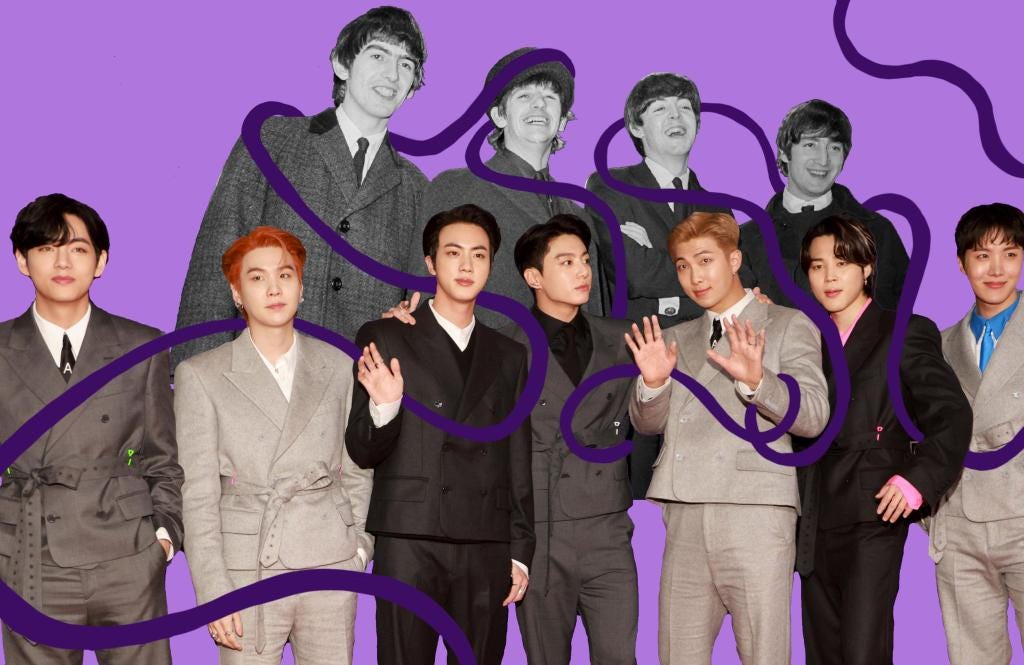

The industry definition of a stan is just whatever they consider to be a super fan. But then stans themselves have their own definitions. I recently saw a tweet by a BTS fan and they were basically saying, “Oh, you don't have to be streaming all the time and buying everything and going to every show. You’re still a fan if you just enjoy the music.” Then this stan came in and was like, “So, why are you even here? It’s not for BTS. It’s just for yourself.” In those communities, it’s not just about being a super fan. It’s about being an evangelist.

The idea of celebrity worship is nothing new. Do you think fandom today is different from, say, fandom of The Beatles in the 1960s or Elvis Presley in the 1950s or Frank Sinatra in the 1940s?

You can go back even further than that. You have Lisztomania in the 1840s. In the 1910s, Hollywood studios starting getting letters from fans not asking about movies but about the personal lives of actors. Because of that, you had magazines begin to cover the lives of those people. And a lot of those fan behaviors are similar to today.

When Gene Autry was in the 1940s, his fans set up a “postcard patrol” to try to keep him relevant during his time of service. Actually, I have a quote about this from Public Cowboy No. 1, Holly George-Warren’s biography about Autry: “The well-executed plan involved a card-writing campaign to various publications requesting articles on Sergeant Autry. Their constant stream of correspondence to key editors helped to keep Gene in the public eye. They also mailed cards to such radio programs as The Hit Parade requesting Gene Autry music.”

Do you think the only difference is that the internet exacerbated the fan phenomenon?

To a degree. It’s very human to be drawn to artists and performers. One of the differences today is that intense fandom is dependent on narratives and secret knowledge. Like you will frequently hear people talking about hints Taylor Swift is dropping about her new music and stuff like that.

Do you have any other examples of these narratives that fuel intense fandom?

Of course. There is this perception with BTS, or any boy band, that these guys aren’t just coworkers. They are brothers who will always support one another. But that’s not the case. It’s just a business. In the BTS subreddits, you see fans fracturing now that they are realizing that the band is actually broken up and that certain members will get more support from the industry than others in their solo careers. The same thing happened with me when I was part of One Direction standom.

It almost sounds like you’re describing a cult.

It is like a cult. In my experience with One Direction fandom, you had a ton of information control. You had people who ran these online forums exiling people if they didn’t agree with the popular narratives being put forth by fans. You become told what you had to think to stay in the group.

You’ve alluded to your standom experience a few times. Can you tell me a bit more about that?

I've been involved in fandom for as long as I can remember. So, joining a fandom was never really weird to me. It’s like a fun hobby that you can make friends through. But my One Direction fandom was different because it took over my life. It’s sort of embarrassing, but I think it’s important to share. Let me try to explain the intensity.

I’m a big movie fan. For a long time, I would try to watch 100 movies each year. But the first year I got really into One Direction, I only watched two movies. My entire Tumblr feed was only One Direction. I even ended up moving in with a fellow One Direction fan.

What drove that intensity?

There are these intense highs whenever news would drop about the band or one of its members. I literally don’t think I slept through an entire night at the height of my fandom. I’d just get too worried that I was going to miss news.

