Investigating Fraud on the Billboard Charts

Today, I'm excited to share another excerpt from my debut book, Uncharted Territory

If you read this newsletter regularly, you’ll know that I have a book coming out this fall. It’s a data-driven history of popular music called Uncharted Territory: What Numbers Tell Us about the Biggest Hit Songs and Ourselves. If you’re a fan of the newsletter, you’re sure to like the book.

Each month until publication, I am sharing an excerpt from the book. Last month, I shared a piece of Chapter 10, which focused on the evolution of sampling in the period from November 9, 1996 to February 14, 2004. This month, I want to go further back in time and share an excerpt from Chapter 5 where I investigate if the Billboard charts were rigged in the 1970s. The only thing you need to know is that if a song is followed by a date (e.g., “Nothing From Nothing” by Billy Preston (October 19, 1974)), then that song was a number one hit and that was the date it topped the charts.

And Then She Turned on the Radio

An Excerpt from Chris Dalla Riva’s Uncharted Territory

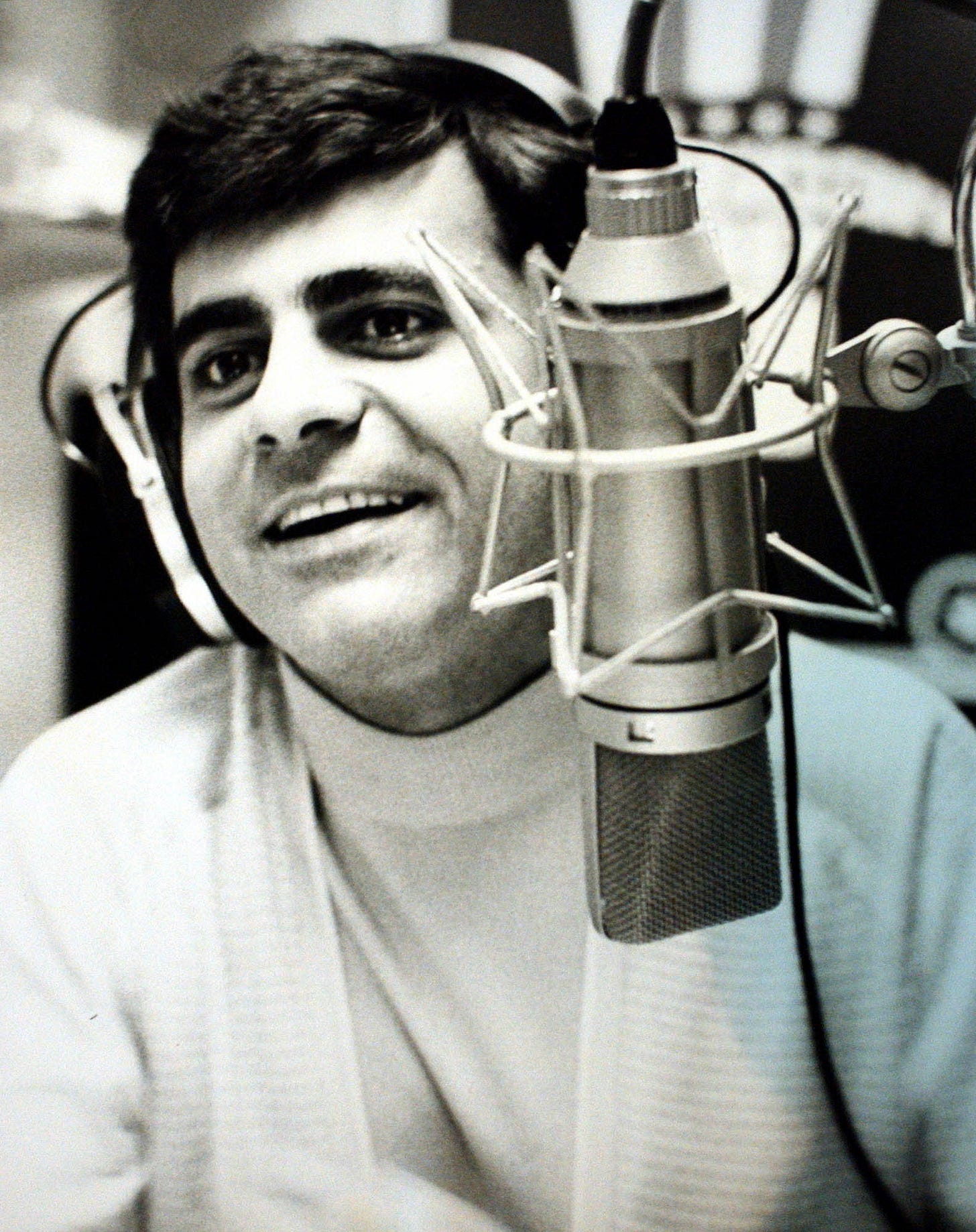

When Casey Kasem died in 2014, almost every major news outlet published a laudatory obituary. The Los Angeles Times named him “among the nation’s best known—and ubiquitous—radio personalities.” Time wrote that he was “one of the most important disc-jockeys in the history of radio.” The New York Times said he was known for “creating and hosting one of radio’s most popular syndicated pop music shows.”

None of these assertions were exaggerations. Kasem’s program—American Top 40, often shortened to AT40—began broadcasting on fewer than ten stations on July 4, 1970, but then swelled in popularity over the next few years. At its height, it was broadcast by hundreds of stations to millions of listeners. Coupled with the fact that Kasem also provided the voice for Shaggy on the TV series Scooby-Doo, he had one of the most recognizable voices in America in the second half of the twentieth century.

His show’s premise was simple: Each week he would count down Billboard’s top 40 songs. This was not the first show to exclusively play the most popular records in the land. Top 40 radio allegedly goes back to a man named Todd Storz. Around 1950, Storz was at a diner and noticed that the patrons kept playing the same songs on the jukebox. “Why not just program a radio station to play a short selection of songs on loop?” he pondered. Noting that a jukebox held about 40 songs, he dubbed his new programming format “Top 40.” It caught on fast. Kasem was part of the Storz lineage.

