A Conversation with Me

Conducted by the writer Gordon Glasgow

If you’re familiar with this newsletter, you’ll know that I interview people around the music world twice a month. I’ve spoken with everyone from up-and-coming artists and hit songwriters to notable critics and Broadway stars. But when Gordon Glasgow agreed to interview me about my forthcoming book Uncharted Territory: What Numbers Tell Us about the Biggest Hit Songs and Ourselves for his insightful newsletter 12 Questions, I thought it would be fun to also circulate our conversation here.

Given that I inject myself into many of my newsletters, you’re probably at least a bit familiar with who I am. But Glasgow’s questions were so penetrating that I thought people here would find them valuable. How many other people are going to ask you about the evolution of concerts and your belief in God in 45 minutes? If you enjoy the interview, consider ordering a copy of my book.

Gordon Glasgow: How did your book come about?

Chris Dalla Riva: Years ago, I decided that I was going to listen to every number one hit mostly because I played music and wanted to improve as a songwriter. But my day job involved working with data, so I started collecting information about each song. I noticed some trends, wrote about them, and then sent it off to an old professor that I had in college. He said that it was good, and I should keep at it.

And I did. For years. It takes a long time to listen to every number one hit in history. But eventually I realized I had the makings of a book. The problem was that I’d never published a word of my writing anywhere. So, I started posting incessantly online to build an audience. Eventually, a former writer from Billboard saw a TikTok that I had made. He put me in touch with his editor at Rowman & Littlefield, who was interested in my idea. Rowman & Littlefield got purchased by Bloomsbury, so they are ultimately who is putting the book out. It was a good combination of pluck and luck.

Once you got the deal, did you have to write most of the book?

No. I’d already written 11 chapters. I thought there were going to be 12, so I told myself that I wouldn’t write the 12th until I signed a book deal. Then I signed the deal, and they asked for two more. So, I spent about 8 weeks writing the last two chapters and editing the rest of the manuscript.

Putting all data aside for a second, what were some of your personal favorite songs after listening to so many?

The fun thing about listening to every 65 years of number one hits is that you get to hear the good, the bad, and the ugly. Many of the great number ones are stuff that people are already aware of because they’ve stood the test of time. I still think “I Want You Back” by The Jackson 5 might be the most perfect pop song ever recorded. It’s got a great groove. You’ve got 11-year-old Michael Jackson singing like he’s from another planet. It just holds up so well. “My Girl” by The Temptations also comes to mind.

Were there any number ones in a foreign language?

Yup. Actually, the second song to ever top the Hot 100—Domenico Modugno’s “Nel Blu Dipinto di Blu”—is sung in Italian. That might make you think that lots of number ones over the years would be sung outside of English, but that’s not the case. Over 98% of number ones in history are completely in English.

But there have been number ones in Korean. There’s been one in German. There’s been one in French. There have been at least a handful with at least parts sung in Spanish.

Much of that Spanish is pretty recent, right?

Yes. Latin music really started to crossover in the US in the 1990s. Think Ricky Martin’s “La Vida Loca” and Los Del Rio’s “Macarena.” But in the 2010s, Spanish-language music has become even more popular in the US. The success of “Despacito” is usually marked as the big bang moment for the recent explosion.

Why do you think Latin music has done so well in the US in the last decade?

Beyond the fact that it’s fun to listen to, I think two factors play a role. First, demographics are always part of the equation. There is a large amount of people hailing from Spanish-speaking countries now living in the US. This is similar to how you saw a generation of Italian singers—albeit, often not singing in Italian—crossover in the US in the 1950s as Italian immigrants and their offspring began to represent a large chunk of the population.

At the same time, some of it is technological. Will Page and I have explored a phenomenon called “glocalization.” In short, distribution used to be very expensive in the past. To take advantage of economies of scale, labels would ship, say, a Madonna record all around the globe. The internet has driven distribution costs near zero. Now, you no longer have to rely on a label shipping Spanish-language music into the US. Just boot up your computer, and it’s there. The playing field has been leveled in some sense.

