How Cover Art Predicted the Future

Today, I'm excited to share another excerpt from my debut book, Uncharted Territory

If you read this newsletter regularly, you’ll know that I have a book coming out this fall. It’s a data-driven history of popular music called Uncharted Territory: What Numbers Tell Us about the Biggest Hit Songs and Ourselves. If you’re a fan of the newsletter, you’re sure to like the book.

Each month until publication, I am sharing excerpts from the book. So far, we’ve shared pieces about the 1970s, 2000s, and 2010s. This month, I want to turn to the 1980s to talk about how cover art explains much of the modern music industry. The only thing you need to know is that if a song is followed by a date (e.g., “Crazy for You” by Madonna (May 11, 1985)), then that song was a number one hit and that was the date it topped the charts.

Dig, If You Will, the Picture

By Chris Dalla Riva

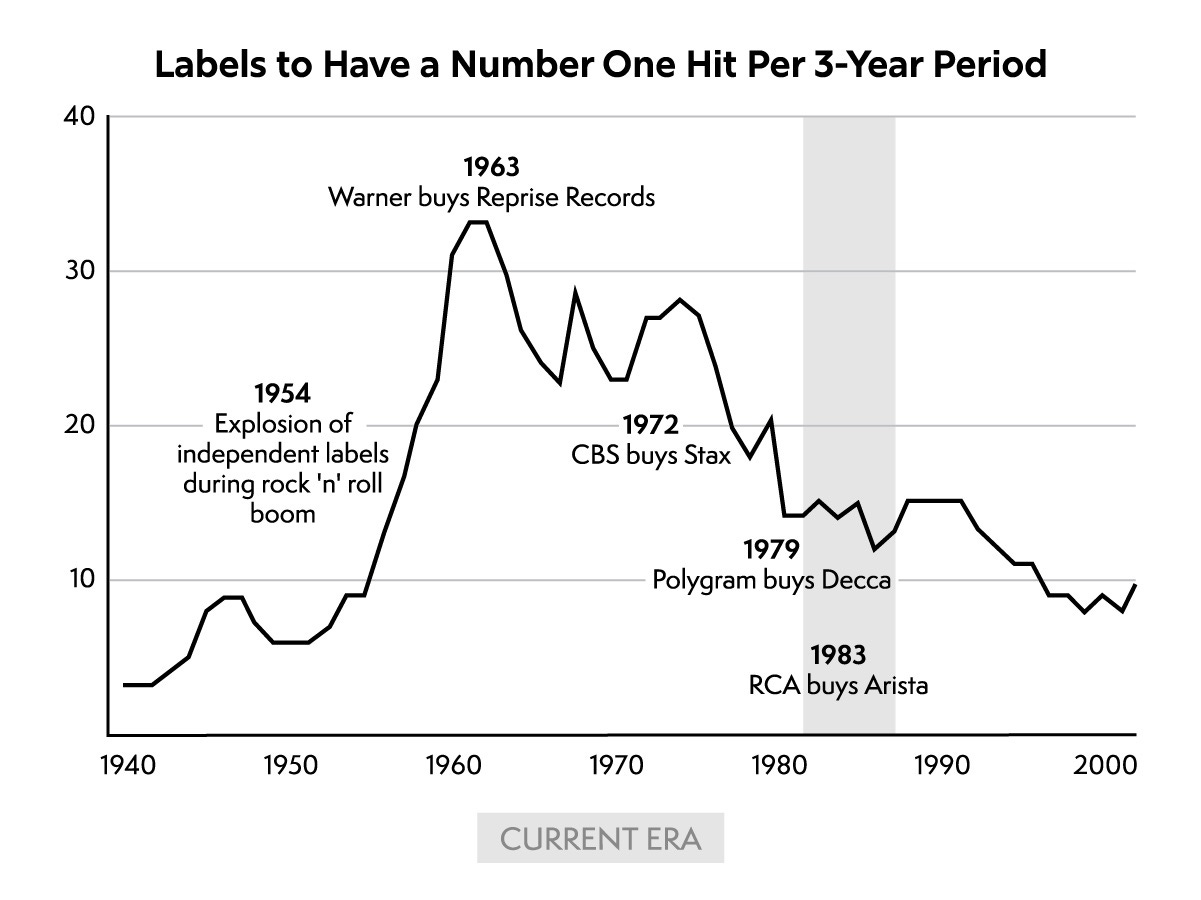

Business historian Alfred D. Chandler, Jr. described industry maturation in the United States as “ten years of competition and 90 years of oligopoly.” While I appreciate that aphorism, the evolution of the music industry has been more like 70 years of oligopoly, 20 years of competition, and then a lot more oligopoly. We can see this general pattern by looking at the unique number of labels to send a song to number one between 1940 and the end of this era.