You can imagine how hard it was for me when I was kicked out of the fandom. I know the act of getting kicked out sounds weird. It’s not like I was paying to be part of this club. But it just became clear to me that the band wasn’t getting back together and most of the industry resources were being given to Harry Styles. The rest of the fandom did not agree with that narrative, so they sort of push me out as if I were doing something morally wrong.

You’re alluding to another thing that comes up in your author bio. You write that you “didn’t even come close to understanding the forces at work in both fandom and stan-dom until much, much later.” What do you mean by this? Are these musical forces? Economic? Technological?

Like I said, it became clear that the industry was putting more resources behind Harry Styles. That made you want to do even more for the other members of One Direction to prove that they should be given the same resources. But nothing a fan could do would change the way that labels and the music industry was investing in certain artists. Fans in those communities just think they have more power than they really do.

Do you have any specific examples of what you’re describing?

Sure. Like Louis Tomlinson would release a song, and these communities would have tons of fans call into radio stations requesting that they play his new song. And the station would be like, “Sorry. We can’t play that.” In our heads, we were confused. The song was out. But a song has to be serviced to the station. Fans have little power to make that happen.

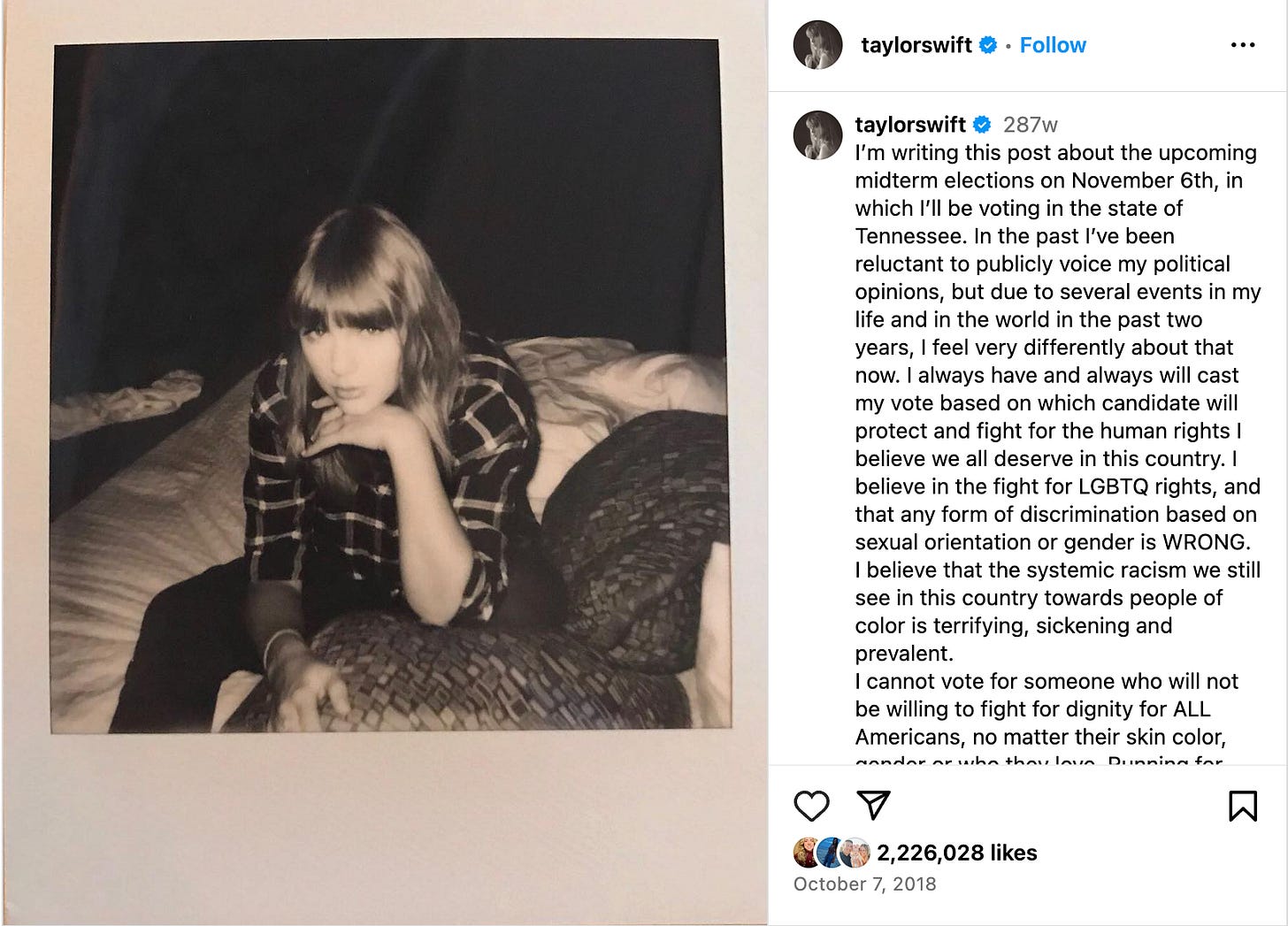

Another example is Taylor Swift endorsing politicians. The biggest fans feel like they need to evangelize the candidates that Taylor came out to support. But it’s not like everyone she’s endorsed has won. There’s just this disconnect between what stans think they can impact and what they can actually impact. You can’t just love an artist so much that it changes the world.

Over the last couple of decades, there has been a decline in religiousness in the western world. I’ve seen this idea put forth that even if people aren’t going to a church or a mosque or a temple that they always worship something. Some people worship work. Some worship sports. Do you think fandom is a way to replace the lack of a higher power in people’s lives?