You Can Pre-Order My Book!

And I'm so excited for you to read it

7 years ago, I decided that I was going to listen to every number one hit. Along the way, I tracked an absurd amount of information about each song. Using that information, I wrote a data-driven history of popular music covering 1958 through today. It’s called Uncharted Territory: What Numbers Tell Us about the Biggest Hit Songs and Ourselves, and you can finally pre-order it!

Over the next few months, I am going to share excerpts from and insider information about the book. I’m also gearing up to do press about the book in the fall. If you have a podcast, newsletter, or publication that would like to promote Uncharted Territory, reach out to me here. I’m down for interviews, collaborations, or almost any type of promotion you can think of. No platform is too small!

But, for now, let’s turn to that excerpt. It comes from Chapter 10, where I cover November 9, 1996 to February 14, 2004. The only thing you need to know is that if a song is followed by a date (e.g., “No Scrubs” by TLC (April 10, 1999)), then that song was a number one hit and that was the date it topped the charts.

Mix a Little Bit of Ah Ah

An Excerpt from Chris Dalla Riva’s Uncharted Territory

Clive Campbell was a fledgling DJ in the Bronx in the early-1970s when he made a simple but powerful observation. Campbell, known as DJ Kool Herc, noticed that there were certain parts of songs, usually the rhythmic breaks, that partygoers reacted to more energetically than others. He realized that if he had two copies of a record and two turntables, he could extend those parts as long as he wanted to by starting one record at the beginning of the popular section as the other got to the end of it.

On August 11, 1973, Herc and his sister decided to throw a party at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue in the Bronx. Entry was $0.50 for men and $0.25 for women. Herc would be spinning tunes all night, and the profits would go toward his sister updating her wardrobe for the new school year.

The story handed down is that on that night DJ Kool Herc invented hip-hop. Is this lore true? According to research conducted by the PBS program History Detectives, the 1520 Sedgwick party did occur. But was hip-hop invented at the party? Not exactly. Like anything else, hip-hop developed over time. What can be said is that over the next few years Herc and his crew established many key elements of hip-hop. They built new music by sampling older records. They delivered spoken word, sometimes in the form of rhyme, over those samples. They shaped a new culture.

We spoke about some of hip-hop’s effects on lyrics in the last chapter. Now, I want to talk about how sampling inside and outside of hip-hop represented both a profound shift and continued history in music production and how it was impacted by the proliferation of digital sound.

A History of Musical Quotation

Instruments were invented to create music. Record players were invented to replay recordings of music. This seems so obvious that it isn’t worth stating, but it demonstrates how innovative the pioneers of sampling were. These people looked at a device meant to replay recorded music and decided that it could also be an instrument. This innovation didn’t begin in the Bronx of the 1970s with DJ Kool Herc and the rise of hip-hop, though. It went back further.

