The Life of a Critic: A Conversation with Wayne Robins

Critic Wayne Robins pops by for a chat about his long, varied career in the music business

If you enjoy this newsletter, consider ordering a copy of my debut book, Uncharted Territory: What Numbers Tell Us about the Biggest Hit Songs and Ourselves. It’s a data-driven history of popular music covering 1958 to 2025.

Today, I am talking with Wayne Robins, one of my favorite music critics around. Given that he’s written for most of the biggest music publications of the second half of the 20th century, I was of course familiar with the broad contours of Robins’ career. But as we talked about his afternoon sipping whiskey with Keith Richards, what Barry Manilow taught him about criticism, and how chefs are more similar to rockstars than you might think, I learned that there’s much more to his story than meets the eye. If you enjoy his thoughts, check out his newsletter Critical Conditions.

Right before this interview, I reread an older piece that you wrote about Beyoncé’s album Renaissance. At the top of the article, you mention some recent discourse around music criticism, specifically focusing on your disdain for the terms “poptimism” and “rockism.” What is your whole take on this brouhaha that critics are too nice these days?

“Poptimism” is an invented word that can’t be spoken in a colloquial English sentence, so I disavow it for writing about music. It’s not that critics are too nice. It’s that the outlets have disappeared, and witty, articulate critical arts writing has disappeared.

I worked the best part of my critical life writing for daily newspapers—mine was Newsday (1975-1995), once a Long Island monolith with 550,000 daily readers and over 600,000 on Sunday, and its short lived (1985-1995) city edition, New York Newsday. We had two or three critics on each arts beat: movies, TV, pop and rock music, classical music, ballet, and modern dance. Now, every newspaper is gutting their arts sections: The day we first spoke, a month or so ago, the Chicago Tribune had gotten rid of both of its longtime movie critics. The New York Times has done away mostly with daily concert reviews unless it’s Taylor Swift or someone of that stature.

The reason I posted the Beyoncé review was to show that one could express complex feelings about a record, clap back at the stans who just love everything that artist does, including the critics of the New York Times, who write about Beyoncé with a deference that would have once impossible. That deference is inherent in a word a phrase I never use: “The Boss” when speaking about Springsteen. Why? It sounds better in Spanish, as I was telling a Latino friend: “Yo no trabajo por el hombre.” I do not work for the man.

A shorter answer about “too nice” critics is that people don’t demand it, did not grow up reading smart critics whose wit could sting. You have to be a subtle writer to do that. And there’s too much out there to spend time on terrible debut albums, for example.

When you were working at Newsday, you established what was known as the “Manilow Rules.” Can you explain what those were?

When I started there in 1975, my editor, an experienced newspaper man named Joseph C. Koenenn told me something like, “You are not just the rock critic. You’re the pop music writer. You’re going to have to see a lot of shows that might not be your particular sweet spot. But you can’t go to a Barry Manilow show and decide you don’t look him because you would rather be seeing the Ramones that night. You have to go to a Manilow show and tell the reader if he is being the best Barry Manilow he can be that night.”

I put my head in the Manilow fans head and one night, my third or fourth Manilow concert, I thought he was off. Tired. The enthusiasm forced. And I noticed that the audience was unenthused too: They sat on their hands. The clapping was polite, but you could tell, they didn’t care as much as they usually did. So, when I wrote a kind of negative review, I said that: I wasn’t putting down Barry Manilow, I was saying that as Barry Manilow shows went, it just wasn’t as good. Because when he was “on” he was a great entertainer.

Before your time at Creem and Newsday, you worked at CBS Records. Tell me a bit about how you got that job and what it entailed.

