Don't Believe the Headlines. Music Festivals Aren't All the Same.

Many publications claim that music festival lineups are becoming more similar. I decided to investigate.

If you’ve been following my series about every concert that I’ve seen, you’ll know that I love music festivals. So far, I’ve been to four: Bonnaroo, Austin City Limits, Boston Calling, and Bamboozle. I’ve had a great time at all of them. But over the last decade, headline after headline has claimed that music festivals are all the same.

New York Times (2015): “Music Festivals Scramble for the Same Headline Talent”

Quartz (2016): “It’s true. Every music festival is starting to look the same”

USA Today (2019): “America's biggest music festivals are more skippable than ever”

GQ (2019): “How to Pick a Music Festival When They All Sound the Same”

Vice (2023): “Why Do All the Festival Lineups Look and Feel the Same?”

As you can see, most of these articles are five to ten years old. Additionally, they are generally small in scope, looking at just a year or two to come to their conclusions. Because of this, I decided to weigh in on this debate. Before I do, I’m excited to announce that this newsletter is now available as a podcast! Click to listen on Apple, Spotify, or Substack.

Bonnaroo-chella-palooza

If you wanted to go to a big music festival in 2023 but stipulated that Kendrick Lamar be one of the headliners, you were in luck. The Compton rapper was performing at Austin City Limits, Bonnaroo, Governors Ball, Lollapalooza, Open'er, Osheaga, Outside Lands, Primavera Sound Barcelona, and Roskilde. In other words, you could make a musical pilgrimage to Denmark, California, Spain, Texas, and a few other places and still get to shout along to Lamar’s hit song “HUMBLE.”

But was Kendrick Lamar being booked at tons of festivals in 2023 an industry-wide trend? Or did he just happen to finagle a ton of bookings that year? To answer this question, I collected every artist that was booked between 2013 and 2023 at 12 major festivals: Austin City Limits, Bonnaroo, Coachella, Glastonbury, Governors Ball, Hangout, Lollapalooza, Open'er, Osheaga, Outside Lands, Primavera Sound Barcelona, and Roskilde. I then sliced and diced those bookings in a bunch of different ways to try to understand if festivals were becoming more homogenous. Before we get to the nuts and bolts of this homogeneity question, here are some miscellaneous facts that caught my eye.

Across the decade, there were 15,226 total bands and 6,876 unique bands booked across these festivals, meaning that 45% of acts were booked at least two times

Only seven artists played at all 12 festivals over the decade: Kendrick Lamar, Tame Impala, Haim, Father John Misty, Mac DeMarco, FOALS, and Lizzo.

Chromeo and Vince Staples set the record by playing 10 of the 12 festivals in a single year. Chromeo did it in 2014. Vince Staples did it in 2016.

Now, let’s turn back to the important question at hand: Are major music festivals booking the same acts more frequently? The simplest way to answer this question is to look at a uniqueness rate, meaning what percentage of artists were booked at exactly one of the 12 festivals in any given year. The answer: most.

Within any year in the decade, between 68% and 85% of acts were only booked at one festival. That 85% occurred in 2020 when many festivals either never announced a lineup or canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic. If we ignore 2020 and 2021, when much of the same thing occurred, the upper bound of that range goes from 85% to 77%. In other words, most acts on a festival lineup are only going to be on that one lineup. Furthermore, the relative number of acts only booked on a single lineup has increased. In 2013, the uniqueness rate was 70%. In 2023, it was 77%.

