The Worst Day to Die

Or, complaining about a matter we don't have a ton of say in

Welcome to Can’t Get Much Higher, the internet’s favorite place to talk music and data. Today’s newsletter is about celebrities and inconvenient days to die. I promise it’s not as depressing as it sounds.

If you enjoy this newsletter, consider ordering a copy of my debut book, Uncharted Territory: What Numbers Tell Us about the Biggest Hit Songs and Ourselves. It’s a data-driven history of popular music covering 1958 to 2025 that The Economist called “entertaining,” and a hit songwriter said gave him “new ways to think about how I approach my own writing.”

The Worst Day to Die

By Chris Dalla Riva

I recently came across this fascinating passage in Alex Ross’s book The Rest is Noise: Listening to the 20th Century:

The long-awaited announcement [of Stalin’s death] was made on the morning of March 6, 1953. Moscow promptly dissolved into chaos: thousands of people swarmed around the Hall of Columns, where Stalin’s corpse was on view, and several hundred were trampled to death. So momentous was the news that Pravda [Soviet state newspaper] did not bother to report for another five days the fact that Sergei Prokofiev had also passed away. Sviatoslav Richter heard the news of Prokofiev’s death while flying back to Moscow to perform at Stalin’s funeral; he was the only passenger on a plane filled with wreaths.

About thirty people showed up to bid Prokofiev farewell. The Beethoven Quartet was instructed to play Tchaikovsky, although Prokofiev never liked Tchaikovsky; the quartet then disappeared into the mob to play the same music for Stalin. The hearse was not allowed near Prokofiev’s house, so the coffin had to be moved by hand, through and around streets that were blocked by crowds and tanks. As the masses moved toward the Hall of Columns along one avenue, Prokofiev’s body carried in the opposite direction down an empty street.

I won’t claim that there is a good day to die. But if you want people to celebrate your life, there are better days than others. Sergei Prokofiev got a bad day. One of the great composers of the 20th century, he ended up a footnote in the news because Soviet leader Joseph Stalin also died.

Prokofiev is not the only person to suffer this fate. Barely a few days after I read that passage in The Rest is Noise, I was meeting up with some writers in Brooklyn, and someone happened to bring up the fact that actress Farrah Fawcett died the same day as Michael Jackson.

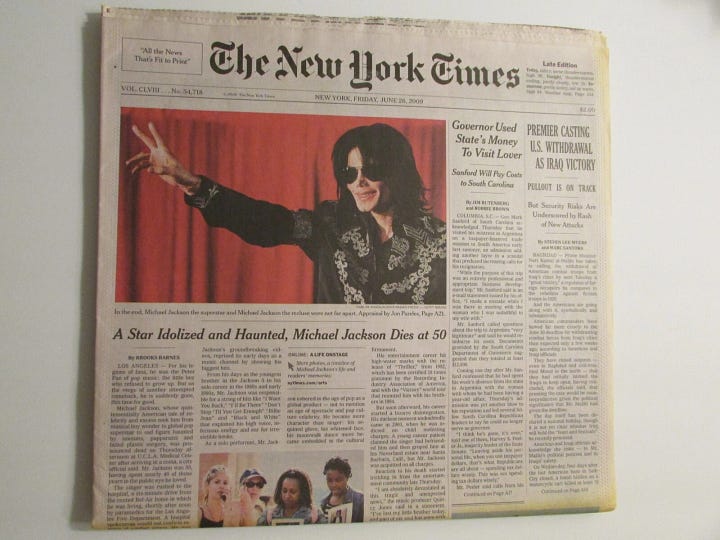

Fawcett was a major star, but Jackson took up headlines that day. His death was the top story in The New York Times. Fawcett’s death did make the cover, albeit on the bottom is significantly smaller text.

This got me wondering if there was an even more extreme example of this phenomenon. Was there a day with an even bigger celebrity death, one that would have dominated the news, totally overshadowed by someone even larger passing? I decided to take a look.

Die Another Day

Last week, I used a massive dataset of notable people to figure out which historical figure is mentioned most often in hit songs. Since that dataset also listed birth and death dates for those tens of thousands of notable individuals, I figured I could use it to answer this week’s query.