In the first half of the twentieth century, the music industry was dominated by three labels: RCA, Columbia, and Decca. Some of their power came from the fact that they had created technology that was required to record and manufacture music. Then around 1950, there was an explosion of independent labels. As noted in Chapter 3, this explosion was driven by the economic boom after the Second World War, along with the emergence of the teenage demographic. You can see this in Figure 7.4. Between 1943 to 1945, every number one was released by one of four labels. From 1961 to 1963, that number had jumped to 33. By the end of that decade, the reconsolidation began, though.

According to economic historian Gerben Bakker, there were three medium-to-large-sized mergers and acquisitions in the music industry in the 1950s. Between 1967 and 1977, there were 13. Between 1978 and 1988, there were 15. In the next decade, there were 34. By 2000, nearly every notable independent label of the twentieth century, from Atlantic to Def Jam and Motown to Virgin, had been gobbled up by international conglomerates like Sony, Universal, and Warner.

Before we talk about one of the most under-discussed effects of this conglomeration, we should answer a question we’ve been circling around in a couple parts of this book: What is a record label? In broad strokes, a record label is a company that does the following:

Identifies musical talent

Pays for that talent to record songs

Manufactures and distributes those recordings in a variety of formats

Promotes those recordings to listeners

Though we’ll talk about this a bit more in Chapter 10, when an artist signs a recording contract with a label, the agreement is usually that the label fronts the artist money to make a specified number of albums. Once an album is manufactured, distributed, and promoted by the label, the artist won’t make anything until the label recoups what they spent out of the artist’s royalties.

While that deal structure and the function of labels were the same for a long time, the music industry looked very different in 1985 compared to 1965. There were now fewer labels operating outside the purview of the corporatized and financialized media conglomerates chasing ever-higher profit margins. And the independence of small labels would continue to dwindle as these larger companies monopolized distribution.

Distribution was a notoriously hard problem. You could make a song as good as Cyndi Lauper’s “Time After Time” (June 9, 1984), but nobody was going to be able to buy it if you couldn’t get it to record shops across the globe. Though some big labels in the first half of the twentieth century ran distribution networks, there were many independent companies that offered those services. This gave small labels a bunch of options when they needed a distributor. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, bigger labels devoted more resources to distribution. One way to make sure your distribution plants were operating efficiently was to assure they weren’t waiting around for more music. Purchasing smaller labels was a great way to have an endless flow of records coming through the pipeline.

As big labels started to distribute more music—even those records they didn’t technically own—it became increasingly difficult for small labels to compete. You might expect that this conglomeration would lead to musical homogeneity. That seemed to be the case with the major labels in the 1940s. They weren’t nimble enough to keep up with the changing desires of their listeners. But the conglomerates of the 1980s were very different.

Sure, Madonna’s “Crazy for You” (May 11, 1985) and Phil Collins’ “Sussudio” (July 6, 1985) were both released by the giant Warner Music conglomerate. But “Crazy for You” was promoted on the Warner subsidiary Geffen, while “Sussudio” came out on Atlantic, another Warner property. Yes, the respective success of those songs was benefiting the same corporate balance sheet, but these subsidiaries were in such fierce competition that many of the label heads hated each other. In short, though oligopoly reigned in the 1940s and 1980s, the 1980s’ version of that oligopoly was much less centralized than that of the 1940s.

While this corporate concentration has generated enough repercussions to fill up a book by itself, including many related to the proliferation of the music video, it also led to a less-discussed change: the still image revolution.

