Don't Believe the AI Lies

On music, democracy, and such

If you enjoy this newsletter, consider ordering a copy of my debut book, Uncharted Territory: What Numbers Tell Us about the Biggest Hit Songs and Ourselves. It’s a data-driven history of popular music covering 1958 to 2025. If you want your book signed, I am going to be at Little City Books in Hoboken, New Jersey, on Thursday, December 4 talking about the book with the incredible journalist Michael Tedder. (That’s tonight!) Reserve your spot if you’re interested. There will be books available there.

Now, let’s talk about a few lies that are being spread about artificial intelligence and music.

Don’t Believe the AI Lies

By Chris Dalla Riva

The madness started on Twitter. This time it was when start-up founder and internet personality Rosie Nguyen posted the following:

I grew up singing. I sang everywhere I went, I wrote songs in my diary, I told teachers that I wanted to be a singer & songwriter when I grew up.

But wanting to be a musician in 2006 required resources that a low-income family didn’t have. My parents couldn’t afford to get me any instruments. They couldn’t pay for music lessons. They couldn’t get me into studios. A dream I had became just a memory, until now.

I am beyond proud and honored to get to work at a company that is enabling music creation for everyone. For the 13 year old kid in their bedroom who dreams of being a musician, you can be one. For all of the professional artists, you can do more of what you love.

I really wish Suno existed 20 years ago when I was a kid in elementary school, showing strangers songs I wrote with no way to produce them. But I’m really, really happy that it exists today, for all of the other kids who might need it.

Suno—for those not in the know—is the buzzy music start-up raising gobs of money, getting sued by labels, and signing first-of-their-kind licensing deals with those same labels. Suno functions like a ChatGPT for music. You enter a prompt—maybe something like “off-kilter folk song about the solar system”—and it spits back a complete recording. It’s impressive, spooky, and somewhat off-putting.

In her post, Nguyen is ostensibly claiming that Suno is democratizing the creation of music. “I am beyond proud and honored,” she writes, “to get to work at a company that is enabling music creation for everyone.” Nguyen is far from the first person to make this claim. In fact, anytime you read about AI and music, it is bound to come up.

Forbes: “For me, one of the most exciting aspects of the recent wave of generative AI technology is the democratizing impact it has on creativity.”

The Hollywood Reporter: “As AI tools democratize music creation and reshape what productivity should look like for a singer or musician, things are starting to get weird, too.”

Associated Press: “It also cast a spotlight on AI song generators that are democratizing song making but threaten to disrupt the music industry.”

The problem with this argument is that it is basically untrue in every sense.

Music might be the most democratic art form. There has never been a human society discovered without music. And music exists across all economic strata of those societies. The five-year-old clapping along in church and the busker standing on the street corner are making music just like Jay-Z and Taylor Swift are making music. In 99% of cases, if you are making music on Suno, you could have made music without Suno.

The counterargument that I have come across is that humming a tune, for example, is not the same as making a full recording. There were still huge hurdles to making studio recordings.

I’m skeptical that anybody making that claim probably had tried to make a recording recently. In the last 20 years, the barriers to making recordings and distributing them throughout the world have come crashing down. In fact, even before generative AI tools rolled out, streaming services were already seeing more uploads in a week then were recorded across entire decades of the 20th century.

So, should we take this oft-repeated lie as evidence that any AI-powered music tool is the work of Satan? No. Having just spent years studying a century of music technology for my book, I know that all new technology faces backlash. And much criticism around generative AI feels similar to the criticisms that were levied at radio and synthesizers and drum machines and pitch correction and even recording itself. I would bet that at some point I will likely come to enjoy a song that involves AI in some capacity.

Still, I am skeptical of this technology. Let me explain.

Generative AI Cannot Work Without Other Recordings

When Suno was first announced to the world, it quickly became clear that the company had hoovered up every piece of recorded music on the internet to make their technology work. And they did that without permission or payment.

This is one of the fundamental differences between generative AI and earlier technology, like a drum machine. Yes, a drum machine can replace a human drummer. I don’t really have any issue with that, though. A drum machine can work without infringing on anyone’s intellectual property. Suno cannot.

As noted earlier, at the same time they are being sued, Suno is pursuing licensing deals with major music rightsholders. It’s looking like copyright holders will be compensated in some way in the near future. If Suno was some altruistic tool meant to empower artists that would have been baked in from the beginning.

But even if we get all of the licensing issues sorted out, my skepticism will still remain.

