An AI Band Went Viral. So What?

Or how I ended up in Rolling Stone magazine

If you’ve somehow missed it, I have a book coming out this fall. It’s a data-driven history of popular music covering the period from 1958 to 2025. I sent an early copy to Mark Richardson, the former editor-in-chief of Pitchfork and current rock/pop critic at the Wall Street Journal. Here’s what he had to say about it:

It's easy to forget that sitting around and talking music with friends is about as fun as it gets. Chris Dalla Riva captures the feeling of spirited in-person discourse about records in book form. He brings to the table a raft of knowledge bolstered by deep analysis of relevant data, so you'll learn something new on every page. But he also realizes that numbers in music are more useful for starting conversations rather than ending them, so you'll walk away remembering his ideas and opinions rather than stats.

If you want to see what Mr. Richardson is talking about, buy a copy today wherever books are sold. Now, let’s talk about a big AI hoax that’s been circulating throughout the internet.

An AI Band Went Viral. So What?

By Chris Dalla Riva

I thought I was hallucinating. I was reading an article on Rolling Stone, and suddenly my name appeared:

But how real was it? The songs, like “Dust on the Wind,” felt like generic reproductions of Seventies rock, and “photographs” of the group obviously had the amber-encased glow of AI-generated content. On Reddit, two posters called out what one poster called “a completely fake band”; musician and writer Chris Dalla Riva questioned their existence on TikTok; and the streaming service Deezer noted that “some tracks on this album may have been created using artificial intelligence.”

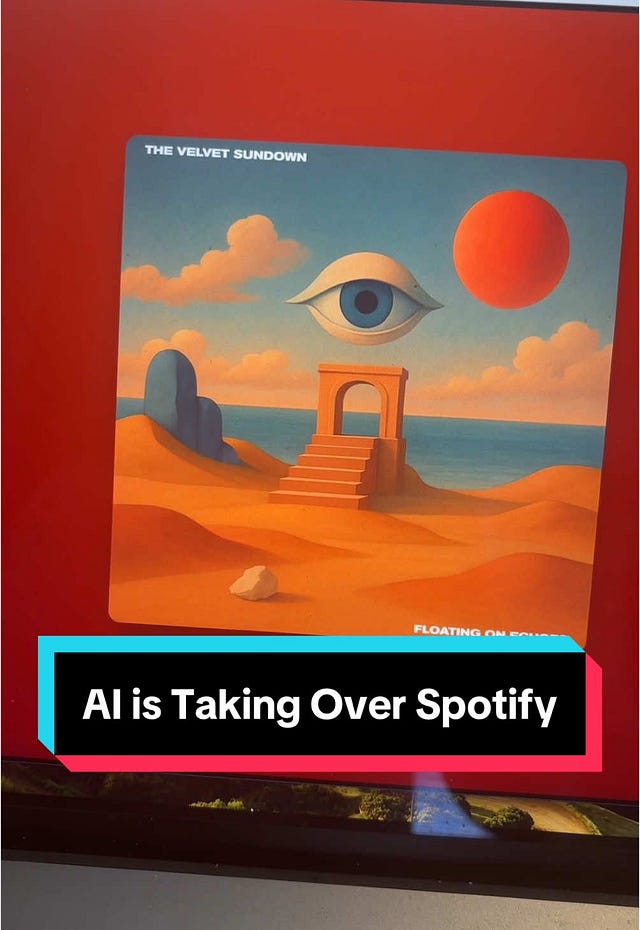

Let me give you the backstory of what’s going on here. Last week, a Reddit post suggested that a “band” with 300k monthly listeners on Spotify was completely generated with artificial intelligence. Literally everything. The music was AI-generated. The band bio was AI-generated. The photos and cover art were AI-generated.

Intrigued, I started poking around and agreed. Everything about this group, dubbed “The Velvet Sundown,” was almost certainly created with artificial intelligence. I got 20k views when I posted my findings to TikTok. A writer from the industry publication MusicAlly saw the post and mentioned me when they wrote about the hoax. Staffers at Rolling Stone presumably either saw the MusicAlly piece or my TikTok. Thus, my name was entered in the Rolling Stone corpus for first second time. (I thought this was the first time, but during the course of writing this piece, I found that last year the Italian version of Rolling Stone mentioned an article that I wrote.)