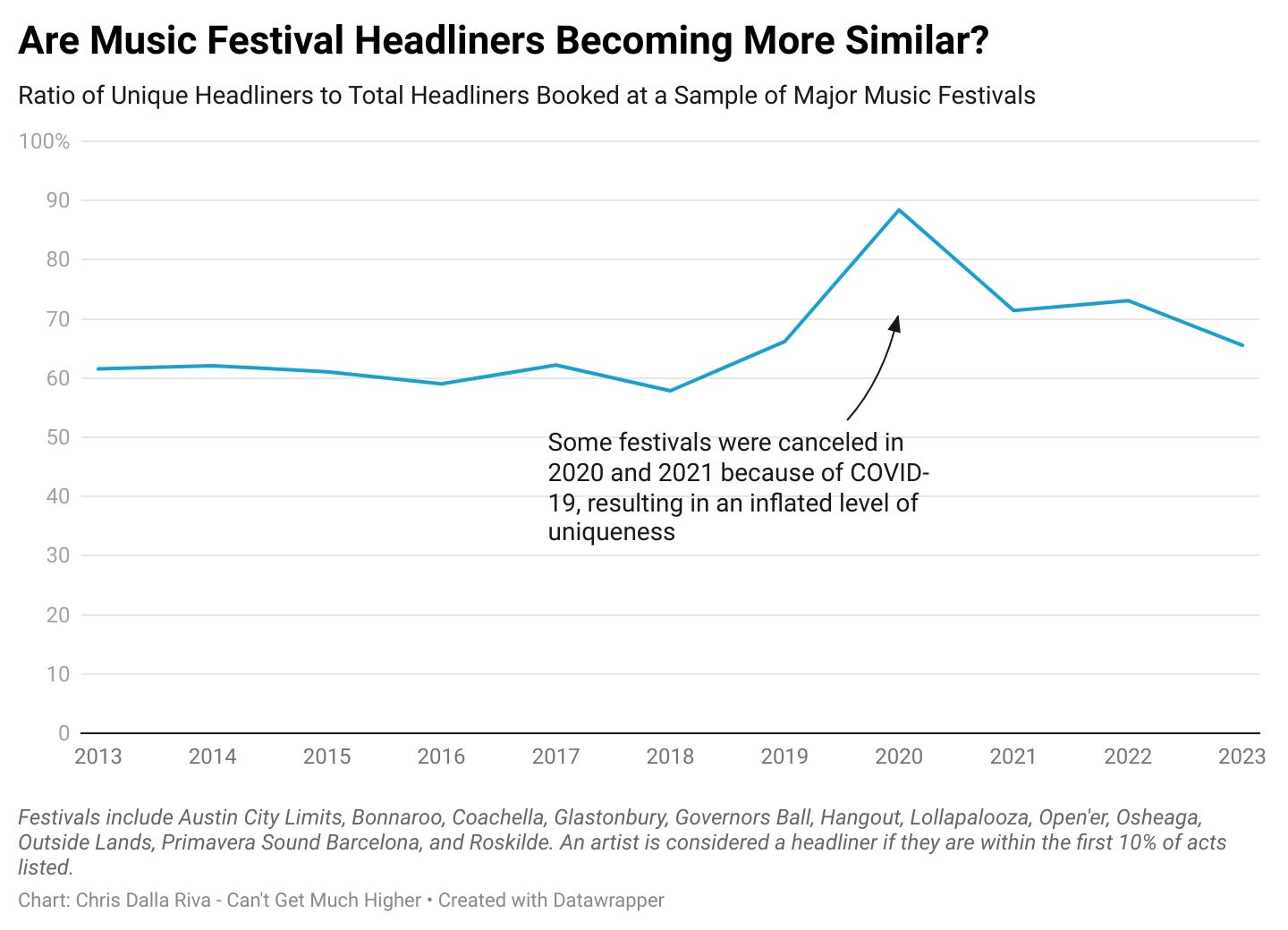

Maybe looking across entire festival lineups isn’t fair, though. Coachella, for example, booked over 150 musical artists in 2023. Glastonbury booked over 240. To flesh out a lineup that large, festivals need to book a bunch of small, unknown acts that aren’t going to get booked elsewhere. Maybe if we focus exclusively on headliners, or the first 10% of artists to appear on a lineup, we will see a different pattern. We don’t.