The Still Image Revolution

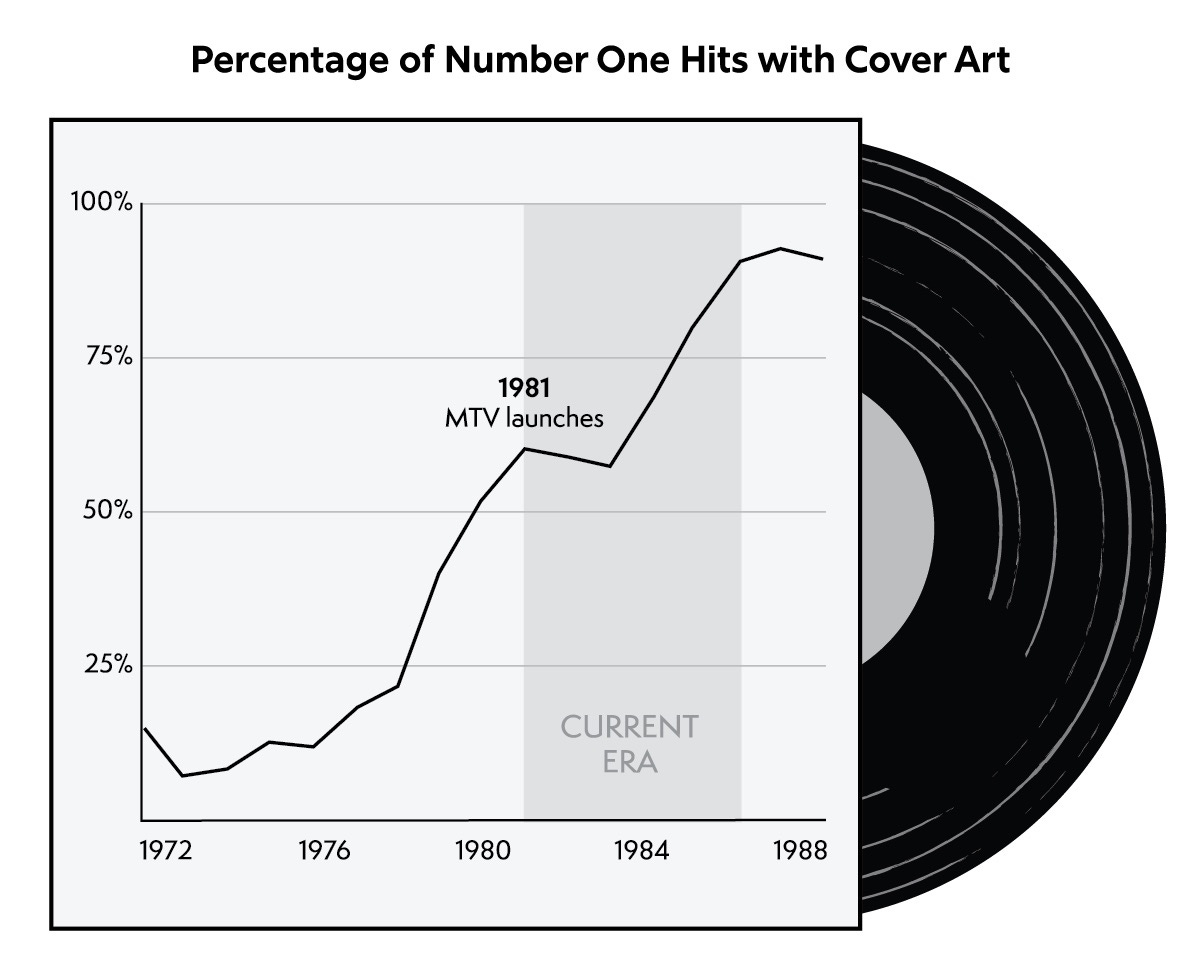

Before Columbia Records hired Alex Steinweiss as its art director in 1938, albums did not have cover art. They were sold in generic packaging that labels could mass produce. Steinweiss realized that if an album were packaged with engaging art, it sold more copies. Other labels followed suit, and most albums since have been released with a front-facing image. The singles market was slower to adopt this visual counterpart, though.

As you can see in Figure 7.5, there was a growing interest in single cover art before this era, but its use became commonplace as the importance of MTV and image grew. I spoke to both Joel Whitburn and Fred Bronson, two leading authorities on the Billboard charts, and they concurred that this finding goes beyond the number ones. Single cover art wasn’t prevalent until the 1980s.

While the relationship between single cover art and videos feels obvious, its connection to label conglomeration is a bit more subtle. To understand that connection, I first need to note how most singles before this era, like albums pre-1938, were sold in generic packaging.

