Are the Grammys Sexist? An Update

Women have been dominating The Grammys. Does the trend hold up?

Last week, CNN invited me to their New York studios to talk about The Grammys. One thing we talked about was an essay that I wrote two years ago measuring the evolution of gender equality in the big categories at the award show.

Given that The Grammys were yesterday and that essay is two years old, I figured I’d run it again with updated data. And, as always, if you enjoy the stuff that I do here, consider purchasinga t copy of my book Uncharted Territory: What Numbers Tell Us about the Biggest Hit Songs and Ourselves. It’s a data-driven history of popular music that I wrote as I spent years listening to every number one hit in history.

Are the Grammys Sexist? An Update

By Chris Dalla Riva

In 1957, Sadie Vimmerstedt had an idea for a song. Vimmerstedt was not a songwriter. She was a 52-year-old widow who worked selling beauty supplies. But that would not deter her. She decided she was going to send the concept for the song to Johnny Mercer. Mercer was not an easy person to reach, though.

By 1957, Johnny Mercer was already one of the most legendary songwriters of all-time, winning multiple Oscars for Best Original Song and penning such classics as “That Old Black Magic”, “Jeepers, Creepers!”, and “One for My Baby (and One More for the Road)”. On top of that, he founded Capitol Records, one of the most successful labels at the time. None of this intimidated Vimmerstedt, though. She just penned a letter with her idea and addressed it to “Johnny Mercer, Songwriter, New York, NY.”

Rather than tossing it in the trash, someone at the post office decided to forward the letter to ASCAP, the performance rights organization that represented Mercer’s compositions. Someone in the ASCAP offices then gave the letter to Mercer. As reported in the March 12, 1963, edition of the Dayton Daily News, Mercer first responded to Vimmerstedt in 1959, two years after she’d initially written him. He apologized for his tardiness but told her that he would write the song.

Years went by before Vimmerstedt heard from Mercer again. When he reached out again, he told her that he wrote the song—now titled “I Wanna Be Around”—and was looking for someone to sing it. That someone ended up Tony Bennett. Bennett’s recording of “I Wanna Be Around” was a huge hit. Though she’d only supplied the germ of the idea, Mercer gave Vimmerstedt 50% of the writing credit. She never had to worry about money again.

“I Wanna Be Around” was later nominated for Song of the Year at the 1964 Grammy Awards. It lost to “Days of Wine and Roses,” another song co-written by the inimitable Mercer. Among many astounding facts about this story is that Sadie Vimmerstedt was only one of six women nominated for Song of the Year during the 1960s. This is a far cry from the 2020s when 47 of the 60 songs nominated for Song of the Year have had at least one woman credited as a songwriter. This made me wonder when things changed or if they changed at all. Were women still underrepresented at the Grammys?