Because AT40 used Billboard to seed its playlist, between 1974 and 1983, Kasem’s show was controlled by a man named Bill Wardlow. During that time, Wardlow oversaw the compilation of Billboard’s charts. I have no proof that these two men ever met, but during this era, they symbiotically fed off one another, Kasem’s popular show building Wardlow’s industry clout and Wardlow’s chart doing the same for Kasem.

Nevertheless, there wasn’t much fanfare when Wardlow died in 2001. Here’s what Billboard, his ex-employer, had to say upon his passing: “Willis ‘Bill’ Wardlow, former associate publisher and director of charts for Billboard, died Dec. 29, 2001, in Los Angeles at age 80. Known as the ‘father of disco,’ Wardlow worked in the music industry for 55 years, including stints at Columbia and Capitol Records.”

There’s a bit to unpack here. Primarily, this obituary is short. I’m not expecting Billboard to dedicate the cover to him, but 44 words feels curt, especially for someone who ran their charts during the magazine’s expansion and pushed them to cover the burgeoning dance music scene. This brings us to the second oddity: Wardlow is referred to as the “father of disco.”

Disco was created in nightclubs of New York City that largely catered to a Black and gay audience. In the wake of the 1969 Stonewall riots, the gay population was looking for safe spaces where they were free to be themselves and listen to the music they wanted. The spaces that emerged—like The Loft, Sanctuary, and Gallery—were socially and musically radical.

In the decades leading up to the 1970s, if you went out to hear live music, there were two things that were true. You were seeing a band, and that band was performing for you. Though it’s commonplace now, at the time the idea of going somewhere to listen to someone play records was strange. If you wanted to listen to records, you could do that at home. DJs turned record-selecting into performance art.

But that wasn’t the only radical thing they were doing. Their choice of records allowed them to create an open space where club-goers could focus on one another rather than a performer. This turned the historical audience-performer relationship on its head. It almost goes without saying that a middle-aged White man like Bill Wardlow had little to do with this revolution.

