The Slop Problem is Worse Than You Think

AI can be used for good, but a lot of people are doing the opposite

Today, we are going to be talking about slop, a breed of AI-generated content taking over the internet. In an effort to fight against the perils of slop, I like to recommend great newsletters by great humans from time to time. If you’re not already familiar with it, I strongly recommend you check out Daniel Parris’s Stat Significant. Stat Significant is a free weekly newsletter featuring data-centric essays about movies, music, TV, and more.

If you like this newsletter, you’re sure to like Stat Significant. They’ve dug into questions about when we stop finding new music, the best television finales, movies that popularized baby names, and so much more.

The Slop Problem is Worse Than You Think

By Chris Dalla Riva

If you’ve been to a book store in the last few decades, you’ve likely seen entire shelves lined with books by Danielle Steel. There are two reasons for this. First, Danielle Steele is wildly successful. By some counts, she’s sold more books than anybody outside of William Shakespeare and Agatha Christie.

But lots of sales aren’t enough to line entire bookcases. Danielle Steele is also wildly prolific. Since the publication of her first novel in 1973, Steele has published over 200 books. In 2025 alone, she released eight.

That’s a lot of books. Even so, Danielle Steele has nothing on Bill Johns. According to his Amazon author profile, Johns published his first book a year ago. Since then, he’s put out another 330 volumes! And he’ll touch any topic. College sports. Chinese alcohol. Blues music. American history. He’s not only prolific. He’s also a polymath.

And he probably doesn’t exist.

Okay, maybe there is a man named Bill Johns out there somewhere. I can pair his author headshot with a LinkedIn profile, and the company listed on that profile has a website. (I reached out and have not heard back.) But there is no way that someone sat down and wrote these books attached to his name. When you enter the world of Bill Johns, you have entered the world of slop.

As artificial intelligence tools have proliferated over the last few years, the term “slop” has come into vogue. Search traffic for the term has quadrupled. Every publication from CNET to The Wall Street Journal has also been writing about it. But what exactly is it?

When Merriam-Webster named “slop” its word of the year in 2025, they defined it as “digital content of low quality that is produced usually in quantity by means of artificial intelligence.” That definition captures the Bill Johns literary universe. But I don’t think it captures the nuance of slop.

In his recent essay “notes on slop,” friend of the newsletter Adam Aleksic gets at the concept a bit more precisely. “Slop is form without content,” he writes. “[It] is intended to optimize for mass consumption … Whether slop actually succeeds is irrelevant: the intent is for it to be seen and heard, at the expense of meaningful communication.”

By this definition, “slop” is not new. Each day, for example, The New York Times has to fill up a newspaper with stories. Because there is less to say on certain days than others, the pages will occasionally be taken up by some analog slop. These columns respect the form of a news story without saying much.

Aleksic notes some other forms of slop that we’re all familiar with from the pre-AI world: “Hallmark movies are slop for feel-good holiday entertainment; junk mail is slop for postal advertising.”

So, if slop is not new, then what is the problem with AI-generated slop? Is Bill Johns cranking out books really that much different than television networks filling the airwaves with silly soap operas? Yes. In fact, I think it’s different enough where using the word “slop” to describe both phenomena isn’t accurate. While “slop” captures the former, the latter is better described as “filler.” Let’s pick apart how these two things differ.

#1 Filler Requires Humans. Slop Doesn’t.

It almost goes without saying, but slop is fundamentally different than filler because it requires very little human input. Even the crappiest of television movies will have many minutes of credits at the end. Slop doesn’t necessitate or require crediting in the same way.

#2 Filler Takes Up Space. Slop Defrauds and Deceives.

