Recorded Music is a Hoax

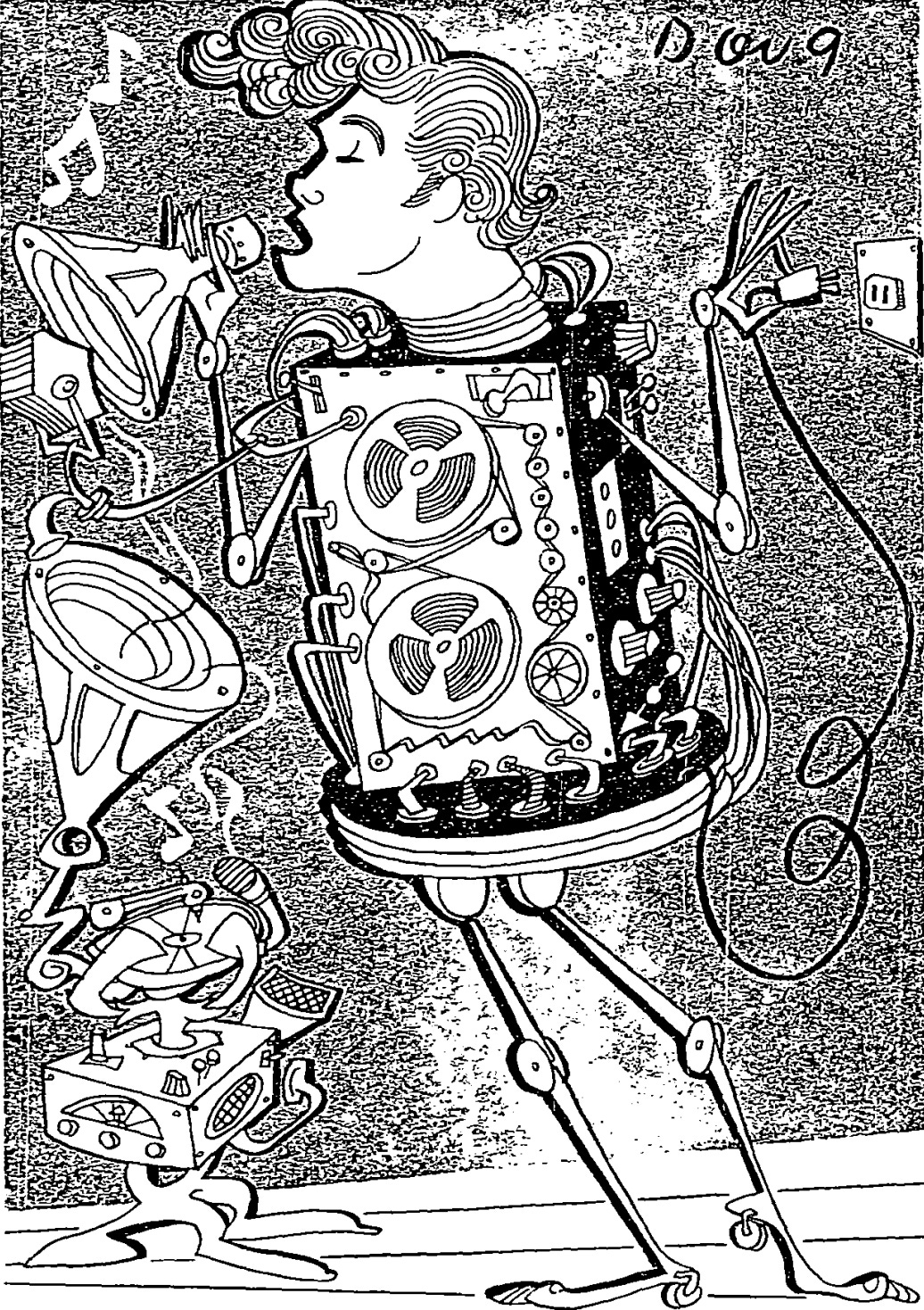

I've got bad news. If you enjoyed a musical recording in the last 100 years, you've been deceived.

I feel like this singer on TikTok is lying. I don’t think they are lying about their voice, though. I think they are lying about their concerts. They are always posting videos on stage, but I swear the videos are recorded in a warehouse with crowd noise piped in. Would this be a shock? Not really. The fundamental conceit of social media is dishonesty. You can portray yourself in any way you wish. But that’s when I realized something else: recorded music is largely built on dishonesty. Let’s talk about that.

As always, this newsletter is available to listen to on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and Substack. Additionally, our monthly mailbag is coming up. The mailbag allows me to answer YOUR questions. If you have a question, click the button below to ask it. If your question is selected, you will get a free premium subscription to this newsletter for a month. Premium subscribers get four additional newsletters each month.