Still, Wardlow and Billboard brought more legitimacy to the disco scene by documenting it. And disco was tremendously popular during this era. The shortness of his obituary just made it seem like his ex-employer had a problem with him. According to Frederic Dannen’s book Hit Men: Power Brokers and Fast Money Inside the Music Business, they did: Bill Wardlow was fired from Billboard in April 1983 over his mishandling of the charts.

The Case for Fixing the Charts

From labels run by the mob to shady artist contracts, there has always been a degree of corruption lurking in the music business. Of course, corruption lurks in every industry, but music industry corruption is partially driven by the fact that it’s a hits-driven business.

Say you’re Hugh Hefner, and you want to start a record label that shares the name with your titillating magazine, Playboy. Most of your releases are flops, but then Hamilton, Joe Frank and Reynolds top the charts with their meandering ballad “Fallin’ in Love” (August 23, 1975). That one big single will likely compensate for most of your losses. Because of that, there are strong incentives to do whatever you can to get people to listen to your record, even if that means paying radio DJs to play your songs.

This practice of artists and labels paying DJs to play specific songs, commonly referred to as “payola,” came to a head in the late 1950s and early 1960s when Congress hauled hundreds of radio DJs to Washington, D.C., for a hearing about the practice. After multiple radio personalities admitted to taking thousands of dollars in exchange for song placements, Congress amended the Federal Communications Act to force broadcasters to disclose if they were paid to play something. Payola, it seemed, was dead.

Not really. The law was never really enforced. Plus, independent promoters cropped up in the wake of the scandal who would shower DJs with drugs, money, sex, and whatever else they wanted to get songs on the air. Nobody would crack down on this evolved payola until the 1980s. Nevertheless, when something corrupt is going on, fraudsters usually leave a data trail.

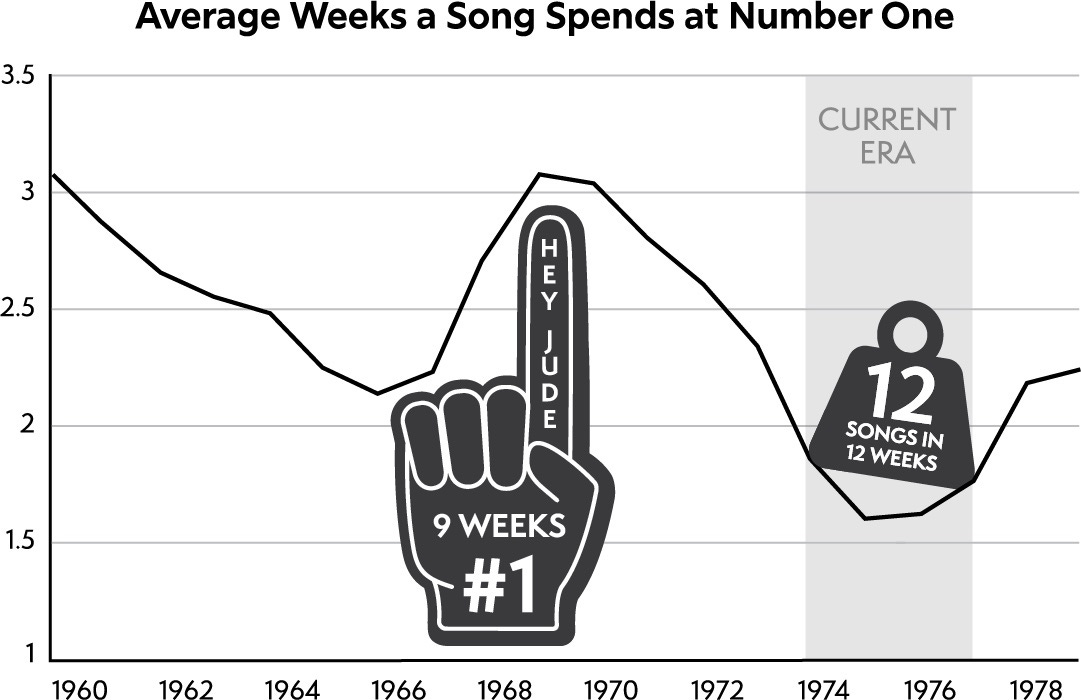

In Figure 5.1, you can see that between 1958 and 1970, number ones typically spent two to three weeks atop the charts. There was variation, but one-week chart-toppers were not common, only occurring about 27 percent of the time. Then things changed. By the middle of the 1970s, the average time atop the charts fell close to 1.5 weeks with nearly 50 percent of number ones between 1970 and 1977 only leading the chart for a single week.