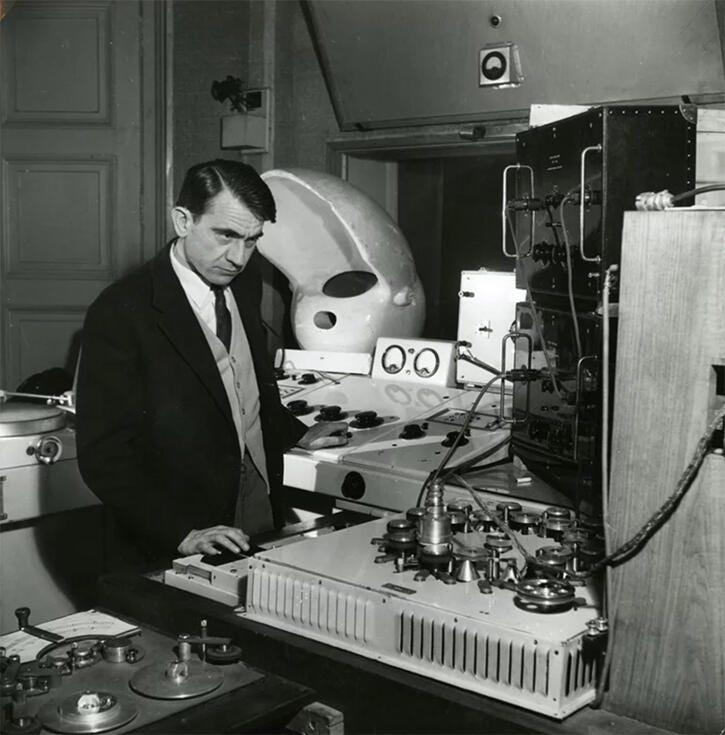

Though composers and critics began to imagine using previously recorded sounds to create new music at the beginning of the 20th century, it wasn’t until the 1940s that French musician Pierre Schaeffer realized many of these ideas via “musique concrète.” Schaeffer described the principles of musique concrète as follows: “Instead of notating musical ideas on paper … and entrusting their realization to well-known instruments, the question was to collect concrete [recorded] sounds … and to abstract the musical values they were potentially containing.” Schaeffer composed “Cinq études de bruits” in 1948, which was built by manipulating previously recorded sounds, just like hip-hop producers would do decades later.

This isn’t to suggest that the pioneers of hip-hop were influenced by musique concrète. In fact, musique concrète has a more direct lineage with the experimental of works of The Beatles (e.g., “Revolution 9”) and Frank Zappa (e.g., “The Return of the Son of Monster Magnet”) than that of hip-hop’s forefathers. It’s to say that though they are of a distinct descent, the techniques emerging in the Bronx in the 1970s were also being explored by many others, including the disco DJs down-the-road in Manhattan that we discussed in Chapter Five.

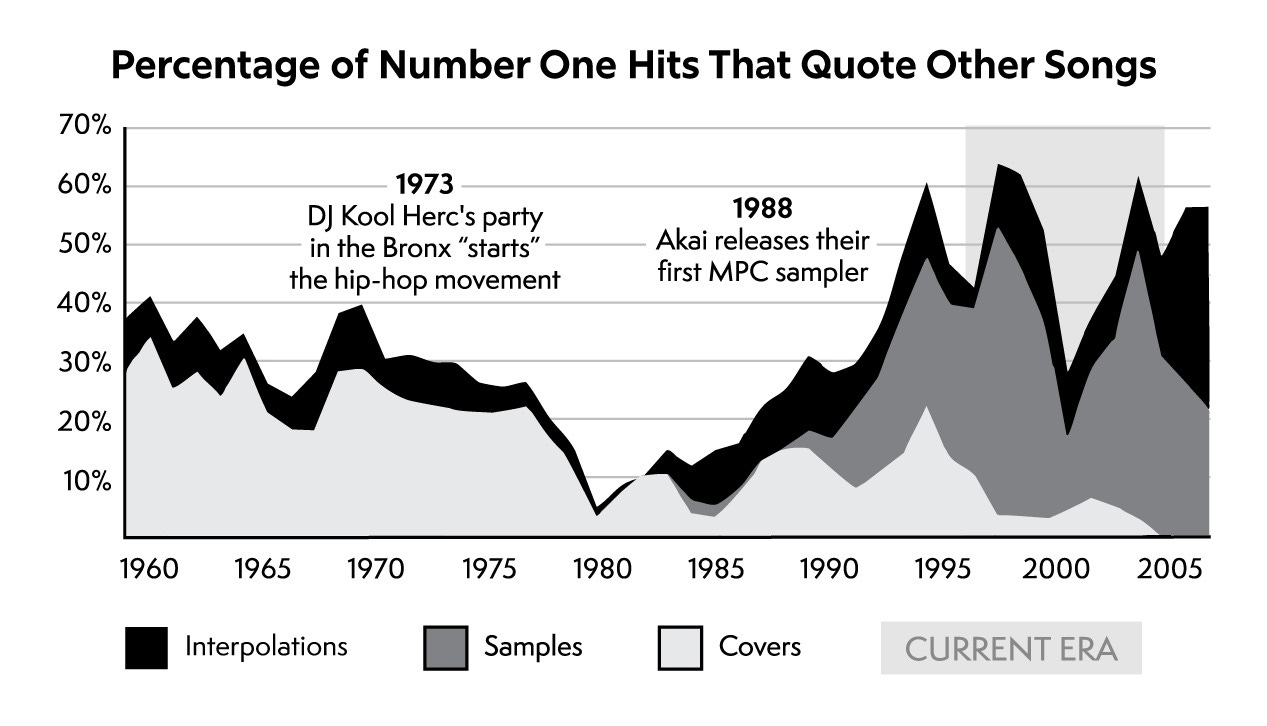

While repurposing existing recordings was an innovative, paradigm-shifting act, in a more abstract sense it fits with the evolution of other genre traditions. From the blues to country to jazz, songs have always been composed by quoting older works. We can see the evolution of these quotations through the number ones in Figure 10.5.