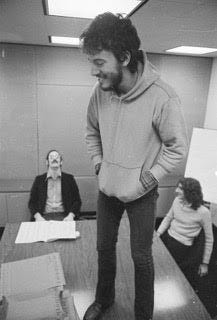

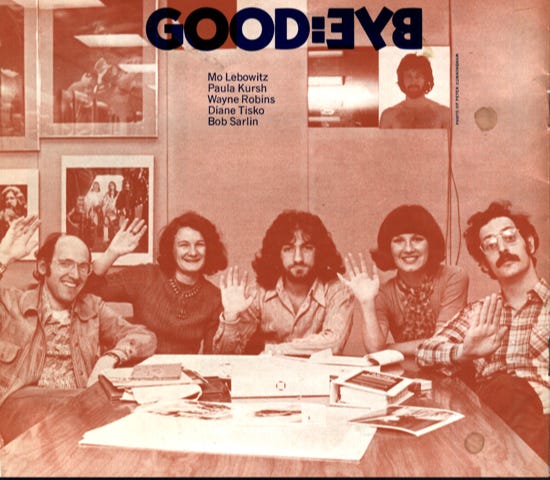

It was like a PhD in the music industry. I graduated in 1972 from the University of Colorado in Boulder, my third college in five years. I had already been published in Creem, the Village Voice, Rolling Stone, Fusion, and alternative publications in every city. But no critic I had met or spoken to knew how the big-time record business really worked. I got hired because a guy named Bob Sarlin, who was a friend of my girlfriend at Bard (an earlier school) had become a mentor. I respected him because he had been a newspaper reporter, which was what I really wanted to be. Bob had already done PR. He had been the PR guy for Don McLean’s “American Pie,” which had become a huge phenomenon. So, CBS Records asked him to put out a twice a month magazine called Playback, an answer to Warner’s very popular house magazine Circular.

He called me that summer of 1972. I had no ambition and no clue, I thought I was going to move back to Boulder to write for the off-campus Colorado Daily, which paid a nominal salary. But he hired me to be his number two guy. Clive Davis was still in charge but got fired halfway through our two-year run, so we were privy to how major corporate decisions were made. And we’d go to the weekly marketing, sales, A&R, singles and albums radio promotion meetings. It gave me a leg up on other critics, because I knew how the sausage was made. Example: Why were we releasing such a shitty album by new artist XYZ? Because they were managed by the powerful manager who was given a small label imprint of his own because his artist ABC had sold ten million copies. Just owed the guy a favor. Also, it didn’t matter that it sold zero minus one: It was a legitimate tax loss to be written off. Failure as a tax deduction. Who knew?

You did spend the bulk of your career as a critic at Newsday, though. Can you tell me a bit about how you ended up there and what your top 3 most surreal memories were as a critic there? I read once that you spent a day drinking whiskey with Keith Richards while he was working on the Chuck Berry documentary Hail! Hail! Rock and Roll.

My two most influential people in rock criticism, Robert Christgau and Dave Marsh, had both served as Newsday rock critics. Like I said, it was the most big-time suburban newspaper in the country, winning Pulitzers, bureaus all over the world. Christgau knew I had grown up on Long Island. He was Newsday’s first rock critic. Then Marsh followed him. When Christgau got his dream job to become the music editor of the Village Voice, the most influential arts and politics weekly in the country, in 1974, I became a regular contributor because CBS decided they couldn’t afford Playback anymore.

Marsh left Creem at some point earlier to replace Christgau at Newsday when he went on leave. When Marsh left to go to Rolling Stone and fame and fortune as Springsteen’s first biographer, they both recommended me for the job. So when I left Creem after six months (I was editor in chief spring through fall of 1975), I more or less had the job waiting. And because I was from Long Island, I knew the geography, and social stratas and stuff, and made sure I used phrases like “from Manhasset to Montauk” to show the editors I knew the area. I was like a prodigal son returning home.

So yeah, interviewing Keith Richards for Hail! Hail! Rock and Roll, it was Keith and I in his office in New York, drinking a bottle of Maker’s Mark. He didn’t have anything else scheduled that afternoon! So we just kept drinking and talking, and at one point he said: “I’m not done mixing the soundtrack. Do you wanna hear some rough cuts? So he puts on a cassette, we both stand up, and we play air guitar along with the Chuck Berry songs.