I’m fascinated by the subtitle of your book: “What Numbers Tell Us about the Biggest hit Songs and Ourselves.” What do numbers tell us about those things, and how have the things they tell us changed from previous eras?

Good question. Numbers allow us to check if our intuition is correct. Of course, not everything is measurable, especially in the world of music. But there are many things that lend themselves to quantification. Here’s a good example.

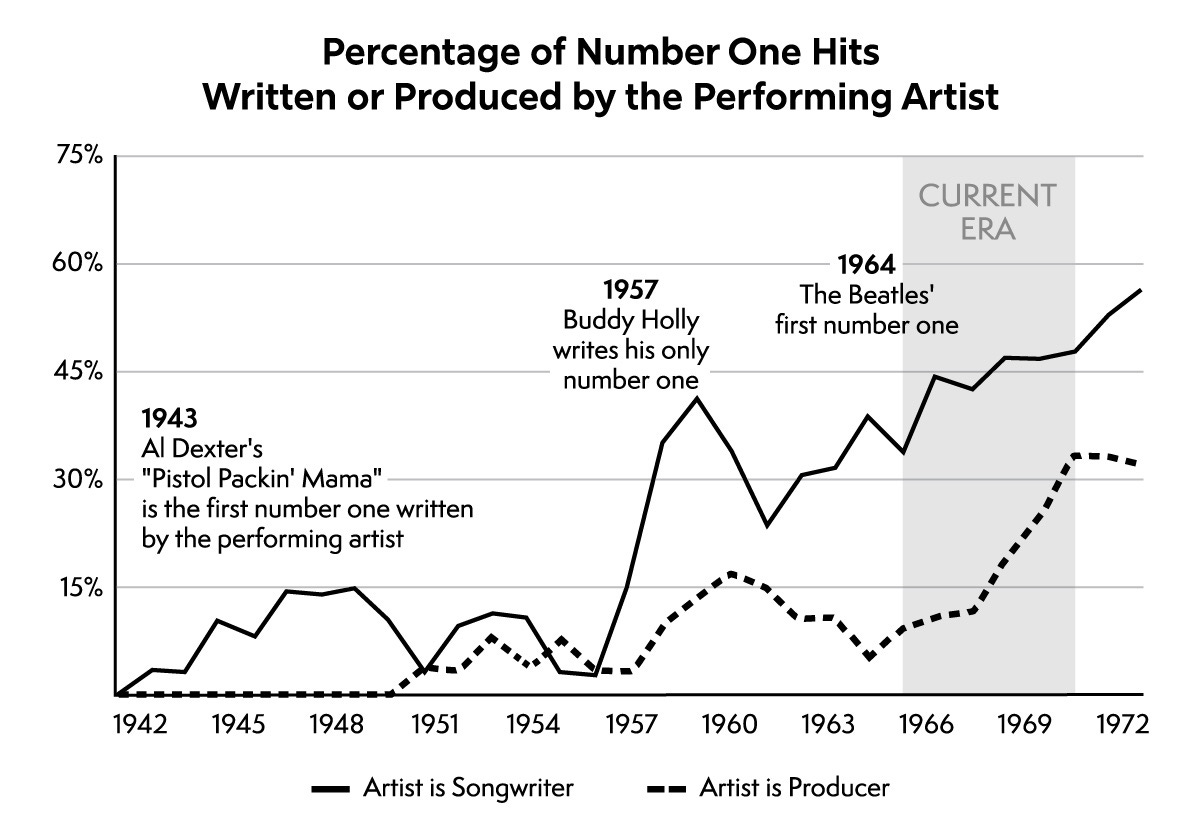

One of the common stories of the 1960s is that once The Beatles and Bob Dylan started composing their own songs, every other artist felt the need to do so to be taken seriously. Before that, pop stars did not compose their own music. The Beatles and Bob Dylan certainly influenced other artists to write their own stuff, but we can check this. Just take a sample of popular songs over time and look up who the songwriters were.