Within any given year in the decade, between 58% and 88% of headliners were only booked at one festival. There is generally less uniqueness than when looking across the entire lineup, but this is still quite unique. Even in the worst year, there was almost a 60% chance that whoever was headlining one of the festivals was not appearing at any of the others. Furthermore, the headliner uniqueness rate increased from 62% to 66% across the decade.

At this point, I was scratching my head a bit. As I mentioned earlier, you don’t have to look very far to find a bunch of articles claiming that every major music festival is now the same. Here, for example, is a quote from the 2019 USA Today article lamenting music festival homogeneity:

Last week saw the rollouts of the Lollapalooza and Woodstock 50 lineups, and despite their drastically different locations, the tops of their lineups didn't look much different from Coachella, Governors Ball, Boston Calling, Bonnaroo and the rest of America's biggest festivals.

The best advice for fans clamoring to get tickets? Save your money, considering music festivals have turned into a homogenized gimmick for big businesses that barely allow concertgoers the serendipity of discovering new acts.

That is a bold claim that I don’t see much proof for. Still, I wanted to give this perspective a fair shake. It is the online consensus. And given the amount of consolidation in the live event space, it would make sense if lineups were becoming more similar.

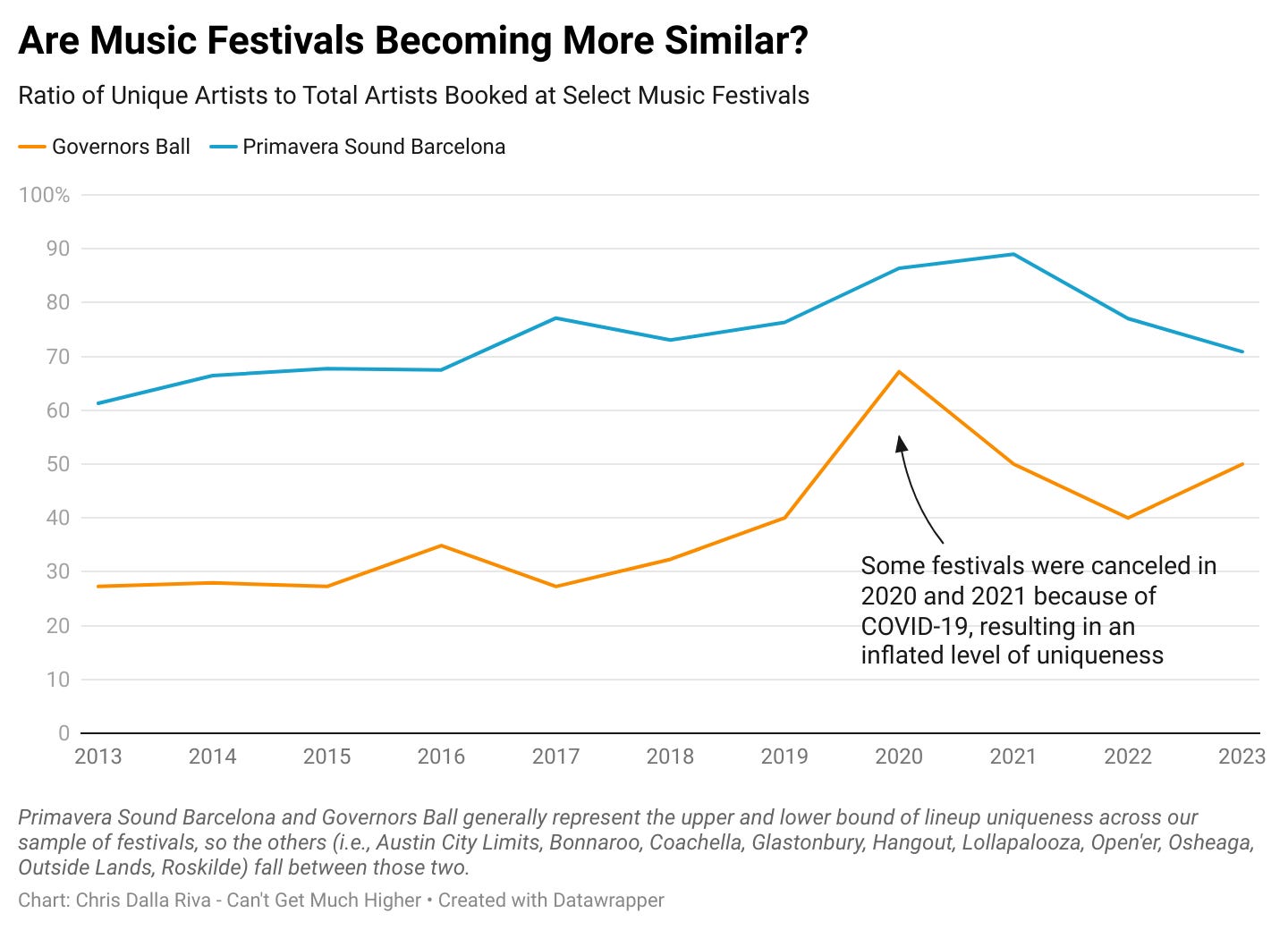

One way that I thought my analysis could be biased is if larger festivals booking tons of unique acts is drowning out the homogenization of smaller festivals. To try to understand if this was the case, I took Primavera Sound Barcelona — the largest, most unique festival — and compared it to Governors Ball — the smallest, least unique festival. I did this because the uniqueness rate of basically every other festival will fall between these two.

In 2013, only 27% of artists booked at Governors Ball were not booked at another festival in our sample. What that means in practice is that if you were busy during the June weekend that Governors Ball occurred, you could have waited two months and caught 33% of those Gov Ball acts at Lollapalooza.