In the wake of their virality, The Velvet Sundown began to claim that the music was made by humans. “Absolutely crazy that so-called ‘journalists’ keep pushing the lazy, baseless theory that The Velvet Sundown is ‘AI-generated’ with zero evidence,” someone under the group’s name wrote on Twitter. “Not a single one of these ‘writers’ has reached out, visited a show, or listened beyond the Spotify algorithm.” Rolling Stone got them to admit that this was lie. Adam Frelon, a representative for the band, told the magazine that the whole thing was an “art hoax.”

While there are a million sources that you can consult — including my TikTok — if you want to learn why people began to suspect this music was AI-generated, I want to discuss what was used to create this music, how it ended up getting hundreds of thousands of streams, and why this is all very bad.

How to Create AI-Generated Music

Since the launch of ChatGPT in late-2022, we’ve seen scores of generative artificial intelligence tools crop up. These tools are called “generative” because they take an input from you and use that to create something, whether that be text, image, video, audio, or some combination. At present, the most popular generative audio tool is Suno.

We’ve covered Suno in this newsletter before. (It’s also covered in the last chapter of my book.) It’s pretty easy to use. You describe a song to it, and it spits back two recordings in a matter of moments. Below you can hear what I got when I asked for “A melodic hip-hop song with ukulele about buying a new car.”

Is it good? No. Is it crazy that this technology works at all? Yes. According to Rolling Stone, this is the technology that The Velvet Sundown used to create their music, albeit they upgraded to the paid tier, so they could have the same vocalist across tracks. For somewhere between $8 and $24 per month, they were able to output 26 songs that received hundreds of thousands of streams. Still, there are so many AI-generated tracks floating around online. How did these get so many streams?

How to Get Millions of Streams

A few years ago, I sent my coworker a Billboard article with the following headline: “1B French Streams Were Fake in 2021, Report Finds.” His response was short: “Only 1 billion?” He was (mostly) joking. But streaming fraud is a serious issue. With a quick Google search you can buy streams on almost any platform. You shouldn’t do this. It’s a great way to get banned from an internet platform because bots are usually used to generate the streams. It’s possible The Velvet Sundown just bought the plays. But I don’t think that’s the case.

One of the best ways to get streams on Spotify is to get their algorithms to recommend your music to other listeners. Sadly, you can’t just click a big button to trigger Spotify’s algorithms. You need to “show” Spotify that people are engaging with your track. If your friends are already tired of your annoying texts begging them to listen to your music, a great way to do this is to get added to a popular playlist. Getting on a Spotify-curated playlist is extremely hard. Luckily, there is an informal world of underground playlist curators who can help you out.

If you’re willing to trawl through Spotify’s search page, you can find popular playlists that list emails or Instagram handles in their descriptions. Follow the trail of links, and you can usually submit your songs to be featured on these playlists, albeit sometimes for a fee.

I am far from the first person to uncover this strategy. In fact, most large labels have curation branches that just manage popular playlists that are under their purview. Then if Spotify won’t playlist a new song, they can just add it to their own playlist to try to get the first few streams. The Velvet Sundown seems to have used a strategy like this to great effect.

