101 Things I Learned Listening to Every Number One Hit: Part 2

You pick up a few things when you listen to 1200 songs

Because my book Uncharted Territory: What Numbers Tell Us about the Biggest Hit Songs and Ourselves is out next week, I’ve been detailing an absurd number of facts that I learned while listening to every number one hit in history. If you missed Part 1, make sure to go check that out. And if you still haven’t grabbed a copy of my book, I would be honored if you ordered one. As a reminder if you send me proof of purchase before the release date, you get 6 months of a free premium membership to this newsletter!

101 Things I Learned Listening to Every Number One Hit: Part 2

By Chris Dalla Riva

The Rolling Stones’ “Ruby Tuesday” is certainly the only number one hit to inspire the name of a popular restaurant chain.

Speaking of The Rolling Stones, if you ever feel lost trying to figure out how to play one of their number one hits on guitar, your ears are not broken. Their instruments are often slightly out of tune. That’s part of the allure, though.

Also, for some reason The Rolling Stones’ “Paint It, Black” has a completely unnecessary comma in the title.

One of the great debates of the 1960s is whether The Beatles or The Rolling Stones were a better band. While I will die on the hill that it is The Beatles, I think the more fascinating way to contrast the groups is the song structure each would use. The Rolling Stones used the verse-chorus song form on 6 of 8 (75%) of their number ones. The Beatles only used that form on 6 of 20 (30%) of their number ones. They were more likely to use the AABA song form, the common song form in first half of the 20th century. I have a half-baked theory that The Rolling Stones were perceived as more dangerous because they were using a newer song form. More on this in Chapter 5 of my book.

While the AABA song form has largely fallen out of favor, if you want to talk about something that’s really fallen out of more favor, it is introductions in pop songs. And if you want to talk about something that’s really, really fallen out of favor, it is baritone spoken word introductions like you’d hear on something like The Manhattan’s “Kiss and Say Goodbye.” If I had my way, we’d bring all of this stuff back.

Though unheard of these days, there have been two number one hits about looking for love in the newspaper: Rupert Holmes’ “Escape (The Piña Colada Song)” and Honey Cone’s “Want Ads.”

Each time I bring up Honey Cone’s “Want Ads,” I’m compelled to say that it is the most underrated number one hit of all time.