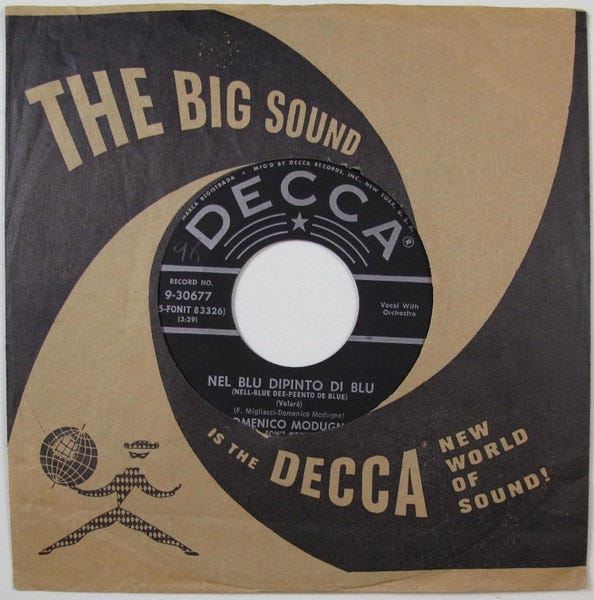

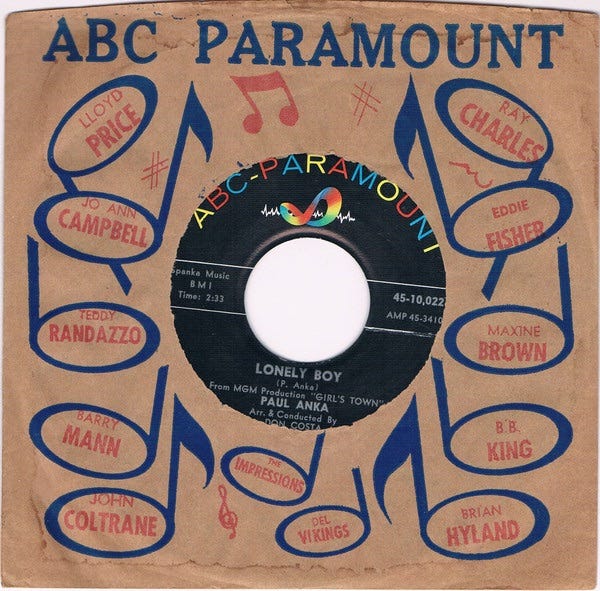

The two sleeves pictured in Figure 7.6 are respectively from Decca and ABC-Paramount releases in 1958 and 1959. The Decca packaging is plain, mostly highlighting the name of the label, while the ABC-Paramount packaging stresses both the name of the label and other notable artists on their roster.

Most singles up to 1980 were packaged like this. If anything was promoted on the sleeve, it was for the label rather than the artist. This was for two reasons. First, it was cheaper to produce generic sleeves for all of a label’s singles, which was important given that the financial return was smaller for singles than for albums. Second, independent labels had a stronger incentive to promote affinity for themselves rather than for a specific artist.

Motown proves a good example of this. Because there was sonic cohesion among Motown records, if you bought a Mary Wells song and saw the Four Tops advertised on the sleeve, you might go out and buy their record. This was even true of Motown through this era. If you liked Lionel Richie’s ballad “Hello” (May 12, 1984), there was a good chance you’d also like Stevie Wonder’s ballad “I Just Called to Say I Love You” (October 13, 1984). Nearly every other label started out like this. Atlantic focused on rhythm and blues. Casablanca focused on disco. Def Jam focused on hip-hop.

But as these labels were subsumed into larger companies, their distinctness was erased. Nobody, for example, was buying Billy Joel’s “Tell Her About It” (September 24, 1983) because it was released on Columbia Records. In 2000, New York Times critic Jon Pareles made this exact point: “While a small label . . . can build insider cachet . . . The bigger the company, the less it means to people who care about a certain performer. The majors are so large that, paradoxically, they seem invisible.” Because of this effect, it no longer made sense to advertise a label on a single sleeve. It made sense to advertise the artist, especially as music videos and images were ascendent.