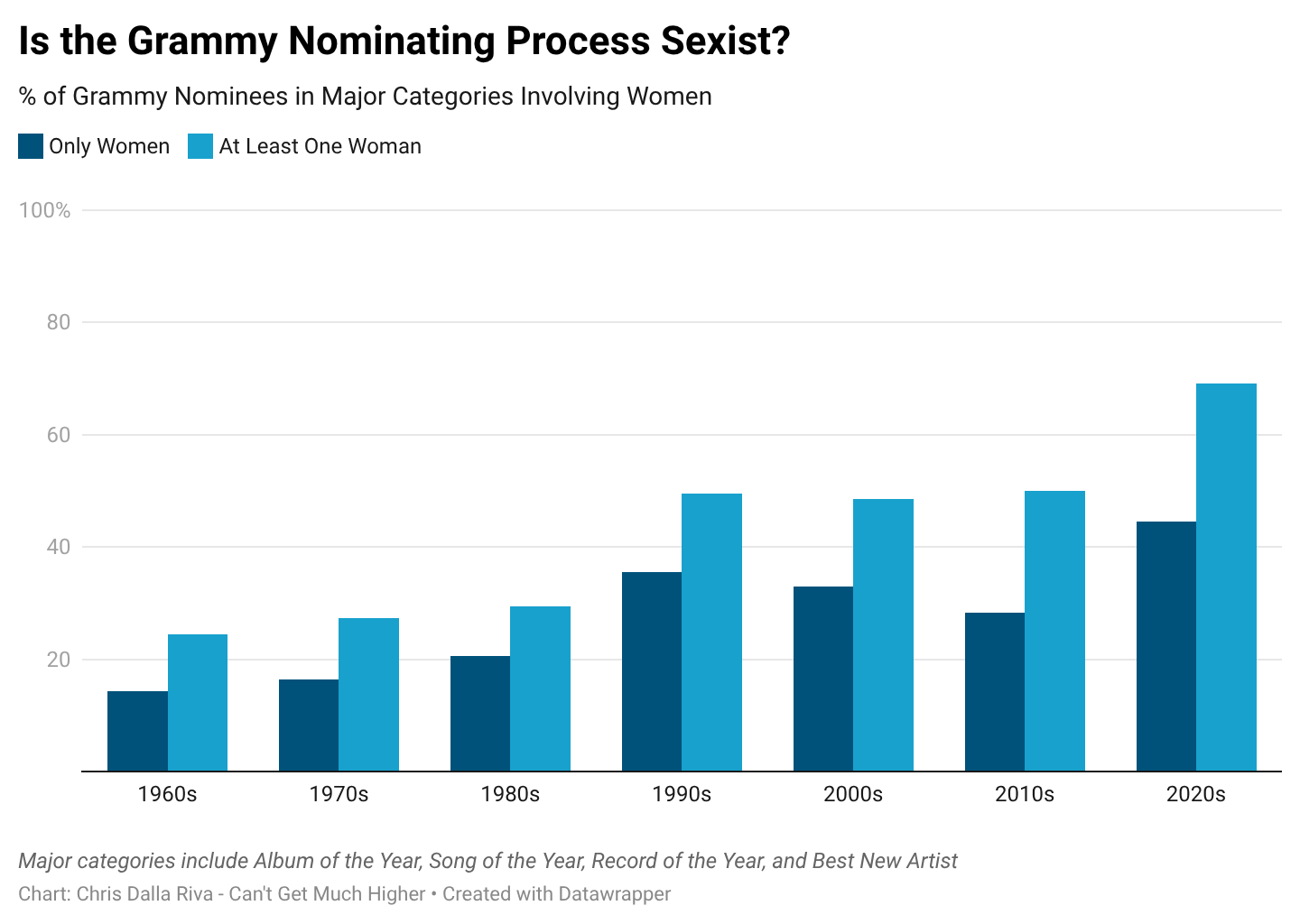

To answer these questions, I focused on the four most prestigious awards handed out by The Recording Academy: Album of the Year, Record of the Year, Song of the Year, and Best New Artist. All of these awards have been around effectively since the ceremony’s inception. Using these awards, we can try to see if there is evidence for sexism in both the nominating and winner-selection processes. Let’s start with the former.

I’ve elected to count women nominees in two ways. The more conservative approach—represented by the darker bar on the left—only counts a nomination if it involved no men. For example, when Alabama Shakes was nominated for Best New Artist in 2013, they were not counted by this methodology. Yes, the group is fronted by a woman, namely Brittany Howard, but the other members are men. By contrast, my more inclusive approach—represented by the lighter bar on the right—did count the Alabama Shakes. This approach counts a nomination if at least one woman was involved.

What we see is that from the 1960s through the 1980s, women were severely underrepresented in the Grammy nomination process for the four most prestigious awards. By the 1990s, things started to improve such that nominations were getting closer to 50% men and 50% women. To be clear, a single year with few women nominated is not strong evidence for underlying sexism in the nominating procedures. But over a longer period, we would expect nominations between men and women to be pretty much equal. As time has gone on, that is actually what we’ve seen.