My process here was pretty simple. The dataset contains a notability score for each individual based on five criteria. Barack Obama and Donald Trump, for example, are the most notable individuals. William Shakespeare is number 8. Leo Tolstoy is 92. John Stamos is 6,871.

For each person in the database, I took the ratio of their notability score to the score of the most notable person that they shared a death with. For example, hall of fame NFL coach Tom Landry, singer Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, and Peanuts’ cartoonist Charles M. Schulz all share a death date. Schulz has a notability score of 3,048. Landry and Hawkins’ scores respectively sit at 42,792 and 9,530, meaning that the Charlie Brown creator likely overshadowed their deaths.

And he did! Schulz not only made the front page of The New York Times when he died, but he got a massive two-page spread inside. The Landry and Hawkins obituaries both shared part of page 32.

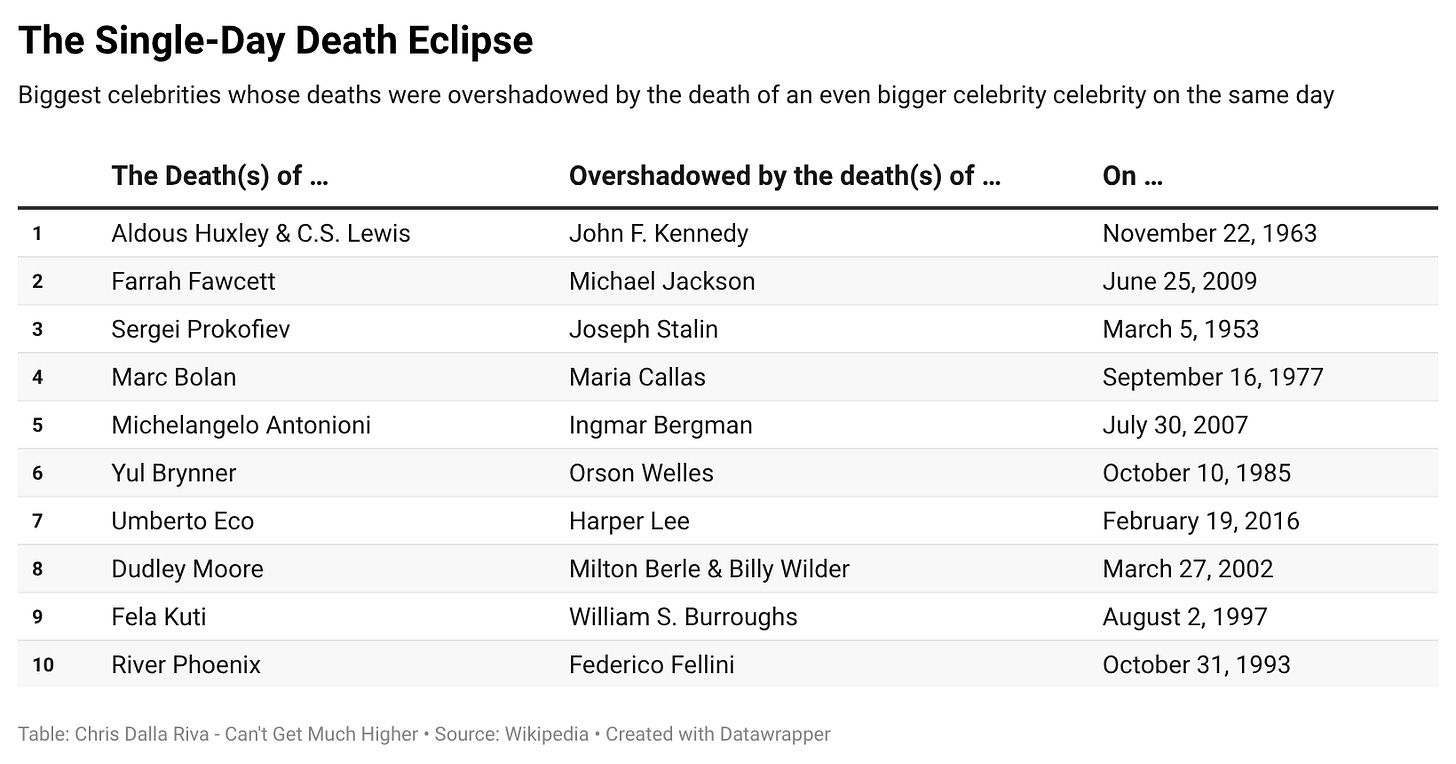

To be clear, I am not just looking for overshadowed deaths. If I died on the same day as a former US president, then my death would be overshadowed. But I’m not famous. My goal here is to find the most famous people whose deaths were overshadowed. With that in mind, there are no deaths more overshadowed than those of Aldous Huxley and C.S. Lewis.

Aldous Huxley and C.S. Lewis were both giants of the 20th century. Huxley, whose 1932 novel Brave New World is still taught regularly in high schools, was a prolific writer nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature nine times. C.S. Lewis was no literary slouch either. Along with creating the beloved children’s series The Chronicles of Narnia, he was one of the most important Christian theologians of the 1900s.

But when they both died on November 22, 1963, nobody seemed to care. That was the day that John F. Kennedy was assassinated. Kennedy’s death dominated the news cycle so thoroughly that the first 16 pages of The New York Times were dedicated to him the day after his death. It continued to be the top cover story over the next three days. Huxley and Lewis’s respective obituaries were eventually published, but their impact was clearly diminished.

Along with the previously mentioned Jackson-Fawcett and Stalin-Prokofiev overshadowings, some others include opera singer Maria Callas passing the same day as T. Rex frontman Marc Bolan, filmmaker Ingmar Bergman passing the same day as filmmaker Michelangelo Antonioni, and writer William S. Burroughs passing the same day as African music legend Fela Kuti.