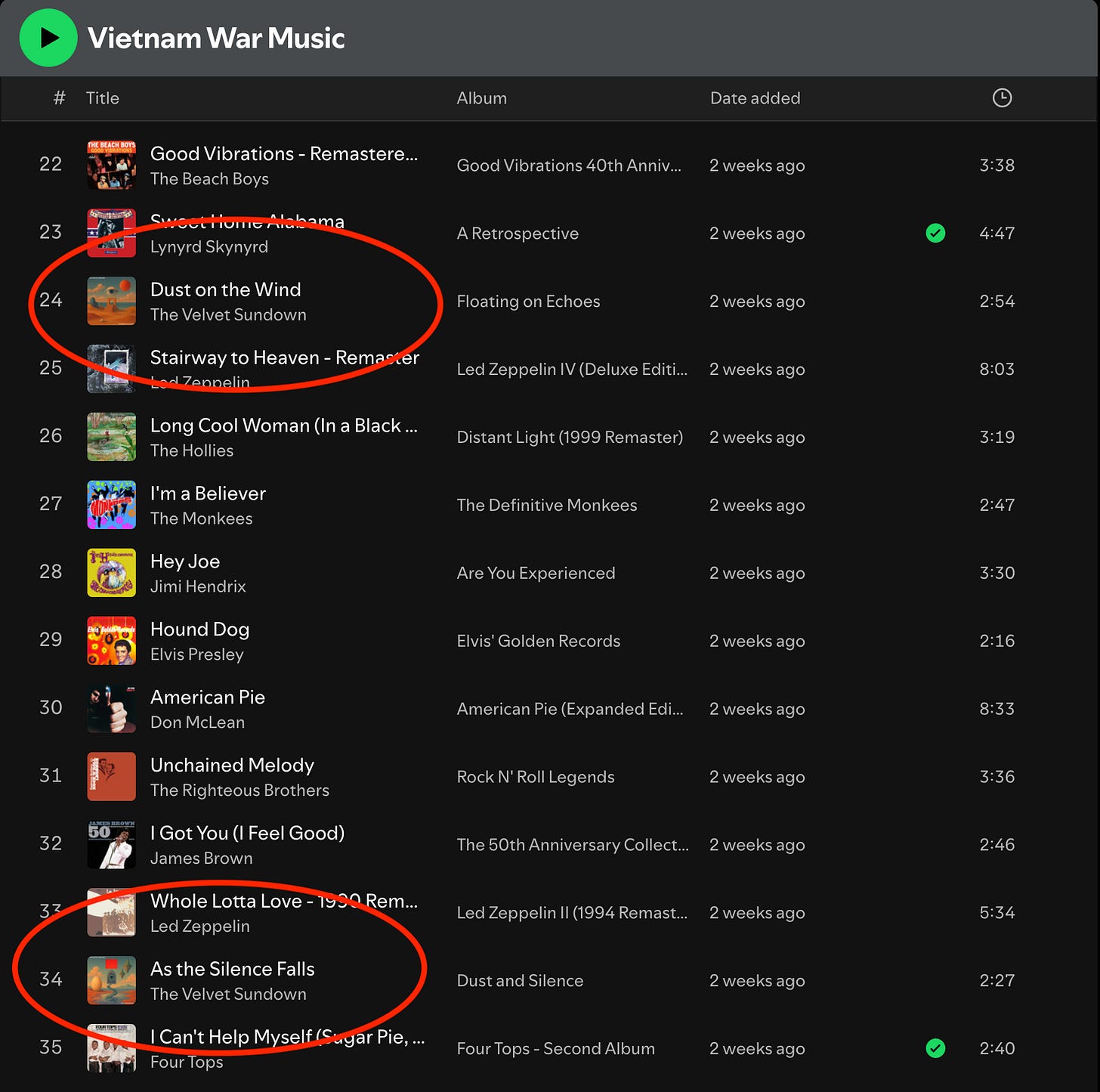

If you scroll down to the bottom of The Velvet Sundown’s page, you can see playlists they are featured on. The first playlist is “Vietnam War Music.” Most of songs on this playlist are what you’d expect: “Fortunate Sun” by Creedence Clearwater Revival, “Paint It, Black” by The Rolling Stones, and other songs from the late-1960s and early-1970s. But if you keep scrolling, you’ll notice assorted Velvet Sundown songs scattered throughout. That’s odd. All of their music seems to have been created decades after the last chopper left southeastern Asia.