The Lies of the Recording Studio

Here is a New York Times headline that I came across recently: “How No-Talent Singers Get Talent”. When do you think this headline was written? You could make a case for a number of different years. Maybe it was written in the 1980s about artists with lackluster vocals making it big on the back of flashy music videos. Maybe it was written in the 2000s about autotune-laden hits by Lil Wayne and Kanye West. Maybe it was written just a few weeks ago about artists experimenting with artificial intelligence technology. None of these suppositions would be correct, though.

This article was written for the June 21, 1959 edition of the New York Times by critic John S. Wilson. According to his obituary, Wilson “came to the New York Times in 1952 and was the newspaper's first critic covering popular music.” On this cloudy Sunday in 1959, he was upset about how “Recording techniques have become so ingenious that almost anyone can be a singer.” Wilson goes on:

A small, flat voice can be souped up by emphasizing the low frequencies and piping the result through an echo chamber. A slight speeding up of the recording tape can bring a brighter, happier sound to a naturally drab singer or clean the weariness out of a tired voice. Wrong notes can be snipped out of the tape and replaced by notes from other parts of the tape.

This article primarily fascinates me because if you made small edits to it, it could sound like it was written in any year. But it also fascinates me because Wilson seems unhappy with nearly every piece of technology that helps bring a recording to life.

He criticizes Elvis Presley’s voice for being “so doctored up with echoes that he sounded as though he were going to shake apart.”

He flags the holiday favorite “The Chipmunk Song” as exemplary of studio trickery because it was really Ross Bagdasarian’s voice “played double speed and blended by a process called overdubbing.”

He laments producers being able to “rearrange a recording after the performers have left the studio.”

He cites Whispering Jack Smith, a star of the 1920s, as representing the “move toward the synthetic singer” because Smith “found that the microphone eliminated the need for real vocal projection.”

For John S. Wilson, it seems, the entire enterprise of recorded music is suspect. Truth and honesty in music is conveyed when you have a group playing together. A recording should just capture the performance of that group with as little technological mediation as possible. Wilson is not alone in believing this. Take a trip through the history of recorded music and you will find musicians and fans continuously negotiating how recordings should sound and what they should represent.

In the early days of recording, the debate focused on if sound should be reproduced on discs or cylinders. Soon after, the debate shifted to the merits of acoustic versus electrical sound capture. Once electrical recording to discs became commonplace, the debate focused on if those discs should spin at 33 or 78 revolutions per minute. After that, the sonic thinkers of the day were concerned with stereophonic versus monophonic sound. More recently, the debate has focused on digital versus analog sound.

In Greg Milner’s tremendous book Perfecting Sound Forever: An Aural History of Recorded Music, he makes the point that each of these debates is litigating the same basic idea: what does it mean to “make a record of music — a representation of music — and declare it to be music itself?”

The history of recorded music is a history of answering this question, a history of deciding which methods are honest and which are deceptive. You may think the deception began with artificial intelligence or pitch correction or reverb or equalization, but it really began with a much more fundamental idea, namely the idea that if you don’t like how something sounds, you can record it again and again and again.

I’m not here to tell you that recording a second take of something is a mortal sin. I’m here to tell you that no matter what music you like, as long as it’s been recorded, you have been deceived.

If you like “Strawberry Fields Forever” by The Beatles, you have been deceived. The final recording is two takes at different speeds in different keys smashed together by the production genius of George Martin.

If you like Kiss’s classic album Alive!, you have been deceived. Basically, the entirety of an album purported to be recorded on stage was overdubbed in the studio.

If you like “Hungry Heart” by Bruce Springsteen, you have been deceived. The final recording was sped up to add excitement.

If you like when the prisoners hoot and holler at Johnny Cash singing the line “I shot a man in Reno just to watch him die” in his live rendition of “Folsom Prison Blues” at the Folsom State Prison, you have been deceived. That prisoner rowdiness was added after the fact.

So, is there some true, honest, ideal way to record music? Is there some perfect process that we should be using to capture sound properly? No. But I’ll take this idea even further. I’m skeptical that there is a true, honest, ideal way to make music even if you aren’t recording it. Let’s return back to one of John S. Wilson’s gripes to explain.

In his article, Wilson lamented the success of Whispering Jack Smith in the 1920s. Smith, Wilson claims, represented the “move toward the synthetic singer [because] the microphone eliminated the need for real vocal projection.” To understand what this means, compare Whispering Jack Smith to Enrico Caruso, maybe the most popular singer of the early 1900s.

Caruso’s booming, operatic voice exemplified vocal projection. But why did Caruso sing like this and not like the soft-spoken Whispering Jack Smith? It was largely for technological reasons. First, Caruso — born in 1873 — began his career before microphones were regularly used in concert. If he wanted to be heard, he had to sing loudly. Second, when Caruso first started recording, you had to sing into a giant horn. Again, if you were not loud, the horn couldn’t capture the sound.