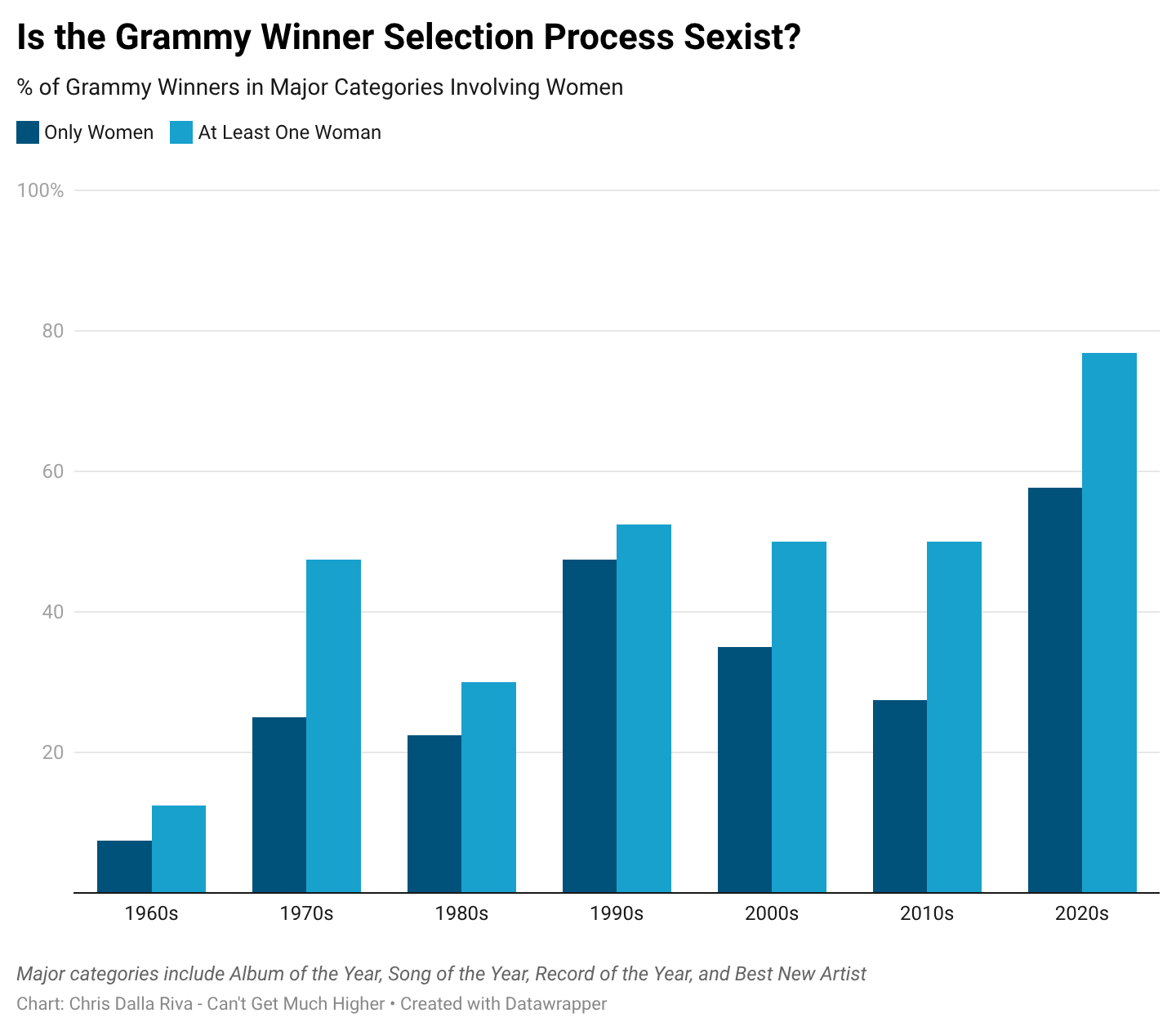

There is a similar pattern when looking at the winners of the big awards. Though women rarely won in the 1960s, it is extremely common for them to take home a trophy these days. That said, as I was looking through this data, I realized that just looking at the percentage of women who won wasn’t ideal. Let’s take the 1983 nominees for Record of the Year to understand why.