Along with samples, there are two other ways that artists can (clearly) base their works on older pieces: covers and interpolations. We discussed some of this in Chapter Four but let me jog your memory. A sample is when an artist reuses part of another recording in a new song. An interpolation, sometimes called a “sample replay,” is when an artist re-records part of an older work for a new song. And a cover is a recording of an entire song originally composed and recorded by others.

The cover saw a slow and steady decline at the top of the charts since the inception of the Hot 100. In the first era, 32% of number ones were covers. In this era, 3% were. That’s so few that I can list them: Monica’s “Angel of Mine” (February 13, 1999), Christina Aguilera’s “What a Girl Wants” (January 15, 2000), and Christina Aguilera, Lil Kim, Mýa, and Pink’s “Lady Marmalade” (June 2, 2001).

The death of the cover is related to the proliferation of recorded music that we discussed in Chapter One. As recordings became ubiquitous, listeners became used to specific productions of songs rather than the songs themselves. For example, though we associate the song “Hey Ya!” (December 13, 2003) with Outkast, the duo that recorded it, had it been released decades prior there would have been other competing versions of the song out at the same time. Nevertheless, the death of the cover did not lead to the death of musical quotes. Those quotes just appeared in different ways.

Interpolation: In the introduction of Aaliyah’s “Try Again” (June 17, 2000), Timbaland, the song’s producer, raps a piece of Eric B. and Rakim’s “I Know You Got Soul”.

Sampling: The Notorious B.I.G. raps over Herb Alpert’s instrumental “Rise” (October 20, 1979) on “Hypnotize” (May 3, 1997).

Interpolation & Sampling: Shaggy, who’d already interpolated War’s “Smile Happy” on his licentious “It Wasn’t Me” (February 3, 2001), teamed up with Ravon for “Angel” (March 31, 2001), a song that samples the guitar riff from the Steve Miller Band’s “The Joker” (January 12, 1974) and interpolates the chorus of “Angel in the Morning,” a song written by Chip Taylor.

While interpolation remained common throughout this era – 13% of number ones interpolated elements of other songs – it was the rise of sampling that represented the most notable way that artists were quoting older works. In total, 31% of number ones in this era contained a sample.

The rise of sampling was driven by the proliferation of affordable digital samplers. In the 2014 Ted Talk “How Sampling Transformed Music,” producer Mark Ronson said, “30 years ago you had the first digital samplers, and they changed everything overnight. All of a sudden, artists could sample from anything and everything that came before them, from a snare drum from the Funky Meters to a Ron Carter bassline [to] the theme to The Price Is Right.”

When compared to the sampling that DJ Kool Herc was doing in the early-1970s, digital samplers made sampling much easier. Let’s understand how digital samplers work and how their use is no less creative than writing songs on, say, a guitar or piano.

A Sampling of Sampling

When an artist samples another song, they take a snippet of an existing recording, alter it in some way, and then make a new song from it. When sampling pioneers were doing this, it involved physically altering the tape that music was recorded to. So, if you wanted to chop up a song into a sample, you had to physically snip the tape where the desired sample was. If you wanted to reverse it, you had to flip the tape over and play it backwards. If you wanted to splice it with another sample, you had to attach the tape that each was recorded on. As you’d imagine, this was a laborious, error-prone process.

Digital samplers changed this. Companies like Akai and Roland released devices that allowed artists to chop, edit, splice, process, and loop samples by clicking a few buttons. These devices thought of sampling a bit more generally than we’ve conceived of it thus far, though. In fact, they were descendants of the drum machines we discussed in Chapter Eight. But they had more flexibility. Yes, you could sample, say, “The Glow of Love” by Changes, like Janet Jackson did with Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis on “All for You” (April 14, 2001), but you could also sample things that weren’t necessarily associated with another song, like individual drum hits or horn stabs.

In Figure 10.6, you can see my Akai MPC digital sampler. The MPC was created in 1988 by Roger Linn in conjunction with the Akai, and it was built off much of Linn’s previous drum machine work that we discussed in Chapter Eight. The MPC takes your samples and maps them to each of the sixteen pads on the left. Then you can tap any of the pads to play the samples, sort of how you would play a traditional instrument. In fact, in the operator’s manual for the MPC3000, Linn wrote, “I like to think of the MPC3000 as the piano or violin of our time, and you as an MPC3000ist.” The MPC and its competitors helped artists create some fascinating work in this era.