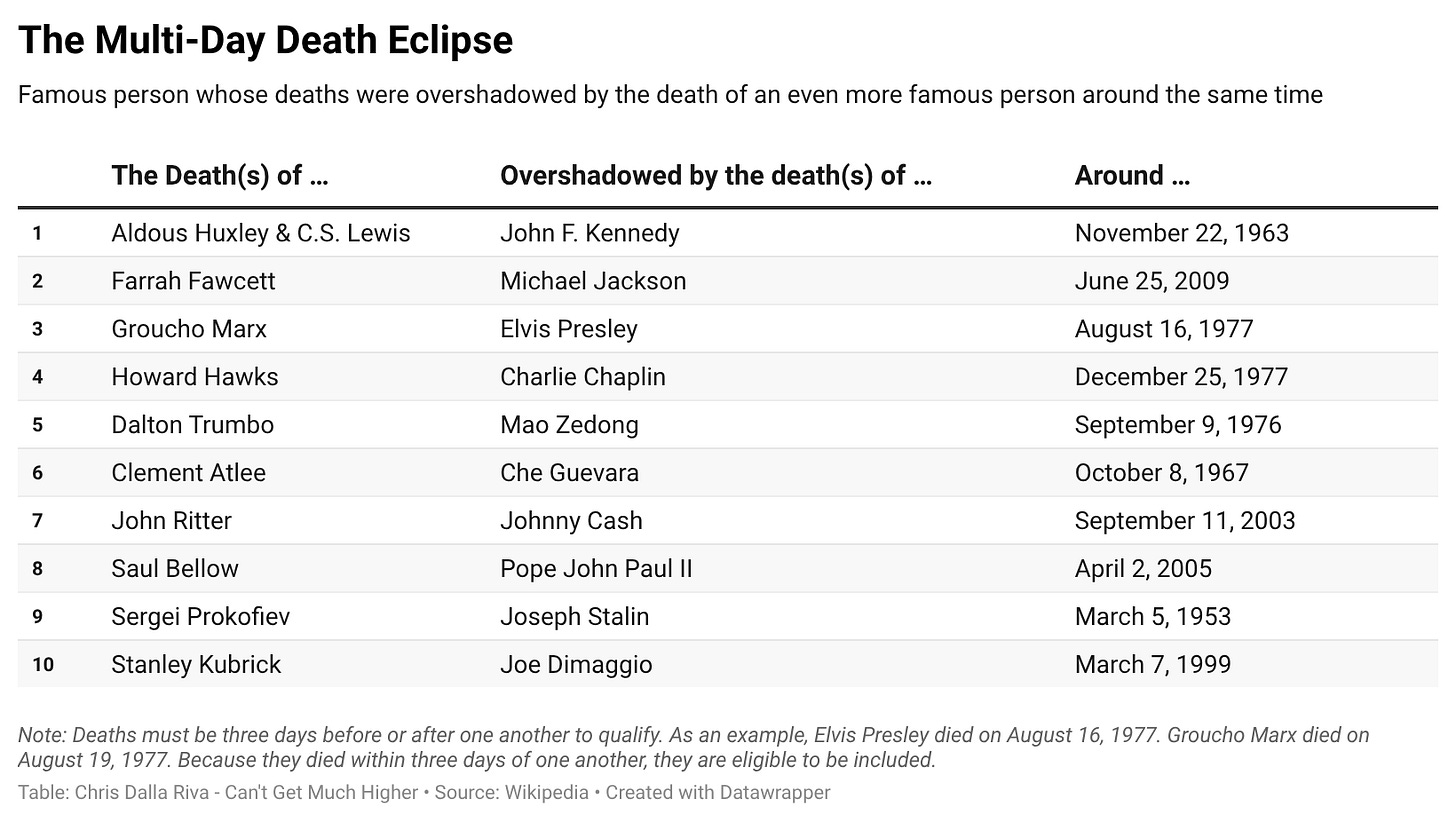

Maybe a single day is too narrow a scope for this exercise, though. I know that Groucho Marx died three days after Elvis Presley. I’m sure The King’s death muted some of the coverage that the legendary comedian would have gotten. Because of this, I decided to look for overshadowed deaths that were in a six-day window (i.e, three days before and three days after) rather than just on the same day.

Though Kennedy-Huxley-Lewis and Jackson-Fawcett still top the list when expanding the day range out, we get some other unexpected pairs. Howard Hawks gets overshadowed by Charlie Chaplin. John Ritter gets overshadowed by Johnny Cash. Saul Bellow gets overshadowed by Pope John Paul II.

Honestly, that last pair illustrates a general pattern I am seeing in this data. The most likely way a death is overshadowed is when a pop culture figure dies right around the same time as a major political or religious figure. It’s not even clear to me if the opposite has ever been the case.

The Ebbs and Flows of Notability

Of course, deaths don’t necessarily have to overshadow one another if they occur on the same day. The entertainer Sammy Davis Jr., for example, died on May 16, 1990, the same day as The Muppets creator Jim Henson. I’m sure the unexpectedness of Henson’s death took some of the spotlight away from the “I’ve Got to Be Me” singer, but they both got similar coverage in the paper.

The quintessential example of this phenomenon is John Adams and Thomas Jefferson dying on the same day—July 4, 1826, no less. By my metrics, Jefferson’s death overshadowed his one-time political rival and presidential predecessor. That said, I don’t think the third US president’s death buried coverage of the second’s in the same way JFK did for C.S. Lewis and Aldous Huxley. The notability of humanity is just diminished a bit more on certain days than others.