“Always on My Mind” by Willie Nelson

“Chariots of Fire” by Vangelis

“Ebony & Ivory” by Stevie Wonder & Paul McCartney

“Steppin’ Out” by Joe Jackson

“Rosanna” by Toto

When The Recorded Academy handed the gramophone trophy to Toto for their groovy recording of “Rosanna,” you couldn’t get mad about sexism in the winner selection process. There were no women nominated! As a voter, you had no choice but to vote for a man. In other words, the issue in this case isn’t tied to how winners are selected but how nominees are selected. We need to disentangle these two processes.

To do that, we are going to compare the percentage of women nominated across the major awards to the percentage of women who won. Let me explain why with another example. Across the decades, there have been 20 times where a single all-male act was nominated in a major award category. For example, here are the Best New Artist nominees in 1996:

Brandy

Alanis Morissette

Joan Osborne

Shania Twain

Hootie & the Blowfish

Despite Hootie and his backing band being the only men nominated, they took home the trophy that year. That doesn’t necessarily indicate sexism in the winner selection process. But if men consistently won awards where the odds were stacked again them, something fishy might be going on. That’s not the case, though.

Across those 20 awards where a woman was involved in four of five nominations, the all-male nominees took home the trophy 30% of the time. If we assumed that each nominee had an equal chance of winning, then we’d expect that percentage to be closer to 20%. Nevertheless, it’s not like men are winning 90% of the time when we would expect them to win 20% of the time.

