The Makings of a Hitmaking Warrior: A Conversation with Holly Knight

Holly Knight broke barriers as a woman writing hit songs in the 1980s. Now, she's telling her story in a new memoir.

Holly Knight is a trailblazer. While it is still rare for women to find success exclusively as songwriters, it was even rarer in the 1980s. During that decade, Knight became one of the most sought after hitmakers in the industry, writing everything from Pat Benatar’s “Love is a Battlefield” to Tina Turner’s “The Best” to Patty Smyth’s “The Warrior”.

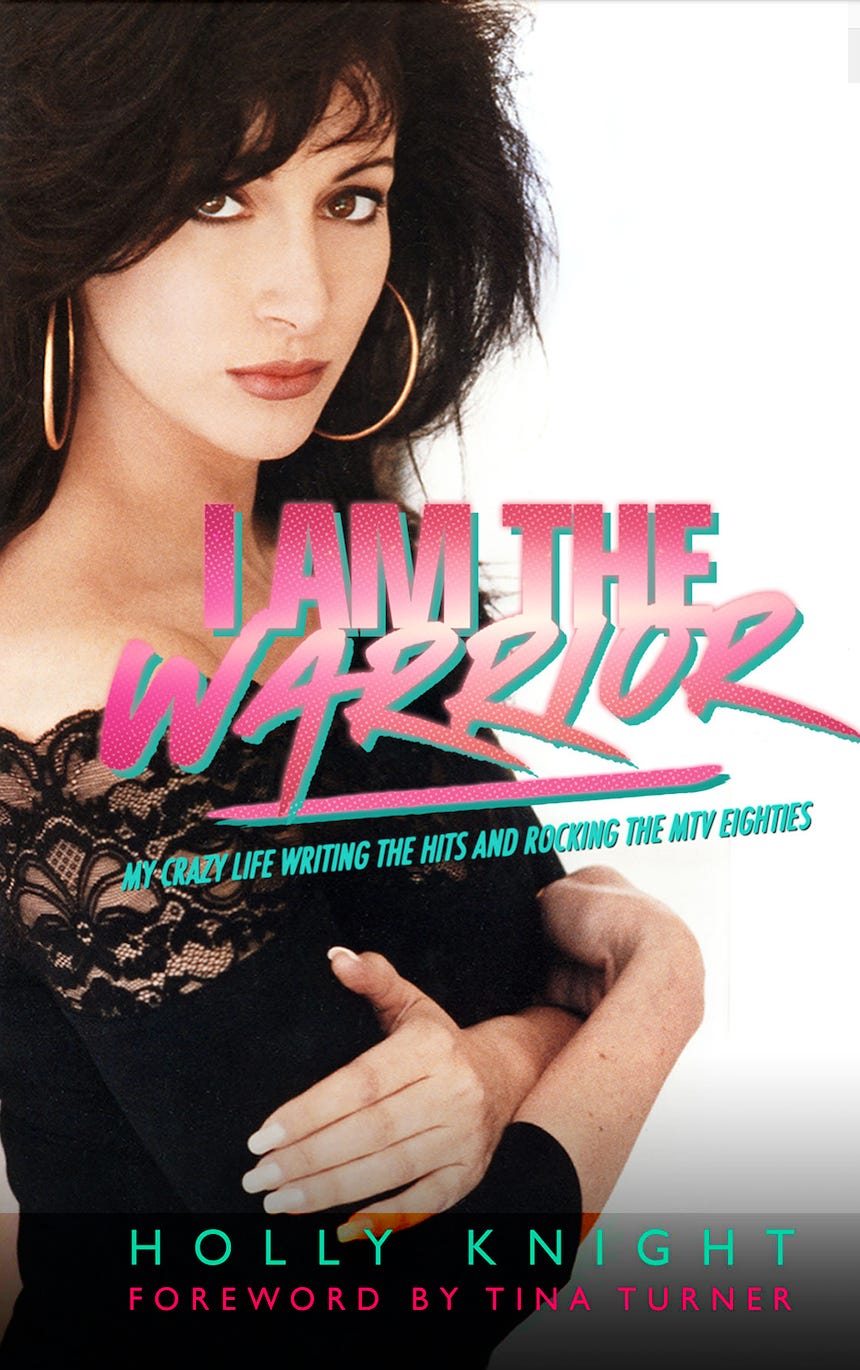

Last week, the two of us sat down for an hour to talk about her upbringing, how she manages to capture such drama in her songs, and her recent memoir, I Am the Warrior: My Crazy Life Writing the Hits and Rocking the MTV Eighties, available now via Permuted Press.

A Conversation with Holly Knight

Before you were a full-time songwriter, you were in a band called Spider. Two songs on Spider’s second album - “Change” and “Better Be Good to Me” - became hits for other artists, namely, John Waite and Tina Turner. Why do you think something like “Better Be Good to Me” ended up being a much bigger song for Tina Turner than it ever was for Spider?