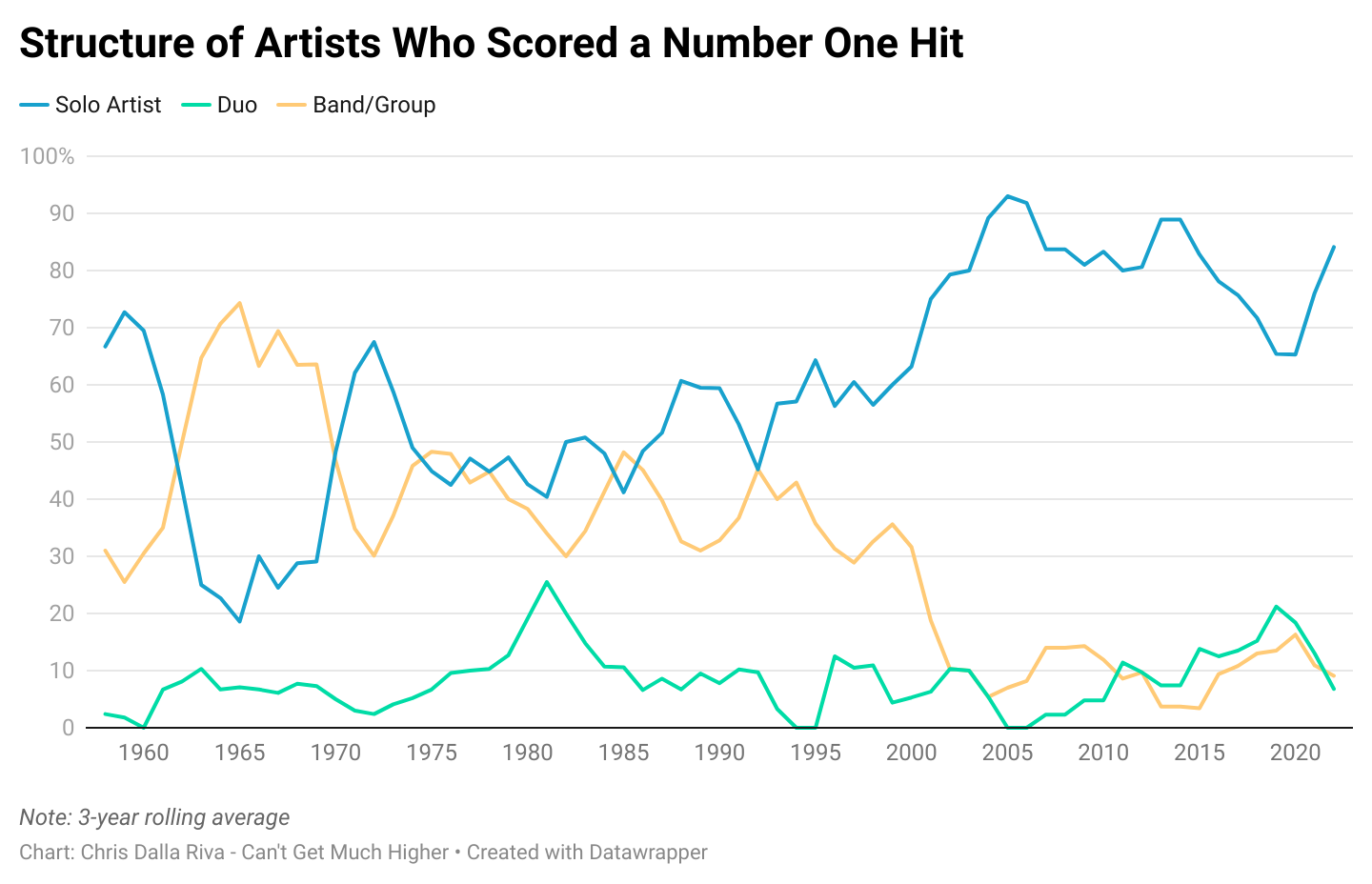

Honey Cone is also a relic of the past. Musical groups are much less common at the top of the charts than they once were. In fact, in most periods over the last few decades, between 70% and 90% of number one hits were by solo artists.

Though the large, large majority of number one hits are in 4/4 time, especially since 1970, there have actually been four that eschew that time signature over the last few years. Ariana Grande and Justin Bieber’s “Stuck With U,” Bruno Mars and Lady Gaga’s “Die with a Smile,” and Teddy Swims’ “Lose Control” are all in 6/8. Zach Bryan and Kacey Musgraves’ “I Remember Everything” switches between 7/4 and 4/4.

Speaking of the 7/4 to 4/4 switch, the Hues Corporation’s “Rock the Boat” also uses the same rhythmic trick. (I’m awaiting for someone to correct me that this isn’t actually 7/4 but a single bar of 3/4.)

If you want some other number ones with rhythmic weirdness, check out Three Dog Night’s “Mama Told Me (Not to Come),” John Denver’s “Thank God I’m a Country Boy,” Lionel Richie’s “Truly,” and The Beatles’ “All You Need is Love.”

A few years ago, I went very viral for pointing out how there are fewer key changes in pop songs these days. In fact, from July 2006 to December 2018 there were zero number one hits that utilized a key change. Since the publication of that article, there have been a handful of number ones with key changes (e.g., “Please Please Please” by Sabrina Carpenter). I am taking credit for this.

As I’ve noted repeatedly when talking about the decline of key changes, a key change does not necessarily connote musical sophistication. Most key changes on number one hits are just going up a half step or a whole step for the final chorus (e.g., “I Will Always Love You” by Whitney Houston)—not the most inventive compositional device. Sometimes it can be deployed with inventiveness, though. On The Beatles’ “Penny Lane,” the verses are in B major. Then the chorus shifts down a whole step to A major. But when the last chorus is doubled, McCartney goes back up to B major, thus returning to the original key but also giving the effect of the type of key change we’ve all heard a million times.