By contrast, 61% of acts booked at Primavera Sound Barcelona in 2013 were booked at no other festivals in our sample. So, if you wanted to see Jesus & the Mary Chain at one of these 2013 festivals, you’d have to get a ticket to Primavera Sound Barcelona.

In other words, uniqueness is highly dependent on the festival. That said, every festival except for Open'er and Roskilde saw their uniqueness rate increase across the decade. So, despite the range of uniqueness, it does seem like festivals are getting more unique rather than less unique.

What about headliners, though? Do they tell a different story? Somewhat. Four of 12 festivals saw the uniqueness rate for their headliners decrease between 2013 and 2023. Furthermore, headliner uniqueness is notably lower than all lineup uniqueness. In fact, some festivals — like Osheaga in 2016 — had no unique headliners within a given year.

Still, this might not be the best way to look at this. The Lumineers were one of those Osheaga 2016 headliners. Among the festivals we tracked, the only other that they headlined in 2016 was Glastonbury. Is it fair to penalize Osheaga because one of their biggest artists booked one other big festival? Probably not. I’ll spare you the details about calculating a weighted uniqueness rate per festival and just tell you what I think all of this means.

In the last decade, music festivals have generally gotten more unique at the full lineup and headliner level.

Uniqueness is highly dependent on the festival, though. Certain festivals will book acts that you can see at scores of other locations while others will book more exclusively.

Most complaints about festival homogeneity are driven by people noticing a few headliners on multiple lineups. This bias doesn’t really reflect festival evolution at large.

Keeping these ideas in mind, I think there is one criticism that largely rings true. As time has gone on, major music festivals have less of an identity. Let’s take Bonnaroo as an example.

When Bonnaroo emerged in 2002, it focused on rock music with a heavy bias toward jam bands, including Widespread Panic, String Cheese Incident, Umphrey’s McGee, and various projects made up of members of The Grateful Dead and Phish, respectively. Though I think Bonnaroo is the major festival you are still most likely to see jam bands at — in fact, they are the only festival we tracked to book Phish in the last decade — they now offer a much wider variety of music, including hip-hop, EDM, and pop.