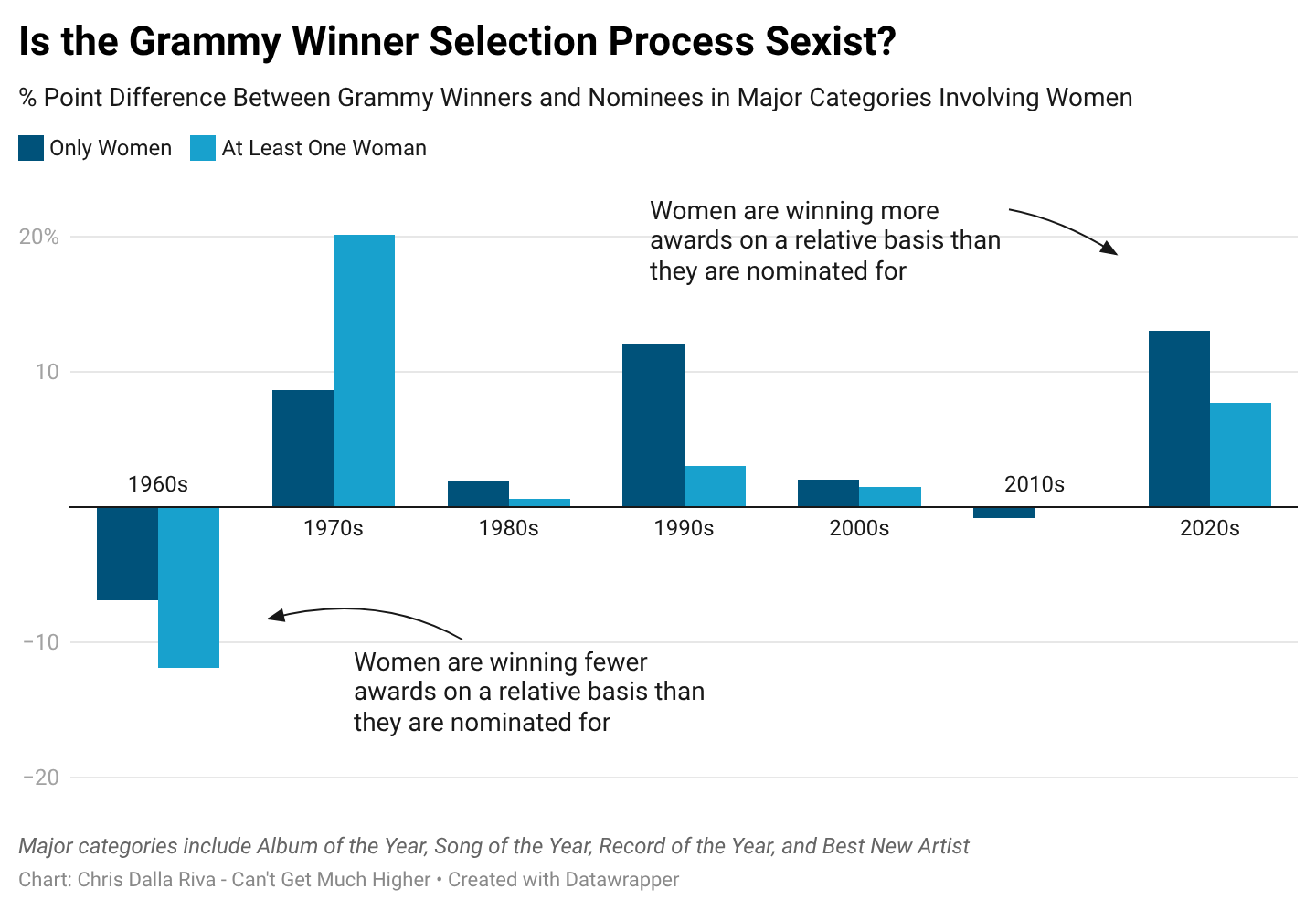

To do this at scale, I took the percentage of women who won within each decade and subtracted off the percentage of women nominated. In a perfect world, we would expect this difference to result in 0%. If the difference is negative, it means that men are over-indexing (e.g., 10% of nominees were men but they won 90% of awards). If the difference is positive, it means that women are over-indexing (e.g., 35% of nominees were women but they won 60% of awards). Here’s what we see when looking at the actual data:

In the 1960s, men consistently won more awards than we’d expect given the nominations. This could indicate sexism among those that selected the winners.

In the 1980s, 2000s, and 2010s, the results are almost perfect. For example, in the 2010s, 28.3% of nominees were only women and 50.0% of nominees had at least one woman. Within that same decade, 27.5% of winners were only women and 50.0% of winners had at least one woman.

In the 1970s, 1990s, and 2020s, women won more awards than we’d expect given the nominations they’d received. In fact, when we look across all the decades, women have beaten expectations.

Together this suggests more evidence for sexism in the Grammy nominating process than the winner selection process. If women are nominated, voters don’t seem to have a problem giving them a trophy. The historical issue has been that not enough women are nominated.

Of course, the data also tells us that things are much better today. That doesn’t mean that sexism is no longer a thing in the music industry. But we are thankfully far away from the world where rather than writing a song, a woman has to write a letter to a famous man to be taken seriously.

Thanks for reading. If you enjoy my work, please consider ordering a copy of my forthcoming book Uncharted Territory: What Numbers Tell Us about the Biggest Hit Songs and Ourselves. It’s a data-driven history of popular music that follows my journey listening to every number one hit from 1958 to 2025.

In the late '60s, we were very concerned at Motown that the Grammys were racist. Our answer was to have every qualified person in the company join the Chicago chapter. By the next year's Grammys, a number of Black artists had been nominated. Years later I learned that a rush of black members from all over the country had joined at that time. Because people are nominated by members, the balance of membership can make quite a difference. To its credit, the academy has been working very hard to diversify its membership and it's making a huge difference.

Very interesting, as well as informative, as always. 👍