The other good stuff included three weeks on the road covering Billy Joel’s 1987 tour of Russia. It wasn’t a junket. I handed in a $10,000 expense account for that trip. I went to L.A. at least once a year to interview celebrities. If I needed to file something, I used the L.A. Times newsroom, since Times-Mirror, the LA paper’s owner, owned Newsday then, and our former much-respected editor, Dave Laventhol, had been brought west to be publisher of the LA Times.

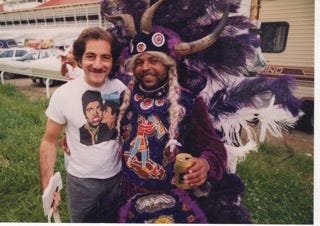

One more great trip was interviewing Clint Eastwood in New Orleans. There had been a big country radio junket to promote his movie Bronco Billy in June 1980. There was also a country soundtrack with Merle Haggard and others. So the label called me to see if I wanted to go. I told them we couldn’t take free trips, but Newsday would pay my way if I was promised some one-on-one time with Clint Eastwood.

We negotiated about 20 minutes. Everything else was roundtables with country DJs, Clint would talk to a table of ten or so at the luncheon at a fancy French Quarter restaurant, then move on. When he was introduced to me, he said, “you’re the guy whose paper paid your way. Wait for me to finish this.” We only had a couple of minutes that afternoon, the staff was turning the tables for the dinner service. I asked a good question, wish I remember what it was, but he didn’t finish answering it, so he invited me to his hotel suite the next morning when the junket obligations were over. We talked over beer and oysters for at least three hours.

Across those decades, music and criticism evolved dramatically. Can you tell me what had changed the most from writing your first review in the late 1960s to when you took the Newsday buy out in the mid-1990s?

At first I wanted to be a gonzo journalist, like Hunter S. Thompson. My first published review in 1969 of the Rolling Stones, B.B. King, Ike and Tina Turner, for the weekly Berkeley Barb during my “gap year” between Bard and the Univ. of Colorado, was written under the influence of some very powerful weed and equally strong meth. The Creem ethos was kind of anything goes, as everyone wanted to write like Lester Bangs.

That was fun, and I wrote there regularly from wherever I was from 1971 (Boulder) through the CBS years (New York), until I became the editor in 1975. When I was hired, though, it was to help make the magazine more professional. And like I implied, my heroes were not rock critics, though I was influenced enormously by Lester Bangs, Greil Marcus, Robert Christgau, and Dave Marsh. But I really looked up to the great 20th century newspaper columnists like Pete Hamill and Jimmy Breslin.

Also, when I started at Newsday, I was still channeling Christgau a bit, and my late brother David, who was no dummy, took me down a notch when he said, “I really enjoy what you write, I just wish I didn’t have to look for a dictionary every sentence.” Thanks to him, I found my own writing voice was much like my speaking voice. And it’s been that way ever since.

Though you spent much of your career writing about music, you also had long forays into writing about food and politics. Can you tell me how that came about? Furthermore, do you think your history in writing about music informed any of that writing.

My first wife, who was a star news reporter at Newsday, and I were big food and wine fans. I was also a functioning alcoholic for much of my life, but I always framed it as a “food and wine guy.” In 1994, I was burned out on music, especially after Kurt Cobain’s suicide. So I asked the food editor, a smart and elegant woman named Irene Sax, if I could join her department. She had a dozen reporters, but all were women except for the restaurant critic. I proposed I could bring a different, fresh voice to the food section. The Super Bowl was coming up, and she was sick of chili recipes, so I said, “How about hiring me? I’ll interview the great chefs of New York and Long Island about their dream Super Bowl parties.” She loved the idea and the execution, so I switched beats.

I also got to write about “the best vodka martini in Manhattan” on my expense account, so I spent about three weeks leaving the office early and hitting every famous bar, from the Four Seasons to the 21 Club, interviewing cocktail specialists, and drinking martinis. My whole career I could drink because nobody expected the rock critic or the “martini specialist” to show up early after a night’s work.