This is a pattern we’ve seen at most major festivals, and it’s likely been accelerated by the fact that many of these festivals are now owned by major corporations. Live Nation, for example, now owns Bonnaroo, Governors Ball, and slew of other festivals. As Live Nation chases larger profits, they likely need their bookings to attract as many people as possible.

Nevertheless, if you haven’t been to a music festival, I recommend you go to one. And I don’t just mean one of these giant festivals. There are scores of great genre-focused festivals all over the world. Festivals are a fantastic way to be exposed to a ton of talented musicians in a short amount of time. I wouldn’t know many of the bands I like today had I not traveled hundreds of miles to roam festival grounds, following my ear wherever it took me.

A New One

"Pick Up Your Phone (Acoustic)" by Tanner Usrey

2024 - Alt-Country

One of my favorite traditions each year is to trawl through festival lineups looking for new artists to listen to. There’s usually a ton of talent scattered throughout lineups, especially in the small text at the bottom. While I was looking through lineups this year, I came across an interesting artist on the last line of Bonnaroo’s day three lineup: Tanner Usrey.

Usrey, a country singer with some soul buried in his voice, had been making music for years when he got a surprise email from Paramount. They wanted to use his song “The Light” in the hit show Yellowstone. On the back of that sync and a growing fanbase, Usrey signed to Atlantic Records and released Crossing Lines, his major label debut. Recently, he put out a deluxe version of that record which included some acoustic renditions of previously released songs. One of those was acoustic version of “Pick Up the Phone”, a burning ballad with hints of Tyler Childers that hits like a punch to the gut.

An Old One

"I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin'-to-Die-Rag (Live)" by Country Joe & The Fish

1969 - Psychedelic Folk Rock

I’m convinced that everybody has a song that they heard when they were young that they knew their parents wouldn’t have wanted them to listen to. For me, it was Eminem’s “My Name Is”. I was at my friend Jake’s house in elementary school when his older brother put the song on while we played Nintendo 64. I was not only appalled by Marshall Mathers’ grotesque rhymes, but I was 100% certain I didn’t want my mother to know that I’d heard them.

I’ve asked people older and younger than me about this universal experience. When I posed this question to my Uncle Frank, my mom’s oldest brother, he noted a few songs, but the first that came to mind was Country Joe’s performance of “I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin'-to-Die-Rag” at Woodstock. A Vietnam protest anthem, Country Joe’s trippy rag is just as fiery as when it came out in the 1960s.

I’ve never played a music festival, but I do make music. Check out my latest single “Move On Up” wherever you stream music.

Festivals are always a fun subject, among musicians.

Unless you're among that top 10% "Big Print" group of artists, they mean a lot of hauling out to remote locations, getting dumped onstage in broad daylight (a terrible disadvantage with some kinds of music) with production values approaching zero; trying frantically to make an impression upon people at a time when they're basically wandering around trying to find their friends. Or food.

You have no room for being "present" in the moment, a hard time-limit, and the next band after you looking over your shoulder waiting for you to be done. An hour after your last note rings out, it's like you were never there.

The festival itself cares about its brand, and nothing about yours; so bands with really good management only do one in a year, specifically targeted for their genre-market, or none at all. The money and impact is honestly 10-100x better playing at whatever nearby club there might be the night before the fest begins.

If you're on a label, they'll tout it to you as "exposure" or "discovery" as a way to elide the tiny compensation for all that work, and it's not unusual for them to dump out the bottom of their rosters into the small print of these festivals as a brutal Darwinian test for those groups.

That's the other reason why you'll see so many different bands on different lineups. Not every one of them survives as a signee after.

Dang! This is a real good read. Lots of info packed into this one. I’m usually an observant person and I never really looked into festival lineups across the board this way. This is a little eye opening for me. That being said, glad that festival uniqueness is becoming a thing. Hopefully the trend continues as it’s clearly needed.