This does not technically mean something illegal was going on. But it’s suspect. If you wanted to maximize your revenue for selling placements at number one, you’d probably want a ton of turnover. The oddities don’t stop there, though.

Besides Billboard, other magazines ranked popular songs at the time. Take Cashbox as an example. From 1958 to 1972, Billboard and Cashbox listed the same number one in 64 percent of weeks. Between 1973 and 1978, the match rate fell to 48 percent before returning to 71 percent in the period from 1979 to 1984.

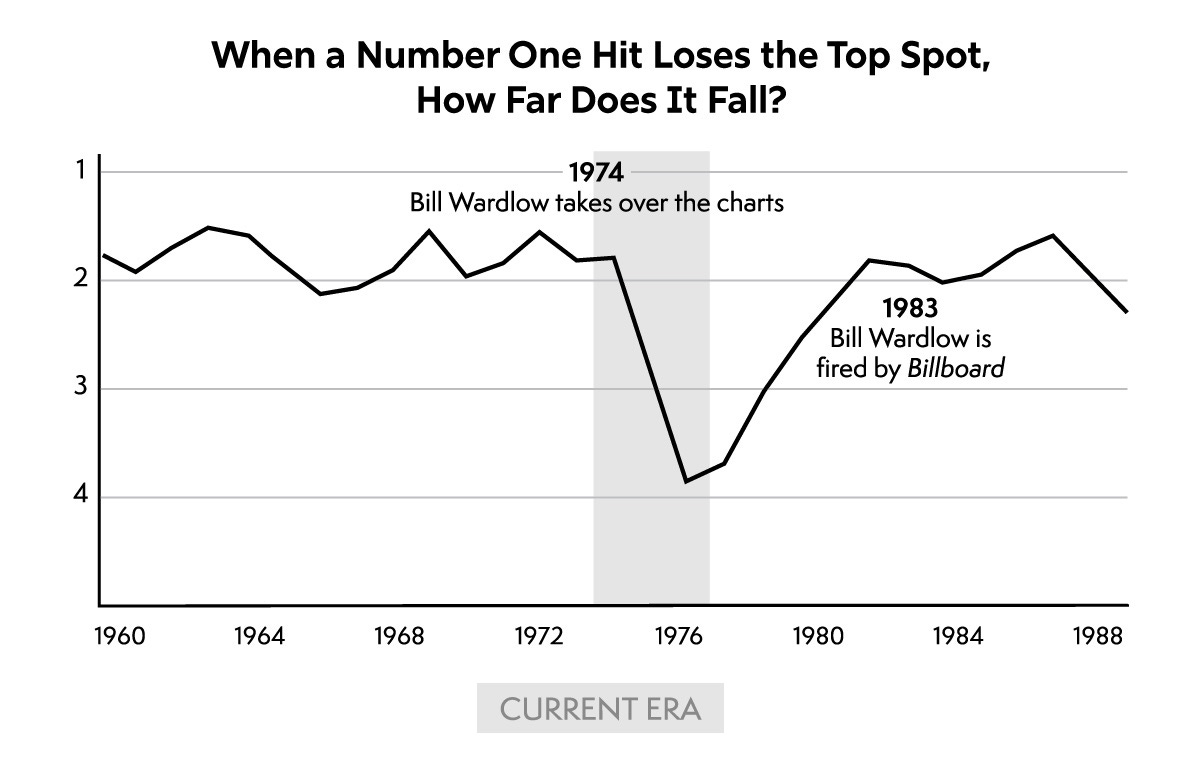

At the same time, when songs were losing the top spot, they were falling farther down the charts than ever before. For example, Andy Kim’s “Rock Me Gently” (September 28, 1974), a joyous record that you could mistake for the best of Neil Diamond, and Stevie Wonder’s “You Haven’t Done Nothin’” (November 2, 1974), a Richard-Nixon-protest-track, each fell from number one to number 12 in a single week. Similarly, Billy Preston’s soulful jam “Nothing From Nothing” (October 19, 1974) and Dionne Warwick and The Spinners duet “Then Came You” (October 26, 1974) fell from number one to number 15 in a single week. When you look at the average fall from number one, it becomes clear that these weren’t aberrations.