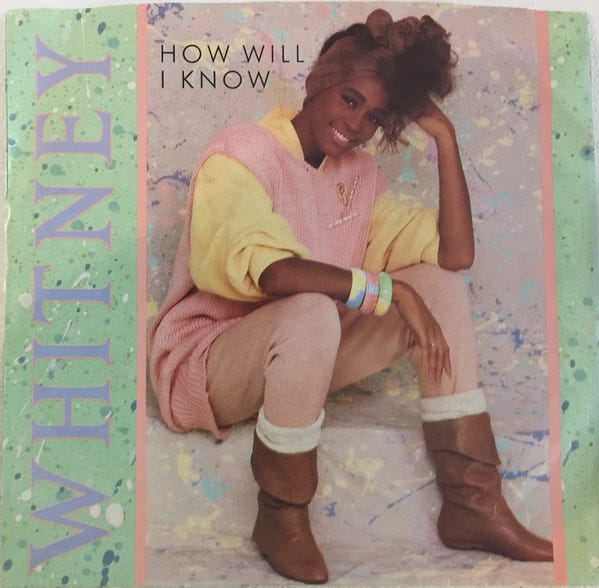

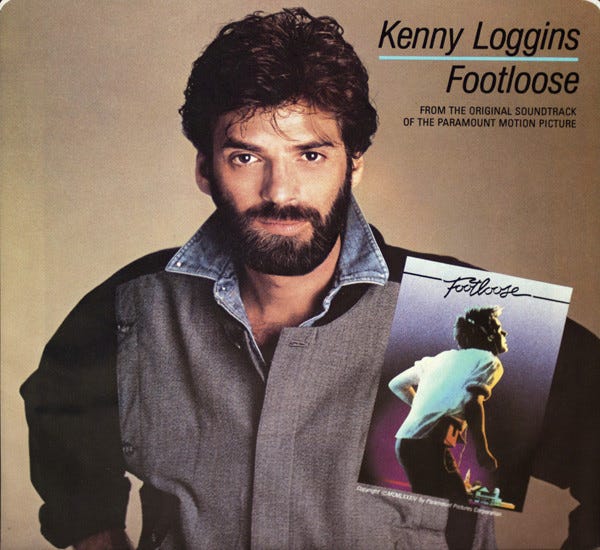

While certain pieces of album artwork have become iconic—the opening monologue of Prince’s “Let’s Go Crazy” (September 29, 1984) almost involuntarily conjuring the image of the singer sitting on the motorcycle found on the cover of Purple Rain—single art is often more generic. As with Kenny Loggins’ sprightly “Footloose” (March 31, 1984) and Whitney Houston’s aching “How Will I Know” (February 15, 1986), it usually features a picture of the artist that was likely produced cheaply.

And if that wasn’t cheap enough, sometimes the label would repurpose the artwork they were using for the album the song belonged to. For example, Phil Collins’ droning “One More Night” (March 30, 1985) and The Police’s sultry, stalker-anthem “Every Breath You Take” (July 9, 1983) are modified artwork from the former’s No Jacket Required and the latter’s Synchronicity.

While music videos can often generate polarizing opinions—in fact, Billy Squier has claimed that his awkward dancing in the video for his song “Rock Me Tonite” abruptly ended his career—single cover artwork seldom receives a comment, especially since it was relegated to a small thumbnail on the computer in the 2000s. That said, it’s a good example of how seemingly innocuous things in the music business can signify deeper changes.

This was an excerpt from Chris Dalla Riva’s forthcoming book, Uncharted Territory: What Numbers Tell Us about the Biggest Hit Songs and Ourselves. If you enjoyed it, you can pre-order a copy of the book today. And if you think you have a way for Chris to promote the book, please reach out via this form.

I saw Billy Squier in concert on that tour. The opening band was Ratt.

Interesting piece as always, Chris - really looking forward the book!

I'm sure that MTV spurred more labels into releasing singles with picture sleeves in the '80s, but weren't there also quite a few in the previous two decades? I own an almost-complete run of The Beatles original VeeJay and Capitol/Apple singles, all with [mostly] color picture sleeves completely different from the album art. I can also think of many U.S. Stones, Yardbirds,

Dylan, CCR and other 45s from the '60s with cool picture sleeves.

And in Europe and other 'Westernized' countries around the world there were a ton of 'em in the '70s - Led Zep, The Who, Dylan and almost any other well-known act you can mention had picture sleeve singles released outside the U.S. in the '70s, some of them graphically stunning.

And yes, when punk came in some very cool pic sleeves resulted, mostly from the UK.

I'm not contesting your information or conclusions, just calling attention to some of my favorite collectibles!

https://open.substack.com/pub/hughjones/p/the-record-store-years-25-the-late?r=6o97f&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false