Sometimes an artist would take a tiny musical snippet of an older song and turn it into something wildly different. For example, Monica, with producer Jermaine Dupri, chopped up a piece of Diana Ross’s sensual record “Love Hangover” (May 29, 1976) and turned it into “The First Night” (October 3, 1998), a song about sexual uncertainty.

On “Doo Wop (That Thing)” (November 14, 1998), Lauryn Hill sampled the ascending horn line from The 5th Dimension’s “Together Let’s Find Love.” In addition, BLACKstreet, with some help from Dr. Dre and Queen Pen, built their swaggering record “No Diggity” (November 9, 1996) around a sample of Bill Wither’s “Grandma’s Hands.”

But artists wouldn’t always sample the music from other tunes. Sometimes they’d cut up lyrical sections. “All I Have” by Jennifer Lopez and LL Cool J (February 8, 2003) uses a sped up vocal sample from Debra Laws’ song “Very Special.” “Mo Money Mo Problems” (August 30, 1997), released posthumously by The Notorious B.I.G., sampled the music and lyrics from Diana Ross’s “I’m Coming Out.”

“Mo Money Mo Problems” was produced by Sean Combs, sometimes known as Puff Daddy or Diddy. Bad Boy Records, founded by Combs, sent five records to number one in this era, almost all of which were produced by its founder. Despite the success, Combs was often criticized for liberally sampling from known hits. In 1999, Dr. Dre told Newsweek, “I respect Puffy as a businessman … But as a musician, he's really hurt the art form. Don't just throw something out there over somebody else’s beat.” The best example of Dre’s criticism is “I’ll Be Missing You” (June 14, 1997), a collaboration between Combs, Faith Evans, and 112.

“I’ll Be Missing You,” a song mourning the death of The Notorious B.I.G., samples the guitar riff from The Police’s massive hit “Every Breath You Take” (July 9, 1983), along with interpolating the chorus. Because of that, it feels like Combs is trying to cash in on nostalgia by making songs that quote hits from yesteryear.

Combs isn’t the only culprit of this. On “Getting’ Jiggy Wit It” (March 14, 1998), Will Smith ditched his longtime collaborator DJ Jazzy Jeff and teamed up with producers Poke and Tone to create a party starter centered around samples from Sister Sledge’s classic “He’s the Greatest Dancer” and the Bar-Kays’ deeper cut “Sang and Dance.” The next year, he took the same approach with a new set of collaborators on “Wild Wild West” (July 24, 1999), a song built around Stevie Wonder’s “I Wish” (January 22, 1977).

Given the popularity of these records, it’s clear that the public doesn’t hate sampling of this type. My friend Monica once told me that she loves the few seconds of uncertainty when you’re at a bar and can’t tell if they’re playing Stevie Nicks’s “Edge of Seventeen” or Destiny’s Child’s “Bootylicious” (August 4, 2001). The latter samples the well-known guitar riff of the former. My friend adores both.

Still, tracks like these are the ones that people will bring up when they characterize sampling as uncreative. And in this case, I’d agree with them. But they’re generalizing. Acclaimed sample-heavy albums – like Fear of a Black Planet by Public Enemy, 3 Feet High and Rising by De La Soul, Donuts by J Dilla, Since I Left You by The Avalanches, and Paul’s Boutique by The Beastie Boys – build their songs by manipulating snippets from unexpected, often obscure works to create something novel.

Big Boi, one half of Outkast, vocalized this same sentiment in a 1998 interview: “[W]e like to do creative sampling. We sample a horn riff or some kind of kick or snare … You never know where it came from cause we alter it so much to fit what we doing.” And he wasn’t exaggerating. Some online sleuths suggest that Outkast’s “Ms. Jackson” (February 17, 2001) samples the Brothers Johnson’s 1977 cover of Shuggie Otis’s “Strawberry Letter 23.” If it does, it’s unrecognizable.

For Outkast, Dr. Dre, and many others, sampling isn’t a cop out. It’s a creative act, as creative as picking up a guitar and writing a song. In fact, the way artists innovated with digital samplers in this era is akin to how guitar-slingers did the same in the 1960s. Both were using new technology to push their art further.

This was an excerpt from Chris Dalla Riva’s forthcoming book, Uncharted Territory: What Numbers Tell Us about the Biggest Hit Songs and Ourselves. If you enjoyed it, you can pre-order a copy of the book today. And if you think you have a way for Chris to promote the book, please reach out via this form.

Great chapter! Excited for the whole thing. Really appreciate your approach to the topic.

Wait is this the Stereogum series? That was lit!