What I note in Chapter 3 of my book is that there was an explosion in artists writing their own work in the decade before The Beatles landed in the US. In short, the Fab Four was influential of this trend, but they were part of a much longer history. Throughout the book, I use data to see if our intuitions hold up to statistical scrutiny.

What other examples come to mind?

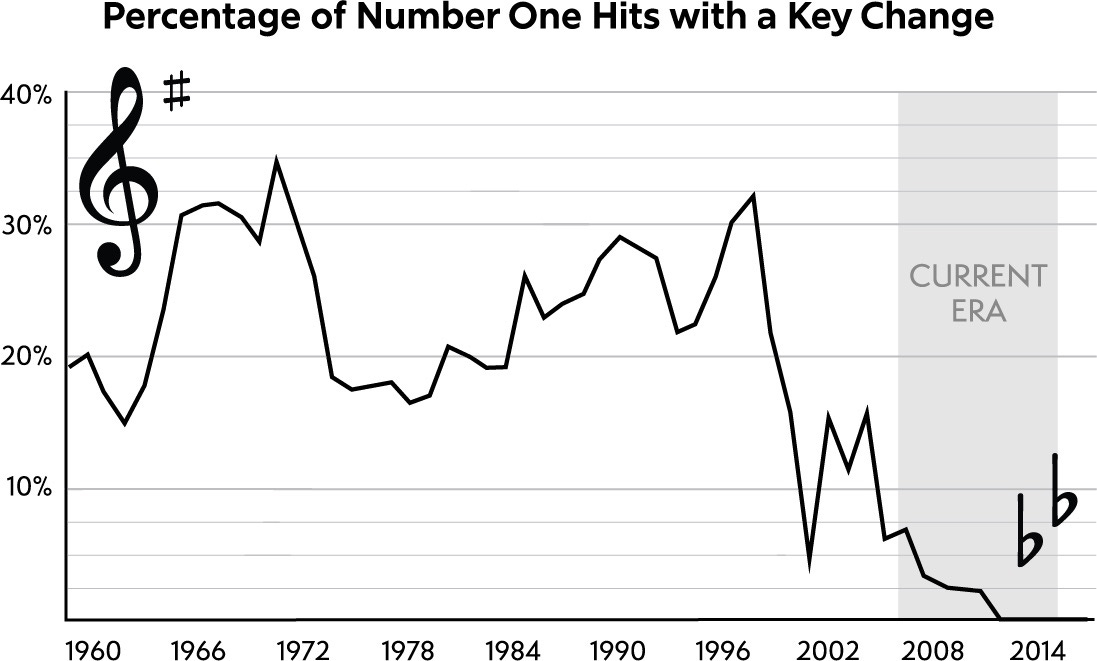

I’ve spoken about this before but key changes. While I was listening, my ears told me that around the turn of the millennium fewer artists were employing key changes in their hits. Rather than trusting my gut, I checked. I figured out the key to every number one hit and plotted songs with key changes. My intuition was correct. Key changes became a thing of the past in the 2000s. I write about that in Chapter 11.

What are some of the difficulties in articulating what music does to you?

I open the book with one of my favorite quotes: “Writing about music is like dancing about architecture.” I like this quote because music is hard to describe. I could write pages about a song and not capture any of the feelings you’d get from hearing the first second. I implore people to listen to songs as they read my book because songs are meant to be heard.