“Better Be Good to Me” was a single on Tina Turner’s album Private Dancer. That was one of the biggest albums of 1984. In fact, Tina was nominated for multiple Grammys that year, including Album of the Year.

The Spider version wasn’t promoted because of a payola scandal that exploded in the music business at the time. Everybody that had released records around then basically lost any chance of promoting them or doing anything with them.

As I was listening to your discography the one thing that struck me is your music’s intensity. From Aerosmith’s “Rag Doll” to Bon Jovi’s “Stick to Your Guns” to Patty Smyth's “The Warrior”, your songs are like a punch to the chest. Why do you think you're so good at capturing that intensity in your compositions?

I remember one interviewer asked me why all my songs were about fighting. I kind of looked at him confused and was like, “No they're not.” He responded, “No, they are. That's not a bad thing, though. It's very compelling.”

Since then, I’ve done some soul searching and come to the realization that he was mostly right. The songs weren’t about fighting with people, though. They were about fighting something external. Ultimately, I think you write what you know or whatever you create in your mind.

In your book, you talk extensively about your upbringing. There is this dichotomy that you make very clear where you had supportive grandparents, along with a father coming to see you perform in literally every club before you hit it big, but your relationship with your mother was tumultuous. She pushed you to learn piano, but was also physically and emotionally abusive toward you. Do you think part of that intensity in your songs is driven by your childhood?

Oh, absolutely. I think the first ten years of a person’s life are the blueprint for the rest of it. Honestly, you spend most of your life trying to fix any issues from that first decade. There was a lot of turmoil and struggle during my formative years. That’s okay, though. Survivors have the best stories.

I also noticed the people who sing your songs often have very distinct, intense voices. Tina Turner and Pat Benatar are great examples. But even something that isn’t as intense, like “Love Touch”, you have someone like Rod Stewart singing. His voice is as evocative as anybody else’s. Do you think only certain vocalists can handle the grandeur and drama of your songs?

I think that's the case with certain songs, but there are others where that's not the case at all. Some songs are more dependent on attitude. If I’m working with someone who doesn’t have a huge range, I will deliberately write something that is more linear and compact. There are other artists where I don’t have to do that. I knew Pat Benatar had an incredible range, so when I wrote “Invincible” for her, I composed a vocal that moved around a lot. I knew she could handle it.

There's also like this cinematic quality to many of your songs. “Love is a Battlefield”, which Pat Benatar also sang, is great example of that. There’s a good deal of spoken dialogue in the music video, and it works because the song feels like a movie. You can almost see it. Do you actively think about music visually? If so, do you think that helped you find success in the 1980s when MTV and music videos were so important?

To this day when I'm writing a song, I can see the video as the song is unfolding. Even if the video never gets made, it’s in my head. I just love drama and passion. Plus, I’m a bit of a movie buff.

I think a lot of the drama in my songs comes from my dysfunctional family. When you grow up like that, you feel things hard, you love hard, you win hard, and you lose hard. Everything is emotional.

Your songs have also been licensed for tons of movies and television shows, so filmmakers definitely see that cinematic quality of your songs. “One for the Living” was in Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome. “I Can’t Untie You From Me” was in Thelma and Louise. “The Best” was in Schitt’s Creek. I could go on and on. Are you careful about where you license your songs?

I've said no maybe once or twice in my career. Other than that, I’m pretty open to people using my songs. “The Best” was actually in Pringles commercial in the Super Bowl last year. It was kind of silly, but it was the Super Bowl, so I let them do it.

I've been just incredibly lucky with licensing because everything is harder these days. I really feel for people starting out now that are trying to carve out a career in songwriting. I think there are a lot of things going on that really need to be changed for songwriters to survive.

What do you think needs to be changed?

For many streaming services, you get locked into a big blanket license instead of getting paid for the actual usage of your songs. So, there’s less money for songwriters to get paid for their services. Also, it’s hard to find writing credits on any streaming services. Credits listed on physical albums used to be like a business card for me.

Songwriters also don't have a union, so we can’t strike like screenwriters or car manufacturers do. Because of that, we often get a raw deal. Most songwriters work on spec, meaning that if your songs get made, you'll make some money. If they don’t, you get nothing. Songwriters don’t get paid upfront like studio engineers do. Top engineers might make $2,000 to $3,000 per day.

I was listening to an interview you did with Eddie Trunk, and you said that at that point “The Best” generates like 80% of your earnings. Is that true? That seems crazy given all the other huge songs you worked on.

It’s true. It's just been licensed so many times. There are other songs that have started getting licensed quite a bit, so maybe that's changing. But that’s the lion's share right now.

What is it about that song that still resonates? I know when Tina Turner’s version came out it only reached number 15 on the Hot 100. That’s no small feat, but you also charted songs much higher than that.