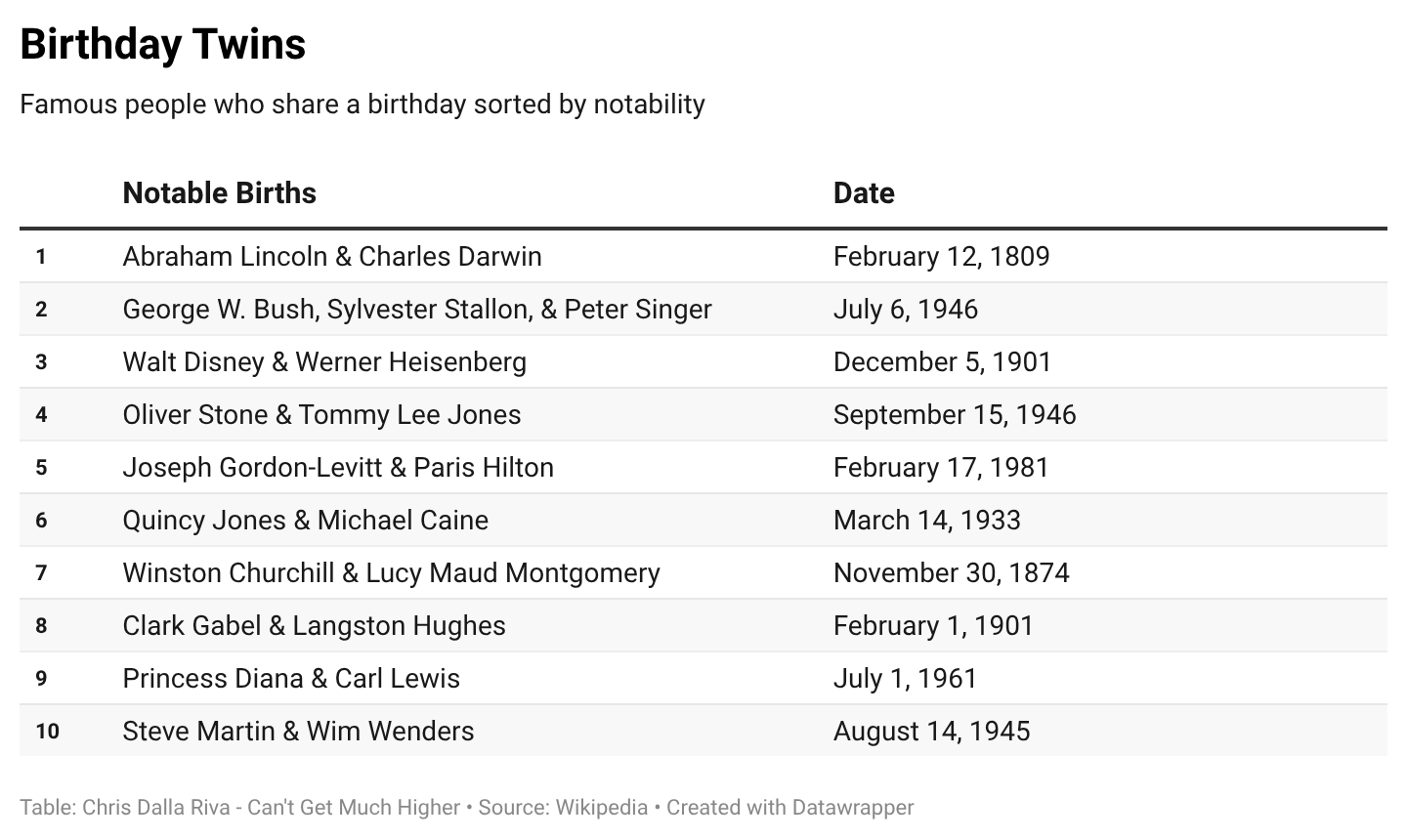

But it can also grow a bit more on certain days. In order to end this somewhat grim piece on a lighter note, I thought I should highlight times when notable people were born on the same day.

I don’t think anybody has a case for arguing that there has been a more accomplished birthday than February 12, 1809. Both Charles Darwin and Abraham Lincoln came into being on that date. The former discovered evolution by natural selection, maybe the most important theory in all of biology. The latter led the United States through a civil war and helped pave the way for the country to end slavery.