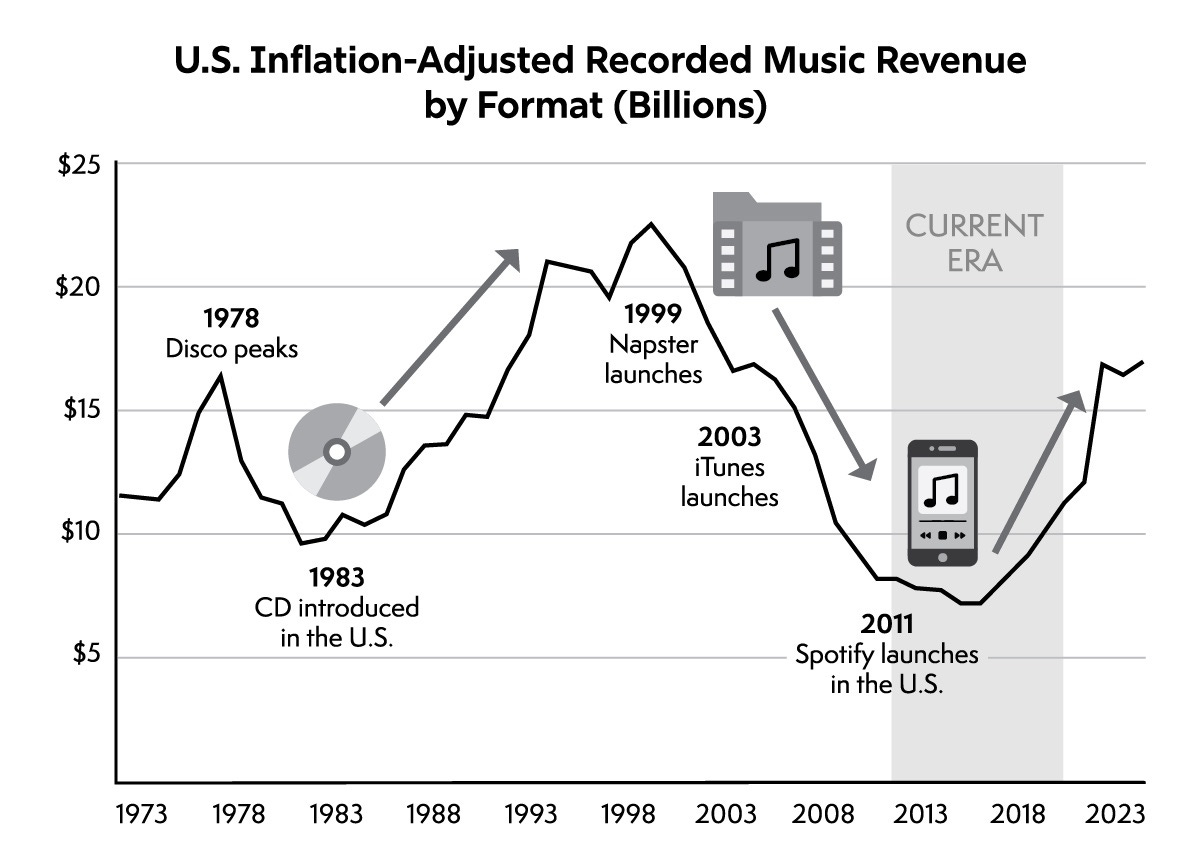

Just a moment ago, you mentioned how the internet changed the way we distribute music. Has technology, like Spotify, changed the type of music and the type of people that become successful?

One of the key themes of the book is that musical evolution is often downstream of technological innovation. Let me give you an older example. Before the microphone was invented, you had to project if you wanted to be heard. This influenced how people sang. Even when the first recording devices were created, quiet sounds could not be captured clearly. Again, this meant that singers had to sing loudly. And that’s the vocal style you associate with the beginning of the 20th century.

Then in the 1930s and 1940s, microphones become much better. They could pick up a wider range of sounds with great clarity. Suddenly, the soft croon of Frank Sinatra and Bing Crosby—a vocal style that wouldn’t have worked two decades before—becomes popular.

I don’t believe that technology is deterministic of art, but it certainly influences it. And we see this repeatedly over the decades. Vinyl records impact the music that is popular. MTV impacts the music that is popular. TikTok impacts the music that is popular. Technology is always there shaping things, sometimes unexpectedly.