Generative AI Further Entrenches the Past

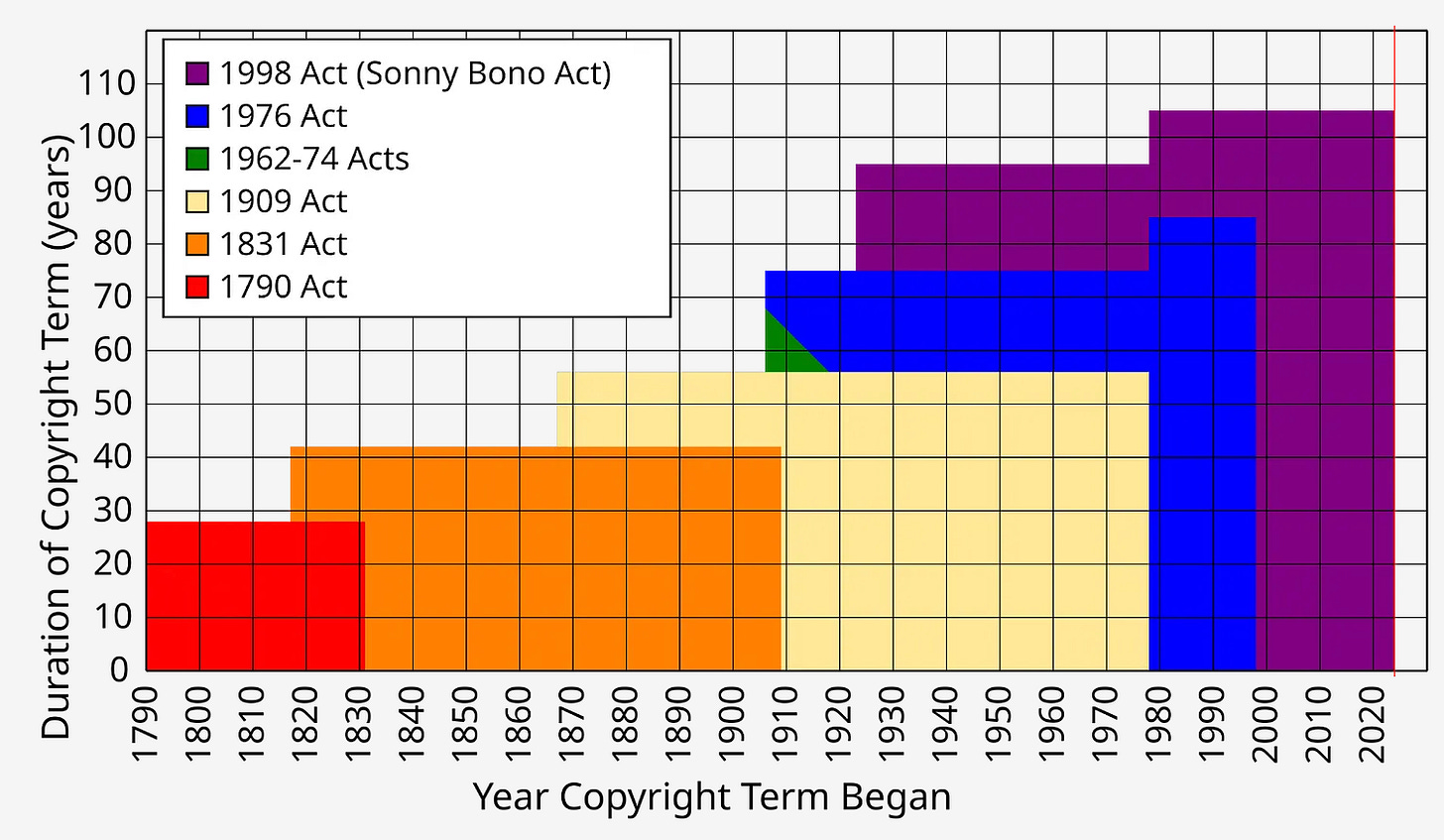

Last week, I wrote a piece for Matthew Yglesias’s Slow Boring about how exorbitant copyright terms can lead to cultural stagnation. The gist of the piece is that because copyright terms last a very long time—namely, the life of the author plus 70 years—we end up compensating the most successful artists long after they are dead at the expense of newer artists.

Again, let’s assume that Suno sorts out all of the licensing issues such that when you generate a song on their platform, they will (a) pay the rightsholders whose work was most fundamental to what was generated a percentage of subscription revenue and (b) grant a percentage of the songwriting royalties going forward when people listen to the new song. This would be a good thing!

But there are also some downsides. Most revenue would likely flow to the biggest hitmakers around. That’s fine in the abstract. But if all new work is automatically compensating the artists of the past, it makes it even more difficult for the next generation of artists to forge careers.

If we want culture to be robust, we need to make it easier for the next generation of artists to subsist. But, again, even if everyone agreed that AI ended a years-long cultural stagnation, my skepticism will still remain.

Generative AI Encourages Listening Alone

In preparation for this piece, I did a ton of reading in the Suno subreddit. There are people in the community who legitimately seem like they are trying to engage with a new technology to make interesting art. (I’ve actually spoken to some people who would fall into this group in the past.) Props to them.