To John S. Wilson, Enrico Caruso’s vocal style is the correct way to sing. Whispering Jack Smith’s vocal style is not just incorrect, but it is deceptive. He is using the new microphone technology that can pick up a larger range of sound to cover up the fact that he can’t really sing well.

In reality, Enrico Caruso’s vocal style is no more correct or true or honest than Whispering Jack Smith’s. From my perspective, Smith’s vocals are the beginning of a long line of vocalists that includes Frank Sinatra and Billie Eilish who used the recording studio to convey emotions that might not be possible to convey on a stage without any amplification. And that’s not just okay, but it’s what the studio is for.

Once you realize the breadth and depth of music that is created around the world, you realize that there isn’t some objectively correct way to make music. If the music moves you, if it moves the people around you, then you are making music as honestly as has been ever made. If you think otherwise, you’re going to miss out on a lot of great stuff.

A New One

"Obvious" by After

2024 - Indie Rock

Growing up, I was a musical snob, looking down on basically any artist who made music without guitar, bass, and drums. Of course, I came to my senses. But I mourn all of the music that I missed out because of those silly attitudes. If I hadn’t changed, I would have certainly missed out on “Obvious”, the latest single from the duo After.

Why would young Chris have been turned off by this warm crossover that harkens back to the 1990s? It’s built around guitars and wistful vocal harmonies. Those check the boxes of music that I considered legitimate. The problem would have arisen from the percussion. It was at least partially made with a drum machine. I found drum machines repellent. They were the pinnacle of musical falsehood. This is not true. Don’t be like me. You should vibe to drum machines, especially when they are backing nice melodies like the one you hear in “Obvious”.

An Old One

"Get Out Those Old Records" by Guy Lombardo & His Royal Canadians

1951 - Big Band

I sort of feel bad for ragging on John S. Wilson throughout the bulk of this piece. Not only is he no longer here to protect himself, but he was a respected jazz critic for decades. Plus, he insisted on freelancing for the New York Times rather than joining the staff because a staff position “would mean having to attend meetings.” A man who hates meetings is a man I respect. Regardless, Wilson’s piece is a good reminder that many of the arguments we have about music have been going on for a long time, albeit in slightly different forms.

But it’s not just our conversations about music that move in circles. It’s also the topics that we sing about. Take this Guy Lombardo song from 1951 called “Get Out Those Old Records” as an example. As the name suggests, this song sees Lombardo and his bandmates longing for the music of yore. Nostalgia, of course, is nothing new. But longing for “old” records when the music industry is barely 50 years old will always be funny to me.

Want more Chris? Check out this interactive piece that he worked on with The Pudding. It investigates how Rolling Stone’s top 500 albums have changed over the last 20 years and the underlying forces that shaped those changes.

Do you have a question for Chris? Send your burning musical question to his mailbag. If your question is selected, you get a free premium subscription to this newsletter for a month.

Oh boy. Lmao. Talk about a deep ol' rabbithole. I think when we talk about being "deceived", that's a "category error". It assumes that recorded music and live performance of music are the same thing, and they're not.

They're not,

They're not,

They're not.

I have to repeat this for emphasis, because too many smart people have either conflated the two, or thoughtlessly accept the conflation.

They are two different extensions of the same art form, and one should not be mistaken for the other. A record is literally that; a permanent "record" of an otherwise ephemeral artwork. The alleged "deceptions" arise solely from the tools and tactics the technicians use to satisfy the demands of such permanence; such that the process of the record's creation takes on a life of its own.

This should be a stipulation, not a revelation. And yet, many people (including very many on this app) continue to view the two separate experiences as from the same bag; or worse yet, view live performance as some "poorer brother" of recorded (and enhanced) performance. The question is, which one contains the "soul" of the artists' art? That depends upon the artist, and what they are expressing through it. Some express different facets through each; The Beatles + The Who being prime examples. And that should be cool too.

The problems begin when it ain't; and that's a habit of mind too many folks inside and outside the music business have adopted.

I'm probably saying all this shit wrong. But as a live musician who makes records bc he has to, who works for a guy who's pretty much the opposite; it's something I feel in my bones.

Live Music is one experience; a record is another.

Embrace each for what they are, and *only* what they are, and you'll never feel "deceived".

Man I love this piece. It resonates with thoughts I have every time I hit “undo” in Logic. There is no contemporary music without layers of something like…artifice. Thanks for saying this all so clearly.

Every time we hear a rock band with both a drum kit and a singer—and the singer is audible…we’re hearing something “unnatural.” Do most non-musicians really get that?