In Figure 5.2, you can see that from 1958 through most of 1974, when your average song lost the top spot, it was falling one to two slots. In this era, it was falling close to four slots before returning to the old rate of decline by the end of the decade. Something fishy was going on. And that something was Bill Wardlow.

In the book And Party Everyday: The Inside Story of Casablanca Records, here’s how Larry Harris, a cofounder of the famed label, describes Billboard chart creation during the Wardlow era: “For the past two years, I had had control over the Billboard charts and was able to significantly affect the positions of our records to help establish a perception that our company, Casablanca Records, and our artists . . . were the hottest in the music industry.” Later on, he goes so far as to say, “Eventually, I could walk into Bill’s office, tell him the position on the charts I felt a given album should have, and, lo and behold, there it would be.” If we can take Harris at his word—and the statistical anomalies we’ve discussed suggest that we can—why would Wardlow do this?

“Bill loved disco,” Harris wrote in his book. “Casablanca was disco . . . Bill wanted very much to be part of our scene, even going so far as to create a separate disco chart called National Disco Action Top 40.” In an interview with the AV Club about the book, Harris also claimed there was a sexual component. Wardlow, he says, was gay and wanted to ingratiate himself with the gay disco scene.

Of course, Harris was not the only person involved in this behavior. Quid pro quo arrangements remained common in the radio world. Did any involve Casey Kasem, the behemoth of the airwaves that we talked about at the beginning of this section? I haven’t found any evidence that Kasem and Billboard were in cahoots, but there was an incentive for the charts to shake out a certain way to make for better radio.

For example, when Carl Douglas’s “Kung Fu Fighting” (December 7, 1974) ranked number one during the week of December 14, 1974, John Lennon’s chart-topping “Whatever Gets You Thru the Night” (November 16, 1974) held onto the fortieth position for a second week on its way down the charts. Because Paul McCartney’s “Junior’s Farm,” Ringo Starr’s “Only You,” and George Harrison’s “Dark Horse” were also in the top 40 that week, it marked the only time each ex-Beatle had a simultaneous solo hit. Maybe Billboard did Kasem a favor for a good story. Anything is possible in the sketchy world of popular music.

This was an excerpt from Chris Dalla Riva’s forthcoming book, Uncharted Territory: What Numbers Tell Us about the Biggest Hit Songs and Ourselves. If you enjoyed it, you can pre-order a copy of the book today. And if you think you have a way for Chris to promote the book, please reach out via this form.

Good luck with the book, Chris.

As Ted Gioia always points out: it might very well have been corrupt, but at least the players in the game all benefited if kids listened to more new music.

As opposed to now, where Spotify's ideal customer is someone who subscribes but never listens. And since music companies make more money selling old music, they don't care about new artists either.

Glad I found you. I have been seemingly obsessed with Wardlow for decades - his time running the charts was my prime Top 40 listening period. Another thing that Wardlow did was push disco songs up the Hot 100 far higher than Cashbox and Record World did. Between the Fall of '76 and the Spring of '77 there were numerous examples of this. Two that interested me were "Spring Rain" by Silvetti, which literally made the Hot 100 top 40 twice (falling out then coming back in), while on Cashbox it peaked at 97 and never even made the Top 100 on Record World. The other is "N.Y., You Got Me Dancing" by the Andrea True Connection. This peaked at 27 on the Hot 100 but only got in the mid-80s on Cashbox and the mid-90s in Record World. Paul Haney of Record Research even used that later song as an extreme example when he was pushing the chart comparison book.