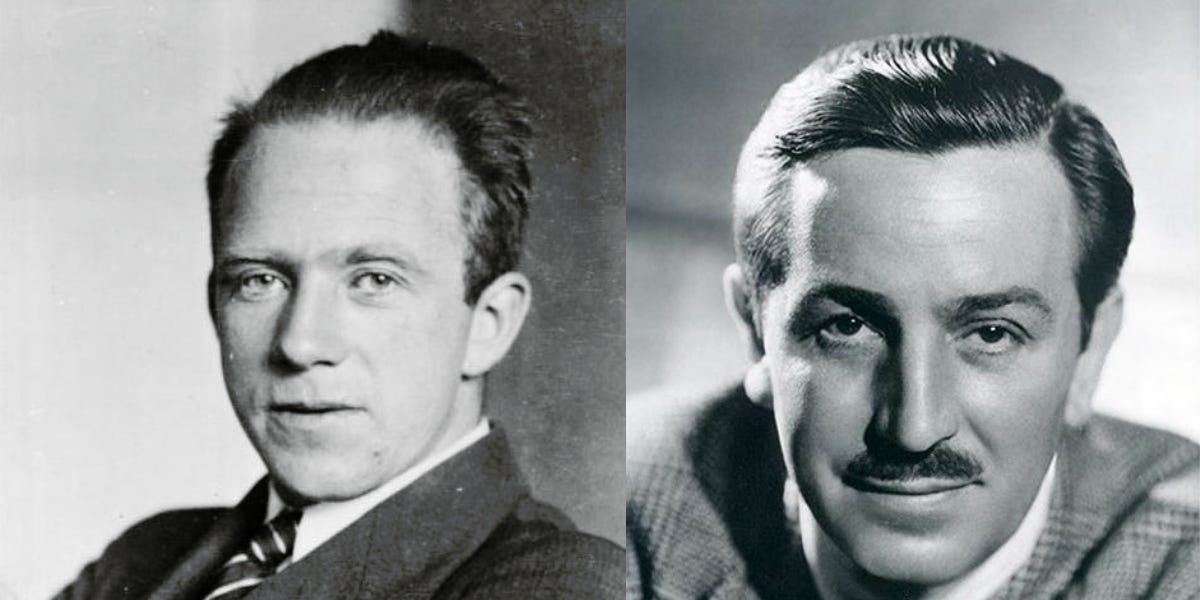

There are some other notable groupings, though. President George W. Bush, actor Sylvester Stallone, and philosopher Peter Singer all share a birthday. So do Walt Disney and Nobel Prize-winning physicist Werner Heisenberg.

Some pairings make it seem like the universe was winking, like actors Marilyn Monroe and Andy Griffith being born on the same day. Others create intrigue by how divergent their lives were, like politician Nikita Khrushchev and singer Bessie Smith both being born on August 15, 1894.

All that said, I think my favorite birthday is June 18, 1942. That is when musician Paul McCartney and film critic Roger Ebert both came into being. I like how McCartney and Ebert illustrate the importance of both artist and critic, albeit in different fields. When June 18 comes around this year, it’s a good reminder to make some art and then think deeply about it.

A New One

"Me Being Me" by Kenny Whitmire

2025 - Classic Country

After stumbling upon songwriter Kenny Whitmire on TikTok, I sent his latest song “Me Being Me” over to my friend Monica. “He hit on every single country cliche,” she noted after listening to the song. And she’s right. But I don’t think that’s a bad thing.

Cliches don’t work when an artist fails to realize what they are doing is cliche. Whitmire, by contrast, is clearly steeped in country tradition. He knows what he is doing. And it’s always a pleasure to listen to someone who has such command of a style of music.

An Old One

"Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out" by Bessie Smith

1929 - Blues

Originally written in the early 1920s, “Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out” became a standard when Bessie Smith—the birthday buddy of Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev—recorded it a month before the Great Depression began. Nearly a century later, her rendition—and the song itself—remains as powerful as ever.

If you enjoyed this piece, consider ordering my book Uncharted Territory: What Numbers Tell Us about the Biggest Hit Songs and Ourselves. The book chronicles how I listened to every number one hit in history and used what I learned during the journey to write a data-driven history of popular music from 1958 through today.

I wanted to mention the death of Princess Diana and Mother Theresa, which I thought both happened on (my birthday) August 31, 1997. But it turns out Mother Theresa died on September 5th, which didn't make the 3-day window. It just shows that when something personal, like my birthday, is involved, how memory can be skewed. Still, Diana's death definitely overshadowed Mother Theresa's death for weeks.

An adjacent idea. Former President Dwight “Ike” Eisenhower died March 28, 1969, immediately changing the plans for weekly news magazine cover stories. Janis Joplin is said to have lamented her being bumped from her expected appearance on the cover of Time magazine that week, with a “just my luck” kind of shrug.