The idea is that somebody will search “Vietnam War” on Spotify. They will see this popular playlist. They will shuffle it. They’ll mostly be happy with what they are hearing. Occasionally, a Velvet Sundown track will be snuck in. The unsuspecting listener will just assume it’s a song they are unfamiliar with. Eventually, the songs have generated enough engagement that Spotify’s algorithms start recommending the music to users. Voilà! You’re famous, or, in this case, infamous.

This situation only gets fishier because all of these popular playlists that The Velvet Sundown was added to seem to have come from a few accounts. In the Rolling Stone piece, the group’s representative claimed to not know anything about this, but I wouldn’t be so sure. In fact, I wouldn’t be shocked if the people behind The Velvet Sundown also ran the playlists.

Why is It Bad that a Fake Band Going Viral?

One of the most famous music industry scandals was when it was revealed that Milli Vanilli, the winner of Best New Artist at the 1990 Grammy Awards, didn’t actually perform any of their songs on their multi-platinum debut album, Girl You Know It’s True. (This scandal is also discussed in my book.) The songs were performed by two other people. Rob Pilatus and Fab Morvan were just chosen to front the group because they were better looking and more competent dancers.

People were not happy about this. In fact, their Grammy is the only time an award has ever been rescinded by The Recording Academy. Still, there are limits to how fraud like this can be perpetuated. You need to record the music. You need to find people to go along with your ploy. You’ve got to shoot an album cover. You’ve got to get a record contract. It’s a lot of work.

The problem with The Velvet Sundown, and other AI-generated music, is that it can be generated at scale. You could quite literally flood streaming platforms with hundreds, if not thousands, of AI-generated songs. Even if 99% of your music isn’t played at all, if 1% finds an audience, you could generate serious revenue.

This is a horrible incentive. Beyond federal regulation, the only way I don’t see the internet becoming overrun by AI-generated music is if streaming services and distributors decide to stop it. Right now, for less than $500 per year, you could create tens of thousands of songs with the help of AI and distribute them to every music platform on Earth. That’s not expensive.

You could argue that a good way to prevent this would be to raise the price of distribution. If you had to pay $1,000 a month to use Distrokid, you’d think twice about paying to deliver your AI-generated creations to Spotify and Tidal, among others. I don’t like that solution, though. I think it’s great that distribution has become democratized. A better first step would be to cap the number of songs an account can distribute per day, per month, and per year. People will certainly find workarounds, but we need to start thinking about these problems before every platform is overrun by musical bots.

A New One

"Greener" by CARAMEL

2025 - Alt. R&B

The Velvet Sundown got their music on Spotify through the popular independent distributor Distrokid. Here’s another song from a Distrokid artist, albeit one that reaffirms my belief that music will remain a very human endeavor despite the best efforts from our cyborg overlords.

An Old One

"Micky’s Monkey" by Mother’s Finest

1977 - Hard Rock

As depressed as some news about artificial intelligence and music can make me, I always try to remind myself that it is also just a new musical technology. Musical technology has led to apocalyptic dread for a century. People freaked out about recording and radio and electric microphones and drum machines and pitch correction too. As I noted in my book, we shouldn’t just assume a musical technology is bad because it is new.

I was oddly thinking about this while listening to Mother’s Finest’s hard rock cover of The Miracles’ “Micky’s Monkey.” You don’t get this killer cover without advances in studio recording technology. You also don’t get it without amplification. While I think I’ve laid out my case for why generative AI technology can be very bad, I want to close by saying that we should still try to remain open-minded even while we are skeptical. It’s possible that something useful might come out of this, something that makes me want to groove, like Mother’s Finest, rather than something that makes me want to scream, like The Velvet Sundown.

If you enjoyed this piece, consider ordering my book Uncharted Territory: What Numbers Tell Us about the Biggest Hit Songs and Ourselves. The book chronicles how I listened to every number one hit in history and used what I learned during the journey to write a data-driven history of popular music from 1958 through today.

Do we know anything about the band's "representative"? Could it be someone employed by Spotify or a Spotify-adjacent AI farm? Seeing that the "band" is on multiple DSPs it seems as if they're trying to cover their tracks, releasing through Distrokid etc

Interesting. How do consumers know if something is AI created?