Though the average number one hit takes 2 or 3 songwriters to compose, there are actually a few with zero. Kind of. Since they are old folk numbers that evolved over a number of years, we don’t know who wrote The Animals’ “House of the Rising Sun” and The Highwaymen’s “Michael.”

Nevertheless, it took 30 people to write Travis Scott’s “SICKO MODE.”

That Travis Scott fact is slightly deceptive, though. Since the song contains a few samples, they have to credit all of the songwriters on that sampled music. But even if we remove the songwriters only listed for sample credits, “SICKO MODE” still has 12 songwriters, a record only matched by Cardi B’s “I Like It.”

As noted in Chapter 11 of my book, there was an explosion of songwriters credited on number one hits after 2000. If we look before 2000, the record is 9 for Kool & the Gang’s “Celebration.” Every member of the Gang got a credit on that one.

If we’re talking about the most accomplished songwriter of all time, it might be Charles C. Dawes. Along with winning the Nobel Peace Prize, Dawes served as the Vice President in the Clavin Coolidge administration. But before all that, Dawes wrote a short instrumental composition called “Melody in A.” When he died in 1951, songwriter Carl Sigman was inspired to set the melody to lyrics. As performed by Tommy Edwards, it topped the Billboard Hot 100 seven years later under the title “It’s All in the Game.”

Since Debbie Harry first decided to spit some rhymes on 1981’s “Rapture,” tossing a rap verse on a non-rap song is common way to try to expand a song’s audience on its way up the charts. Since 2000, 18% of number ones outside of the hip-hop universe have contained at least one rapped verse. These verses range from fun (e.g., “Heartbreaker” by Mariah Carey ft. Jay-Z) to head-scratching (e.g., “Black or White” by Michael Jackson ft. Bill Bottrell).