What about Auto-Tune?

Auto-Tune is one specific product that does pitch correction. Another popular competitor is Melodyne. That aside, Auto-Tune fundamentally changed how we process and listen to the voice. I talk about this a bit in Chapter 10 of my book, Auto-Tune was initially just used to nudge notes that were slightly off pitch.

Then Cher released “Believe” in the late 1990s and changed everything. “Believe” used Auto-Tune as a vocal effect more than something to fix mistakes. In the next few decades, everyone from T-Pain to Kanye West was pushing Auto-Tune to its limits in their art. Ultimately, it’s a good example of how technology and art interact. Technology enables something and then artists push it as they follow their muse.

Did Kanye West’s 808s & Heartbreak change rap forever?

I try not to speak about “forevers,” especially in the world of popular music, but it certainly had a huge impact on hip-hop. The 2010s were dominated by artists who had melodies as strong as their raps. Drake is probably the best example of this. I think he lives in the wake of that album.

Were there any trends that you came across that you couldn’t relate to?

Listening to 65 years of number one hits certainly opened my mind to many styles I didn’t think that I liked. Still, there has been a strain of country music popular in the last decade that I really don’t like. It takes contemporary rap production and pairs it with corny country imagery. Think Morgan Wallen, Jelly Roll, and even Post Malone. I can see where these artists are coming from, but the music does nothing for me.

So, what are your roots? Do you love the Great American Songbook? Do you like sounds that are found in New Jersey, the place you are from? What drove you to want to tell this story?

I grew up listening to a ton of classic rock and pop punk bands of the 2000s.

Can you give me some names?

Sure. AC/DC was one of my first musical loves. I’m a big fan of Bruce Springsteen. Led Zeppelin. The Beatles. And, like I said, I also enjoyed some of the pop punk that was big when I was growing up. Think Simple Plan and Bowling for Soup.

By the time I went to college, my musical mind opened a bit more. I got more into hip-hop, especially the music of Kanye West. More recently, I’ve been enamored with many of the women who have reshaped popular music, like Lorde, Chappell Roan, and Olivia Rodrigo.

Is there one band or artist you go back to more than anyone else?

I’m pretty certain I’ve listened to Bob Dylan, The Beatles, and Bruce Springsteen more than any other artist.

Are you excited for the Springsteen movie?

I'll definitely go see it. I feel like most biopics are a little bit silly. They all sort of hit the same points, but the Bob Dylan one was pretty good earlier this year. I’ll be in the movie theater to support Bruce even if the movie stinks. I don’t have high hopes, though. [NOTE: After this interview, I saw the movie and really enjoyed it!]

Do you listen to music while you write?

I struggle to process words when listening to music. So, I usually write in silence. Funny enough, if I’m working with data in a spreadsheet, I love listening to music. For some reason, the music doesn’t interfere with my brain in that process.

When did you decide to spend more time pursuing your writing?

I’ve always enjoyed writing, but as I noted earlier, I had never published anything when I started writing this book. That said, I’ve never been shy about sharing creative projects publicly. In high school, I would hand out CDs with music I made. Writing is just another iteration of that.

Is it your goal to be a full-time writer? Or do you love what you do with data on a daily basis?

It would be cool to write full-time. I do really enjoy my job, though. I like working in the music industry. I think it gives me a different perspective compared to an outsider. If I could write full-time, I guess I’d do it, but I like living in both worlds for now.

When you write, who do you imagine you are speaking to?

When I was in college, I remember sitting around with my friends playfully arguing about a million things related to music and sports. When I’m writing, I imagine I’m addressing a room like that. I want to be conversational, convincing, and somewhat humorous.

Do you struggle writing about specific topics?

There are many times throughout my book where I write about race and gender. My personal perspective will be relatively limited on those topics given my demographic background, so I am always extra carefully when writing about them.