But chef’s were just like rock stars. In fact, in the New York of the 1980s and 1990s, they were the “rock stars.” And still are. I hung out at a book party once with Anthony Bourdain. It was like 95 degrees on a hot summer day in the NY meatpacking district, and I remember the women eyeing him like he was Mick Jagger. And instead of gin and tonic, he ordered single malt whiskey, neat. I liked that in a drinker.

I had no interest in politics. I wanted to be a “media pundit” when I worked (from 2002-2004) for Editor & Publisher, the weekly trade magazine of the already dying newspaper industry. They let me write op-eds, sometimes even when I disagreed with the magazine’s own editorial.

When Billboard was celebrating the 25th anniversary of Paul’s Boutique, they published your review from when it was released: “The idea of a mature Beastie Boys album would seem to be an oxymoron. And the notion of listening to a rap record for its music ought to be a contradiction. But Paul’s Boutique, the Beastie Boys’ second album, is strangely, unexpectedly, a grown-up audio delight.” This review has aged like fine wine. Are there any albums you reviewed over the years that you panned at first but have come to like? What changed your opinion?

The albums and concerts I regret panning were The Smiths, which I disliked then but love now, and I missed the boat on bands like Depeche Mode. I just didn’t understand the British synth-rock scene as a guitar-rock boomer.

The “Manilow Rule” also applied to the band Rush. I reviewed a show without doing my homework, only knew a few songs, and wrote a very unfair review. The next time they came around, I spent a week “working at home” listening to their catalog, so I knew what songs they were performing, and enjoyed the show. I felt I owed it to my readers to be fair. Teenagers used to come home from school and write me letters about my reviews, and when I was wrong, they let me know it.

One of the things that I admire about many of the writers of your generation, like Greil Marcus and Robert Christgau, is that you continue writing. All these years later, what keeps you motivated?

“Some people write to live; others live to write.” I suspect we are all the latter. What else would we do, play golf?

Later in life, you spent much time teaching. How did you get into that?

I got an M.A. in Cultural Reporting and Criticism in 1999 from the NYU graduate school of journalism, created by the first great woman rock critic Ellen Willis. I taught two semesters of critical writing at NYU but didn’t like it. It was when the drinking was really catching up with me.

In 2013, I was copy editing at little better than minimum wage for a Queens weekly, and one of the reporters was a St. John’s University journalism grad. He suggested me to the department chair for a last minute replacement for an arts criticism course, and I got the job. Then the Engish departent chair turned out to be a fan of my Creem stuff, and he asked me to teach a section of his music criticism course. The courses kept coming.

At first I thought I was a writer doing part time teaching. Somewhere in my third or fourth year of teaching two courses every semester, I realized I was a teacher who wrote on the side. I got promoted to full professor, won lots of awards that I didn’t apply for, and got tremendous joy passing on the lessons I learned as a journalist and person in recovery to my students, until I decided to stop at the end of the semester May 2024. Now I’ve got grandkids to care for, and my Substack, now in its fifth year and still growing.

What can people look forward to from Wayne Robins in the next few months?

I just got asked to join a storytelling-as-entertainment group, “(almost) True Stories.” The leader invited me after reading my storytelling on Substack, which is what I do. In fact, the first gig is Sunday afternoon, in Roslyn, Long Island. The next is October 11 in Port Jefferson, Long Island. It’s a paying gig, so I’m kinda in show biz now!

Want more from Wayne Robins? Check out his incredible music newsletter, Critical Conditions.

Want more from Chris Dalla Riva? Consider pre-ordering a copy of his book Uncharted Territory: What Numbers Tell Us about the Biggest Hit Songs and Ourselves.

The Professor is one of my faves on here! Thanks for pulling the curtain back and letting him share his story with everyone.

Great interview. What a career Wayne's had.