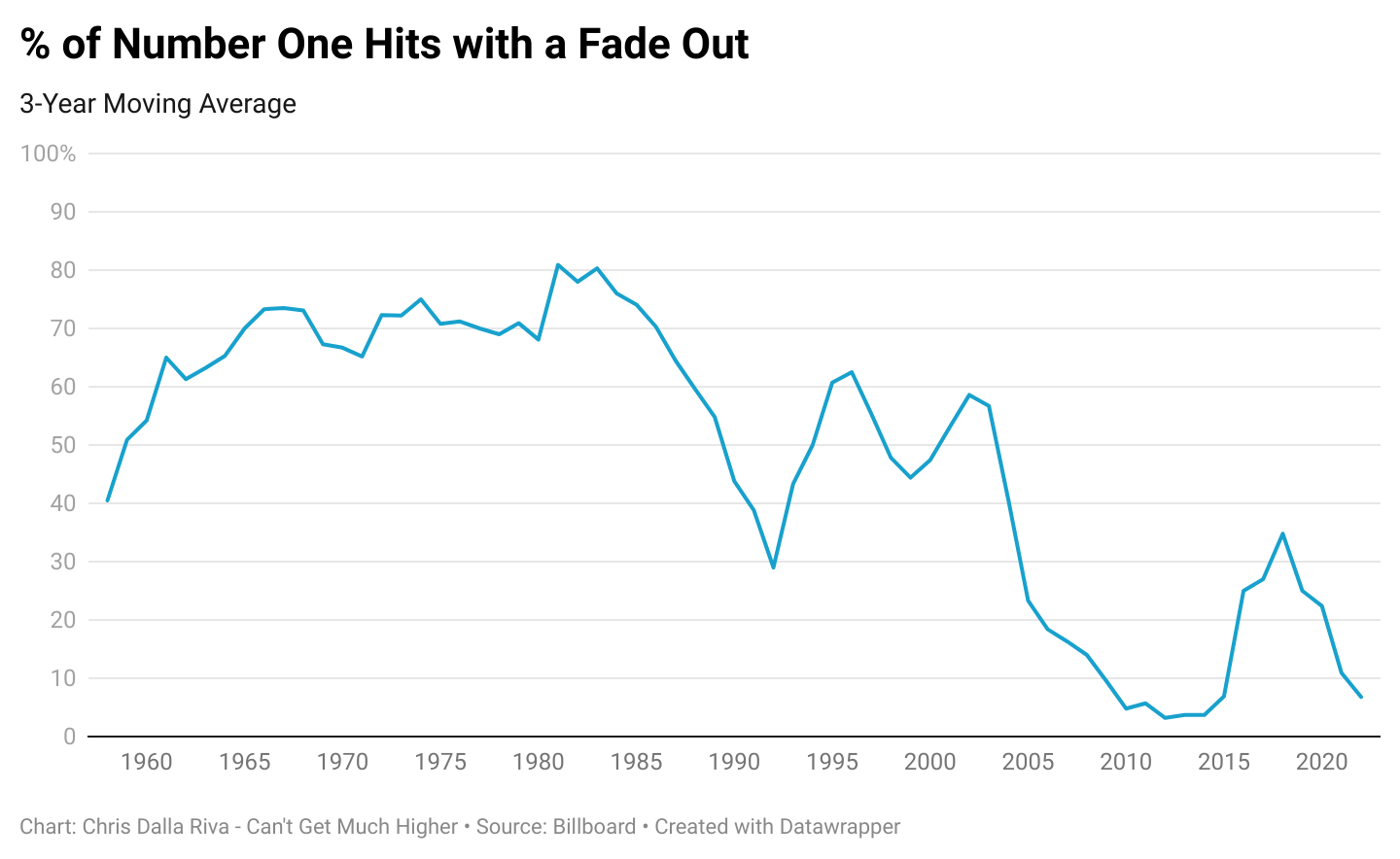

In Chapter 2 of my book, I explain and bemoan the popularity of fade outs as song endings in the 1960s. Lucky for me, the fade out, well, faded out during the 2000s. But it kind of resurged in the mid-2010s. I’m happy to report that it is dying again!

Other than a brief resurgence during the disco era, the instrumental number one hit effectively died around 1960. Over the last 40 years, all we’ve gotten are Jan Hammer’s “Miami Vice Theme” in 1985 and Baauer’s “Harlem Shake” in 2013. It’s time for vocalists to pipe down every once in a while!

On the topic of instrumentals, one of the biggest hits of the 1950s was Percy Faith’s “Theme from A Summer Place,” a song originally written for the film A Summer Place. But here’s an oddity. The original version had music and lyrics. Max Steiner wrote the music. Mack Discant wrote the lyrics. Even though Faith’s smash hit of the song was an instrumental, lyricist Mack Discant still collected royalties because the original version did have lyrics. (The world of musical publishing is filled with weirdness like this.)

Speaking of movies, sometimes songs inspire them. Bobbie Gentry’s “Ode to Billie Joe,” C.W. McCall’s “Convoy,” and Vicki Lawrence’s “The Night the Lights Went Out in Georgia” respectively inspired films released in 1976, 1978, and 1981, respectively.