Are race and gender a key part to your book?

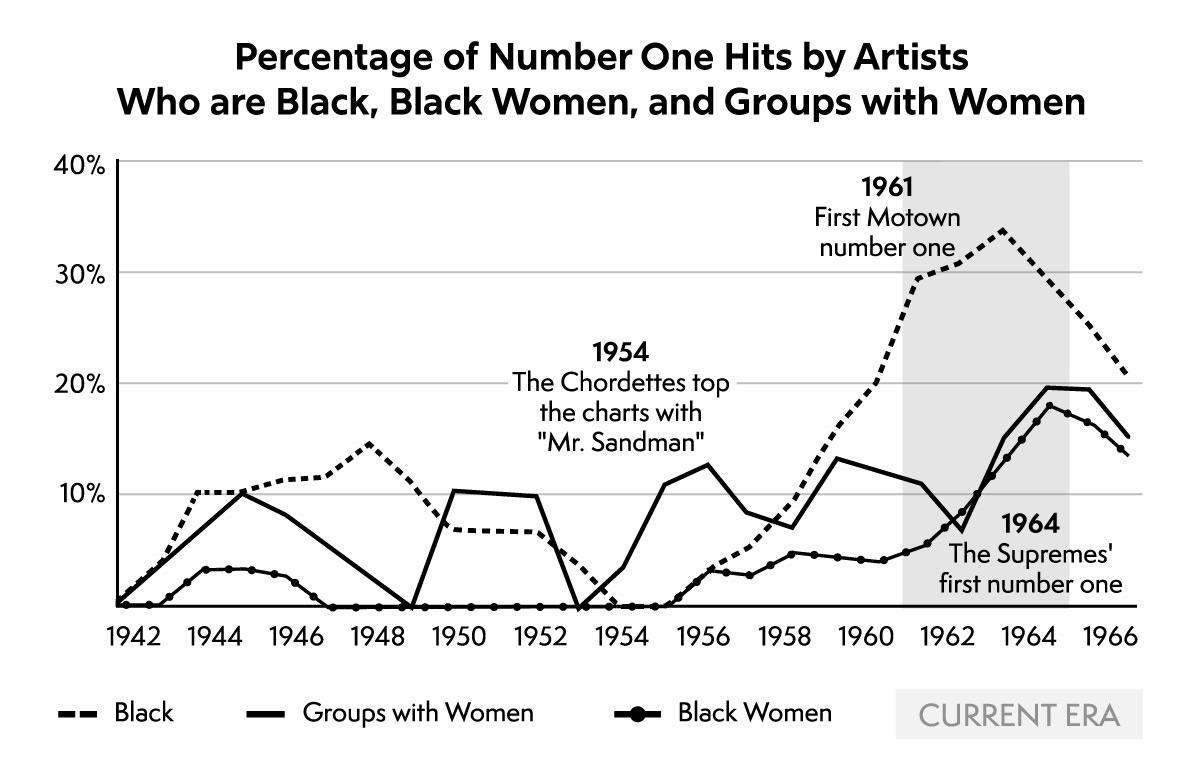

It’s not all about that, but I think it is a key theme because you can’t really tell the history of popular music without talking about the evolution of race and gender. For example, in the 1960s, I talk about the rise of Black artists on the charts as Motown becomes more popular. When talking about the history of R&B, I discuss how the name of the genre was initially “race records,” which effectively just meant music made by Black people. It was Jerry Wexler at Billboard who eventually decided the name was distasteful and that the magazine should use “rhythm & blues” or “R&B” as a term. Race, gender, and music are all intimately wrapped together in America.

How do you define “popular music”? We live in a weird time where so many fan bases feel siloed from one another.

You’re right. Historically, popularity just referred to what people were buying and what radio was playing. Because of that—and especially because of radio—you could walk up to someone on the street and have the same perspective on what was popular. So, for a long time, that’s what popular music meant. It was just what the biggest cohort of people were familiar with.