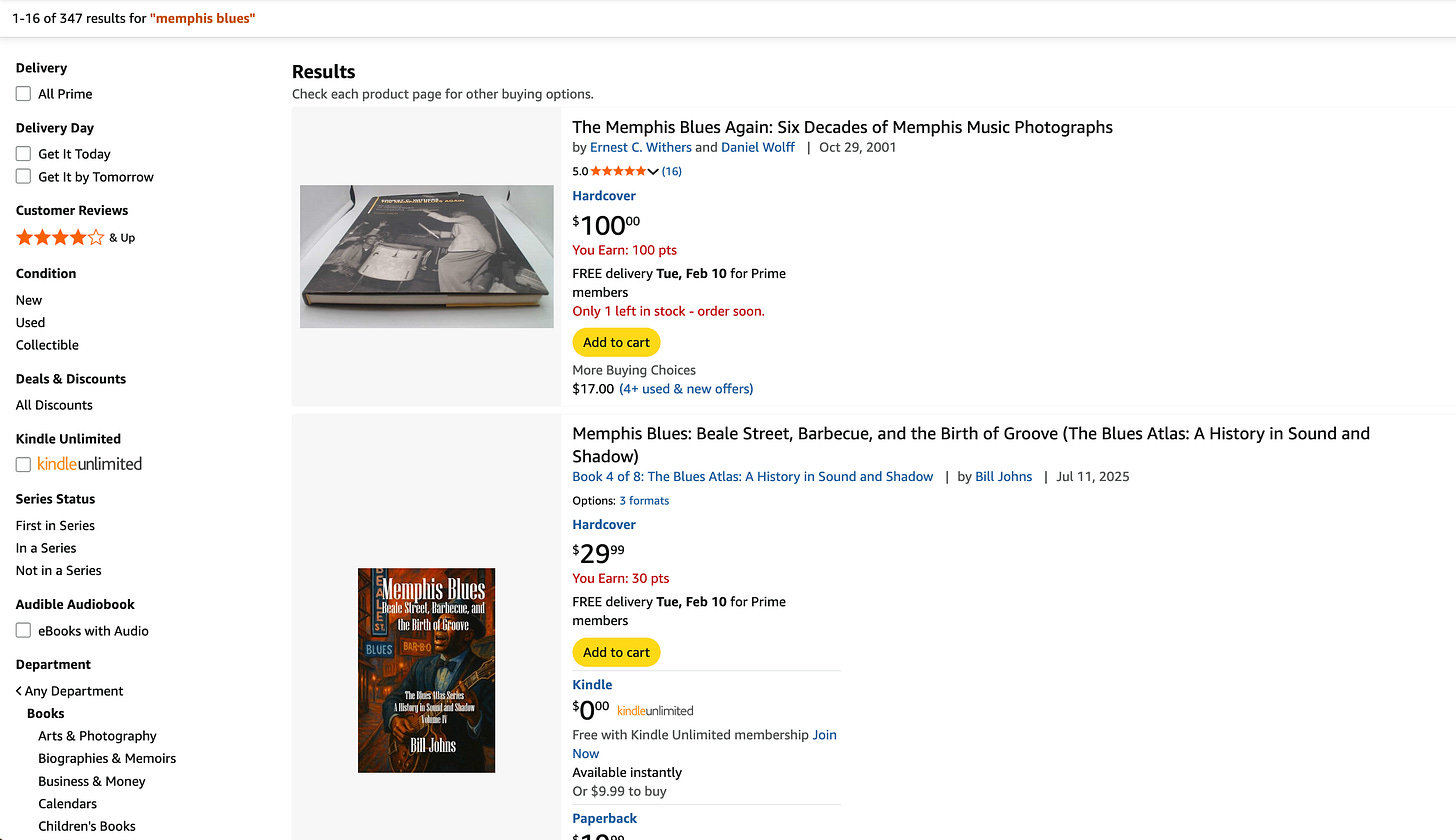

If we think about our friend Bill Johns for another moment, you may wonder why he—or anybody—would want to use AI to generate hundreds of books. The Memphis blues can teach us why.

If you go on Amazon and search for books about the Memphis Blues, the first result will be The Memphis Blues Again: Six Decades of Memphis Music Photographs by Ernest C. Withers and Daniel Wolff. The second result will be Memphis Blues: Beale Street, Barbecue, and the Birth of Groove by—you guessed it—Bill Johns. In other words, if you are trying to learn about something, you might end up accidentally lining the pockets of Bill Johns.

These scams are literally everywhere. And they are a huge problem. Not only do they confuse people, but they siphon money away from genuine artists. Recently, John Strohm wrote a tremendous piece about how the proliferation of AI-generated tracks across streaming services dilute the share of royalties going to genuine artists. Anyone writing a book about the Memphis blues is dealing with the same issue because of Bill Johns.

#3 Filler is Limited. Slop Scales.

Of course, scams are nothing new. (You can read about them—I kid you not—in the book The Confidence Game: Swindlers, Grifters, and the Architecture of Trust by Bill Johns.) But AI allows these scams to proliferate at a scale unseen in history. If I can generate an endless stream of video, audio, and text at the click of a button, it will eventually overwhelm any human-generated content on the internet.

Music streaming services are already dealing with this. Before AI tools were even available, we were seeing more releases in the matter of a week than we did across entire decades of the 20th century. Unless incentives change, I see every streaming service—and the entire internet, for that matter—turning into a pool of AI that we must sift through.

If you’ve read this newsletter long enough, you’ll know that I am not against AI generally. We are going to live in a world where these tools are used in some capacity across the music universe.

There are many ways the usage of those tools can go, though. They can be used to turn the digital world into an endless flow of scams, or they can be used to invigorate artists creatively in the same way that scores of earlier technologies have. It’s up to us to decide.

A New One

"Matter of Taste" by Tyler Ballgame

2026 - Indie Rock

The press for Tyler Ballgame’s debut album—For The First Time, Again—states that after struggling with depression, he went through a spiritual awakening that spawned his songs. On “A Matter of Trust,” a song steeped in aesthetics of the 1960s and 1970s, Ballgame sounds like a man possessed. When he growls “Baby, give your love to me” on the chorus of the track, you likewise feel your spirit being awakened.

An Old One

"Fascinating Rhythm" by Ella Fitzgerald

1959 - Swing

I’ve recently been reading Alex Ross’s excellent book The Rest Is Noise: Listening to the 20th Century. Ostensibly about classical music in the 1900s, the book has introduced me to so many compositions across genre. One of the most exciting has been “Fascinating Rhythm” by George and Ira Gershwin. Here’s how Ross describes the piece:

“Fascinating Rhythm” is a study in aural sleight of hand. Over a foursquare beat, the melody unfolds in three helter-skelter phrases, each made up of six eighth notes plus an eighth-note rest. The fact that each phrase falls one eighth note short of a complete bar means that the vocal keeps slipping ahead of the main beat; four extra pulses are needed to make up the difference.

While this rhythmic oddness would lead to trouble in less capable hands, the Gershwins make it feel like that’s how every song is supposed to sound, the pulse gently pushing and pulling you along. Naturally, Ella Fitzgerald handles this rhythmic funkiness with aplomb.

Thanks for reading. If you enjoy my work, please consider ordering a copy of my forthcoming book Uncharted Territory: What Numbers Tell Us about the Biggest Hit Songs and Ourselves. It’s a data-driven history of popular music that follows my journey listening to every number one hit from 1958 to 2025.

"The Slop Problem: AI, Filler, and Barbecue"-Bill Johns

Out Now!

Fantastic piece on the slop epidemic. The distinction between filler and slop really nails it because filler atleast required human labor creating some friction. What's wild is how the economic incentives are basically designed to reward this stuff since platforms dont care about quality just engagement metrics. Once we hit a tipping point where algorithmic curation can't tell the differnce between real and generated content the whole ecosystem collapses.