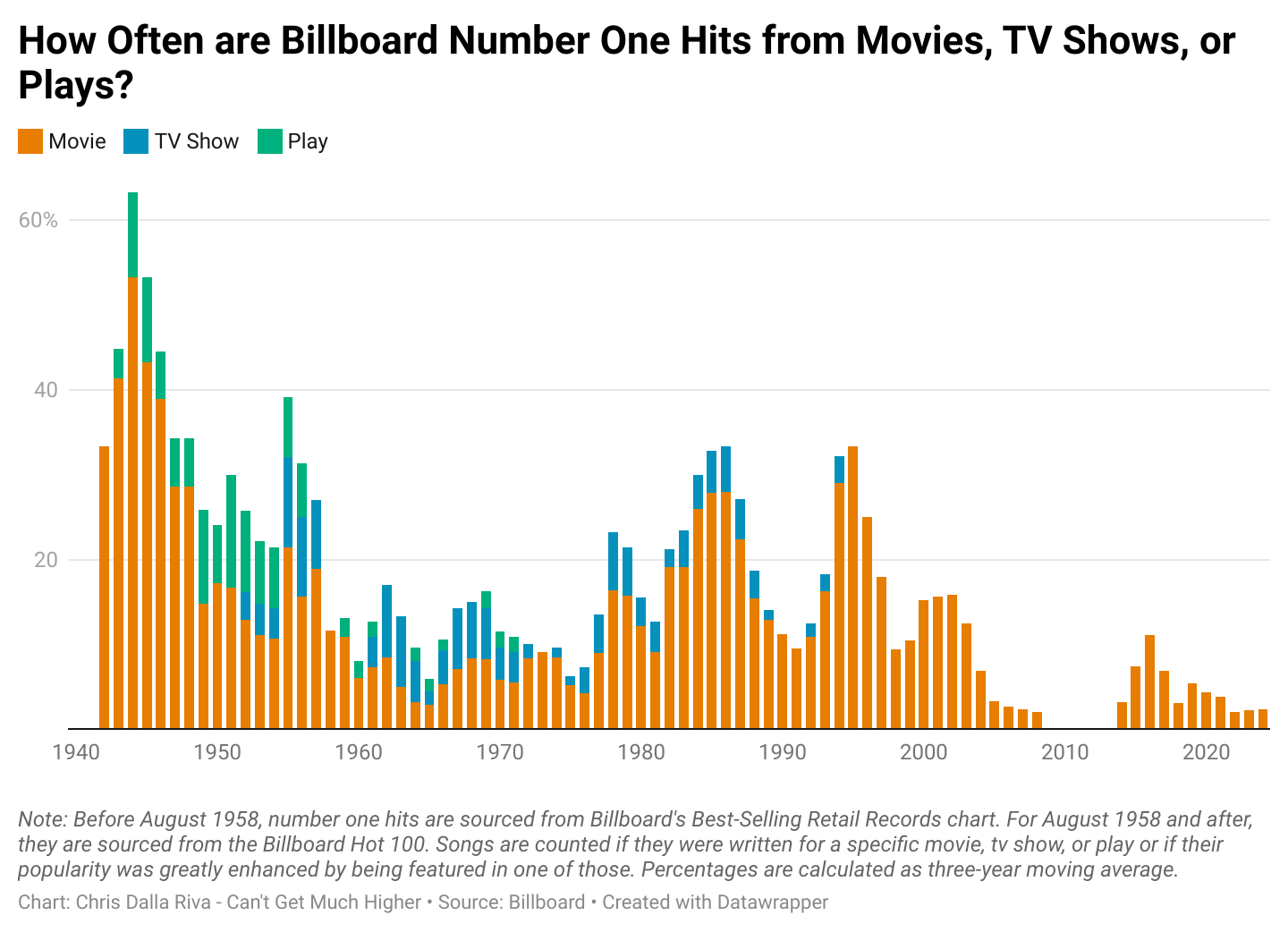

Of course, it’s much more common for movies to contain songs that soon become popular than for songs to inspire entire movies. While number one hits coming from Hollywood films are not as common as they once were, they still happen from time-to-time (e.g., “Shallow,” “We Don’t Talk About Bruno”).

Television shows, on the other hand, almost never spawn number one hits these days. The last number one hit to come from a television show was “How Do You Talk to an Angel,” the theme song of the short-lived 1992 musical drama The Heights.

Broadway is even less likely to spawn a number one than television. Since 1958, only four number one hits were originally written for a play: The Platters’ “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes” (Roberta), Bobby Darin’s “Mack the Knife” (The Threepenny Opera), Louis Armstrong’s “Hello, Dolly!” (Hello, Dolly!), and The 5th Dimension’s “Aquarius/Let the Sunshine In (The Flesh Failures)” (Hair).

While television is no longer a good way to score a hit song, it remains a good way to launch a career. Justin Timberlake, Miley Cyrus, Olivia Rodrigo, Sabrina Carpenter, Drake, Selena Gomez, Ariana Grande, and many others got their start on television shows.

48 of 50 US states have a dedicated state song. Interestingly, there are two songwriters to have composed state songs for two states. Stephen Foster wrote both Kentucky’s state song (i.e., “My Old Kentucky Home”) and Florida’s (i.e., “Old Folks at Home (Swanee River)”). John Denver—the man behind four number ones—wrote both Colorado’s state song (i.e., “Rocky Mountain High”) and West Virginia’s (i.e., “Take Me Home, Country Roads”).