At this point, it is harder to define. Streaming services make all music available at the same time, and algorithms can push people to listen to only one little slice of that music. Of course, these ideas existed in the past, but I think they are more prevalent now. Occasionally, we still have artists crossover to the point where everyone is aware of them. The current quintessential example of that is Taylor Swift.

What are the aesthetics of an “earworm”?

I’ve always like the term “earworm” because it evokes a vivid image of something crawling around in your brain. And that’s what an earworm is. It’s something you can’t get out of your head. It’s there when you wake up. It’s there when you’re in the shower. I think that’s all that matters.

Is there a recipe for that? Or, is it just something natural that people know how to do?

Over short stretches of time, the most popular songs follow similar structures and sonic trends. In that sense, there is a recipe. Tremendously weird songs seldom reach mass appeal. But those are just broad guide posts. There isn’t one way to write a hit song.

Do you think artists are in a better place financially today than they were in the past? Or, do tech intermediaries create more problems than they are worth?

I’m biased because I work for a streaming service, but I think the world now is better for artists because they have a lot more information and control. You can build an audience and distribute your music without a record contract in a way that was very hard in the past.

There are certainly cons, though. The margins on CDs were insane. You didn’t have to sell many to make a substantial profit. Now, you need millions of streams to sustain yourself. I do think people who aren’t raking in millions of streams today overstate how many CDs they would be selling if the old world existed, though.

If I got 2 million streams on Spotify, how much money would I make?

I can’t speak to that specifically. The economics for how streaming pays are a bit strange. In short, there is a huge pool of advertising and subscription money. You then get paid your fraction of that money based on streams. So, imagine there were 10 million streams across the platform. Your 2 million streams would represent 20% of all streams. Assuming you are an independent artist working with a publisher, you’d collect 20% of revenues, less Spotify’s cut.

How do labels strategize to meet the demands of streaming? Or, rather, are they strategizing?

Much of their business model is built around this question. The strategy has changed, though. In the 1970s and 1980s, Clive Davis could discover a singer, say, Whitney Houston and try to make her a star by getting her music played in the places that everyone was listening, namely radio and MTV. Not everyone panned out, but there were clear levers to pull to make a star.

Because things are so fractured, that world doesn’t exist anymore. Artist development doesn’t exist in the same way. Artists are expected to have a fan base by the time they get a record deal in a way that Whitney Houston was not. Nobody can make you a star but yourself.

I feel like that’s the case in most industries now. Do you think book publishing functions in a similar way?

Totally. I’m pretty certain I would not be getting this book published if I didn’t have 9,000 subscribers to this newsletter and 100,000 followers on TikTok. Honestly, even with that audience, it still took me years to find a publisher!

Do you think that hinders art?

Art and commerce have always been wrapped together in ways that aren’t ideal. That’s the nature of business, though. You need to make compromises. Certain things always have a better chance of selling than others. There are tons of examples of artists having to make compromises at the expense of their work. But there are also examples of artists making compromises that ended up benefiting them, along with artists whose visions were so uncompromising that they never released anything.

All that said, it’s important to note that music and the music business are two different things. You can make music ignoring all economic pressures. Becoming a pop star involves some compromises, though.

Let’s talk a bit about touring. How do tours relate to successful singles and albums?

Tour revenue doesn’t factor in Billboard’s pop charts. There are some interesting dynamics in the touring world right now, though. Because so much fandom is built online, you see artists get record deals without ever having played a show. They’re thrown up on stage and have no idea what is going on. Some of these people go on to be dynamic live performers, but they’ve got to cut your teeth to get there. Historically, you almost couldn’t have a career without touring. Fan bases were built on the road.

All that said, I think live music continues to matter more than anything. I recently spoke to the head of legendary punk label, and he noted that even though TikTok and streaming matters so much that his biggest artists always build important connections playing live. There’s still not a great replacement for it. And I kind of hope there never is.