But there are other subsets of users who fall into stranger categories. One group is furious that Suno signed a licensing deal with Warner Music Group:

Suno didn’t hit a $2.45 billion valuation and raise $375 million by accident. They got there on the backs of the community. Investors didn’t pour nearly $400 million into Suno because of the code... they invested because millions of users proved the product’s value by creating, sharing, and subscribing. We built the moat. Yet, when the legal pressure mounted, Suno treated the community not as a partner to defend, but as a liability to manage.

The irony of course is that this is a sentiment that many artists feel about the technology, but I digress.

But there is another group that concerns me the most. It is people who claim they make hundreds of songs on Suno in very niche styles that they intend to listen to by themselves and share with nobody else. These people have no commercial aspirations. They are making music for an audience of one.

While there isn’t an issue with making music for yourself, I need to re-stress that music is a fundamentally social art. From the birth of the Walkman to the rise of the iPod and the domination of algorithmic curation, the last 40 years have tried to convince us that music is a solo endeavor. It isn’t. Music is something that we share.

As surveys continue to indicate that people are lonelier than ever before, seeing people use this technology just to make hyper-personalized songs gives me great pause. As I’ve written in the past, I hope you never listen alone. Suno makes me think that one day we all might.

So, What Do We Do Now?

This technology likely isn’t going away. And there will almost certainly be fascinating art made with it in the future. In addition, it might have some useful applications that don’t involve generating finalized recordings, like demoing a song. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be concerned about it.

I will leave you with some principles that I have been using to guide my thinking during these weird times.

Technology is not inherently bad. It’s how we use it that determines if it is good or it is bad.

Artists deserve to be compensated for their work. If a technology is not built with this in mind, we should reject it.

If you suddenly see an avalanche of artists promoting a new technology on social media, they are likely part of a guerrilla marketing powered by whoever is behind it. Take those opinions with a grain of salt.

Music is an inherently democratic art form. Anyone who claims they have built something to “democratize music” is likely pulling a fast one on you.

Music is an inherently social art form. If musical technology discourages sharing songs and building connections, we should reject it.

A New One

"If You Know Me" by Hudson Freeman

2025 - Folk

Sometimes a single song is enough to lift a career to another plane. In Hudson Freeman’s case, it didn’t even take a song. It took a note. A few months back, the folksy Freeman posted a demo on TikTok of a new song that he’d been working on. The song opened with a deep, hypnotic bend on the G-string. And people were hooked.

As the weeks went by, Zach Bryan expressed his love for the song. Soon after, John Mayer was trying to figure the riff out. And after all of that, Freeman finally graced us with the studio version. It was worth the wait.

An Old One

"Soul Man" by Sam & Dave

1967 - Soul

I had to run to Target late last night. When I hopped in the car, a newscaster informed me that Steve Cropper had died. I was heartbroken. If you listed the ten greatest soul records of all-time, it’s possible that Cropper guitar played on half of them. Like his 1960s contemporary George Harrison, Cropper’s superpower was never overplaying. You can see that well on Sam & Dave’s “Soul Man.”

While Cropper’s rhythm work is the backbone of the verses, he pulls back on the chorus and snakes some riffs between the soul duo’s vocals. Sam Moore is clearly impressed. After Cropper bends a note on the second chorus, Moore shouts, “Play it, Steve!” Wherever Mr. Cropper is now, I hope he keeps getting to play it.

If you enjoyed this piece, consider ordering my book Uncharted Territory: What Numbers Tell Us about the Biggest Hit Songs and Ourselves. The book chronicles how I listened to every number one hit in history and used what I learned during the journey to write a data-driven history of popular music from 1958 through today.

Should you want to sign a copy, come to Little City Books in Hoboken, New Jersey, on Thursday, December 4. Reserve your spot today!

I struggle with this argument. Most people actually *can’t* make music, at least of any quality. A child clapping is “music”, sure, but not art. The percentage of humans who can make music of quality is vanishingly small. I’m reasonably musical, play an instrument, and I’ve "made" a song with Suno, but that was months ago and I’ve never done it again, because I don’t have the desire - there’s no music in me trying to get out. But I could not / would not have made that artifact without Suno.

Conversely, I’ve written an entire book. An enormous effort. I could have used AI to do some of it, but what would have been the point?

If you use AI to make something, in what sense have you really “made” it? More like you “requested” it. Art happens when the artist has some inner truth that wants to come out. It usually requires effort and sacrifice and craft, none of which are much required to use AI. I suspect most people's use of Suno will be one-and-done, unless they need an artifact for their job (a jingle, let's say) - or a logo created with AI image gen - these things are not art, they are work artifacts, largely.

AI may well create entertainment, but I don’t think it can create art, because art is a relationship, not an artifact.

Such a good post, Chris! Agree with all of this. The desire to just make things appear without the work or effort is so antithetical to the artmaking process.