The two states without state songs are Maryland and New Jersey. Maryland had one for decades but got rid of it in 2021 as an outdated “relic of the confederacy.” New Jersey—my home state—has never had one, though. We briefly tried to adopt Bruce Springsteen’s “Born to Run” as a state song of in the 1980s, but the resolution died in the state senate.

Sure, Bruce Springsteen has had a ton of success, but the rejection of his song as a state song is not his only failure. He also never had a number one hit. The closest he came was “Dancing in the Dark” peaking at number two in 1984. It got stuck by Prince’s “When Doves Cry,” a worthy adversary.

Springsteen did write a number one hit, though. Manfred Mann’s Earth Band topped the charts with a cover of his “Blinded By the Light.” That gives Springsteen another unfortunate honor. Along with Bob Dylan, Randy Newman, and a handful of other artists, he is part of a small group of musicians to write a number one hit but only perform a number two hit.

Speaking of number two hits, Creedence Clearwater Revival has the most number two hits without ever getting to number one. They made it to the runner up spot seven times without getting over the final hump.

Long dead classical composers occasionally impact the top of the charts. In 1972, Neil Diamond adapted a Mozart melody on “Song Sung Blue.” Four years later, Walter Murphy turned Beethoven into a disco star on “A Fifth of Beethoven.”

Beethoven wasn’t the only legend to get caught up in the disco craze. Frank Sinatra did too. His “Night and Day” was remixed with a dance beat in 1977.

The Star Wars theme song also got a disco makeover, so people really couldn’t control themselves in the late-1970s.

Speaking of the 1970s, the first song performed on Saturday Night Live was Billy Preston’s number one hit “Nothing From Nothing.”

My one friend that I listened to every number one song with would often joke that 1970s soft rock was born when Johnny Rivers topped the charts with “Poor Side of Town” in 1966.

The longest number one hit has changed periodically. For about 8 years, it was Marty Stevens’ “El Paso” (1960). Then “Hey Jude” took over (1968). Don McLean jumped ahead when “American Pie” topped the charts at 8.5 minutes (1972). That record proved quite durable until Taylor Swift’s 10-minute “All Too Well” got to number one in 2021.

Despite that, the shortest number one has remained even more formidable. Clocking in at 1:36, Maurice Williams’ 1960 hit “Stay” has held the record for 65 years. The closest anyone has come in recent memory is Lil Nas X with “MONTERO (Call Me By Your Name).” Running at 2:17, it is 42% longer.

Between Megan Thee Stallion’s “Hiss” and the Kendrick-Drake battle, 2024 was packed with diss tracks. The lyrical diss is not new, though, even at the top of the charts. In 1973, Eddie Kendricks took a stab at his former Temptations bandmates in “Keep on Truckin’” (i.e., “Diesel-powered straight to you, I’m truckin’ / In old Temptation’s rain, I’m duckin’”). In 2006, Timbaland fired a diss at his former production buddy Scott Storch on “Give It To Me” (i.e., “I’m a real producer and you just a piano man / Your songs don’t top the charts, I heard ‘em, I’m not a fan”).

One of my guiding principles is that if people like a song for decades, then we should probably consider that song a “good song.” This has (sadly) forced me to admit that Bon Jovi has some good songs.

But if you were to ask me what the greatest number one hit in history was, I’m not sure I could give a firm answer. I would be able to tell you that it was probably written in Detroit or by a Swede, though.

Thanks for reading. If you enjoy my work, please consider ordering a copy of my forthcoming book Uncharted Territory: What Numbers Tell Us about the Biggest Hit Songs and Ourselves. It’s a data-driven history of popular music that follows my journey listening to every number one hit from 1958 to 2025.

#81 reminds me of the now pretty well-known trivial fact that Gene Roddenberyy wrote (terrible and never performed) lyrics for the original Star Trek theme specifically to make sure he got a cut of the royalties.

Margaritaville is another chain but alas only hit #8