Independence Rocks: A Conversation with Hopeless Records' Louis Posen

If you enjoy this newsletter, consider ordering a copy of my debut book, Uncharted Territory: What Numbers Tell Us about the Biggest Hit Songs and Ourselves. It’s a data-driven history of popular music covering 1958 to 2025.

I recently read that concert tickets are selling faster than ever before. Is that true?

There was so much pent up demand for live entertainment during COVID that once lockdowns ended there was not only a boom in tours being announced but a boom in people willing to spend gobs of money to go to those tours. The one problem is that these high-end concerts—think Taylor Swift and Beyoncé—ended up squeezing out middle-class artists.

Most people have an implicit entertainment budget. If you are going to spend $800 on a Taylor Swift ticket that doesn’t leave much, if anything, to spend on other events. It can be tough out there if you’re not already a superstar.

Given all of the data that you’ve analyzed, what advice would you give up-and-coming artists?

You’ve sadly got to play the social media game. I know how annoying that is—imagine telling a young Kurt Cobian that he had to post on TikTok—but it is the case.

At the same time, online audiences can be very fickle. Except in certain circumstances, you’ve got to develop real connections with your fans outside of these platforms. I think the best way to build those connections in the year of our Lord 2025 is still to play live. The internet can bring you tons of eyeballs, but live performance is the bedrock of a career.

Are you a religious person?

Why do you ask?

You just said “the year of Lord 2025.”

Oh. I was just using that as an expression. I certainly have religious tendencies, but I’m not really a fire and brimstone type of guy.

You aren’t thinking about morality when listening to pop songs?

Almost never. I like to think that God has other concerns.

I think you’re right.

That’s not to say that art doesn’t have an impact on people. You can use art for good or bad purposes. The reason that I say that “God has other concerns” is because there have been decades of moral panics around the arts that often ended up being thinly veiled attacks on artists of certain races and genders. No matter what Tipper Gore says, rock music did not lead to a long-lasting boom of Satanists in the US. I talk a bit about this in Chapter 9 of my book.

Music is a very powerful force, though. I can’t deny that. I just think we get upset about things that don’t ultimately matter.

Would you say that music is one of the most primal art forms?

I think so. There’s a great book by critic and historian Ted Gioia called Music: A Subversive History that traces musical ideas back millennia. Every culture, no matter how primitive, has music in some capacity. Our need for it seems to be engrained. There’s a reason songs were used to get people fired up for war and songs are still played on loop in sports stadiums. Music has power.

I’m also not sure that there’s any other artistic medium that lends itself to repeat consumption more than music. Like I’m not going to watch the same movie four times in a single day.

Totally. Music is a bit different because it is portable, especially today. You can carry the entire history of recorded music in your pocket. Plus, even if you’re a Luddite, you just need to tap your toe and hum to bring music with you.

Would you like to be a musician or are you happy as a commentator?

I still love making music. I think it gives direct insight into certain things you can’t know otherwise. The creative process can be quite mystical. I need to be realistic, though.

I turned 30 about six months ago. I’ve seen the data. Popular music is a young person’s game. 30 is basically geriatric on the pop charts. Maybe I end up having a song that crosses over in some way at some point, but I don’t need that to happen. I still love making music whether one or one million people listen to it.

Want more from Chris Dalla Riva? Consider pre-ordering a copy of his book Uncharted Territory: What Numbers Tell Us about the Biggest Hit Songs and Ourselves.

Want more from Gordon Glasgow? Consider subscribing to his incredible newsletter 12 Questions.

What a great interview! Your journey to bestselling author is quite the story in itself. I can't wait to crack the spine of Uncharted Territory for myself!

Super informative interview Chris, I learned so much! At 30 you may consider yourself in the musical “geriatric” category (which I actually really doubt) but writing-wise you’re in peak tip-top shape. Fascinating read. Your astounding career and insightful perspectives have produced yet another total home run. Bravo!