Revisiting the Death of the Key Change

I look back on the piece that made me "famous" to see if anything has changed

It’s been an exciting few weeks at Can’t Get Much Higher. Last week, the long-running newsletter Kottke linked to my story about the greatest two-hit wonders of all-time. A week before that, the economist Tyler Cowen shared my piece about the pop music kill rate. His share sent the post to the top of Hacker News. Then right around the same time, some folks on LinkedIn started debating my piece on old music eating new music.

In other words, we’ve got a lot of new subscribers. If you are one of those new people, thanks for stopping by. (I hope I don’t let you down.) If you’re an old friend, welcome back.

Revisiting the Death of the Key Change

By Chris Dalla Riva

If everyone gets their 15-minutes of fame, I had mine a few years ago. At the time, nobody wanted to publish anything I’d written. In fact, I don’t think I could even pay someone to publish anything I’d written. Then Ernie Smith came along.

Smith is the proprietor of the long-running website and newsletter Tedium. And he somehow decided to let a nobody like me write about how there were fewer key changes in pop songs. While I thought this topic was kind of esoteric — who cares about key changes? — it quickly caught fire online.

As I scrolled through Twitter in the following days, I would see professional musicians whom I admired arguing about what the takeaway from the article was. I had national publications reach out to me for comment. This led to an appearance on NPR and a column in The Economist. Everyone wanted a piece of Chris Dalla Riva for a few weeks.

Of course, the frenzy died down. There’s only so much you can say about one chart. But I was able to parlay that popularity into growing this newsletter. And that growth eventually led to a book deal. Nevertheless, I thought it might be nice to revisit that piece since it’s been a few years. Maybe the trend had changed.

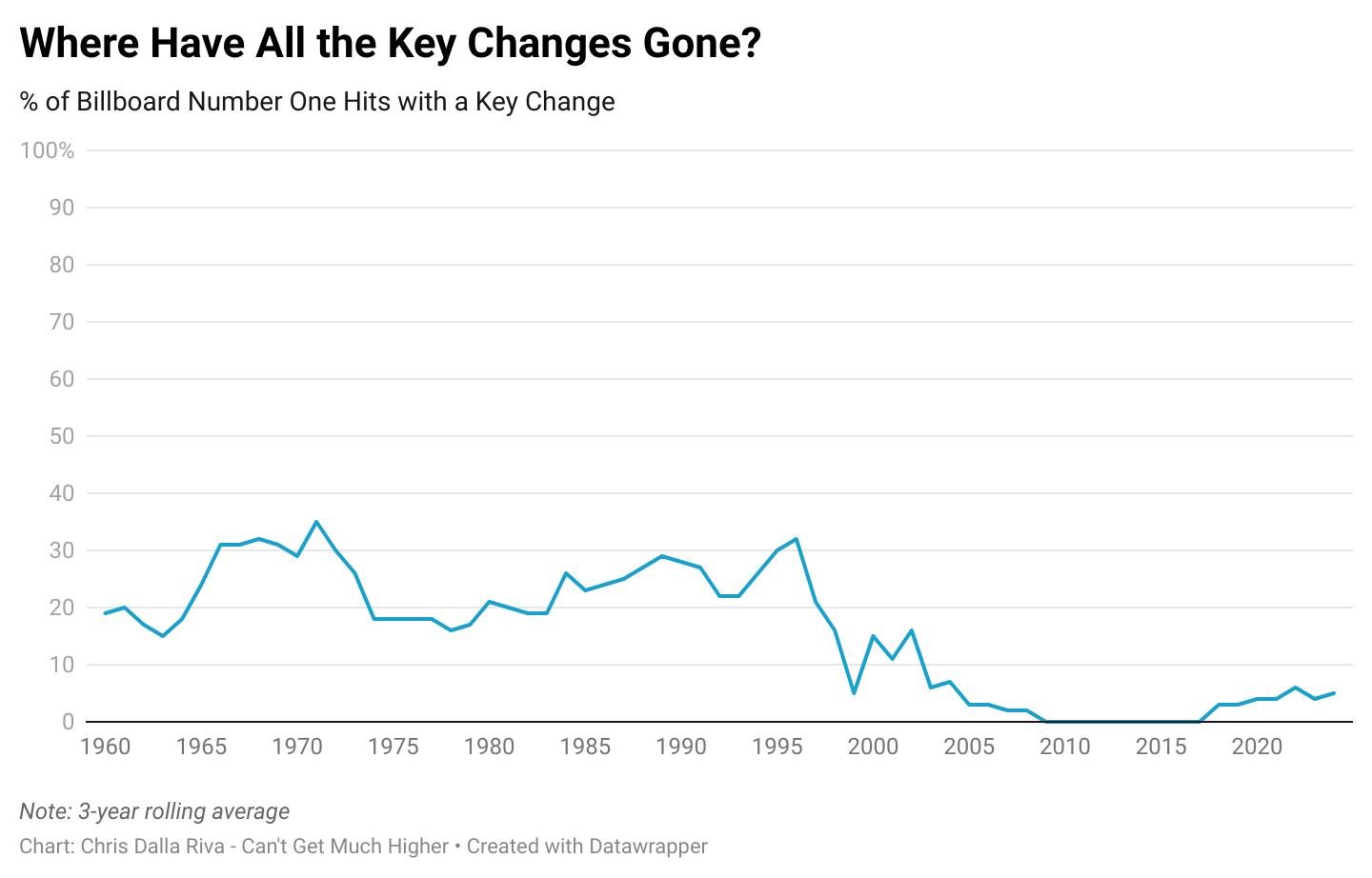

Above you can see a chart that is very close to what I published in the original article. From 1960 to 1995, between 20% and 35% of Billboard Hot 100 number one hits in any given year contained a key change. Around the turn of the millennium that rate started to dip until it hit 0% by the end of the 2000s.

I think the reason this chart went viral was because people could see whatever they wanted to in it. You had people saying that it represented the death of sophistication in popular music, which in turn signified a more general dumbing down of culture. You had others claiming that it was nothing to worry about. We build sophistication into our popular songs in other ways these days.

These polarized reactions fascinated me because the article wasn’t a condemnation or celebration of the trend. It was an attempt to figure out why this happened. While I defer to the original article for more context, I think the trend was largely driven by the rise of hip-hop — a genre that focused more on lyricism and rhythm than harmony — and the proliferation of digital production. In the years since, has this trend remained the same, though?

From 2005 to 2015, there were two number one hits that contained a key change, Clay Aiken’s “This is the Night” and Taylor Hicks’ “Do I Make You Proud.” Both by American Idol contestants, these were hardly representative of popular music as a whole. Nevertheless, from 2015 to 2025, they key change began to resurrect, five number ones utilizing the musical device: Travis Scott’s “SICKO MODE,” BTS’s “Dynamite,” Silk Sonic’s “Leave the Door Open,” Drake’s “Jimmy Cooks,” and Sabrina Carpenter’s “Please Please Please.” How should we interpret this?

First, does a key change imply musical complexity. Not always. If I wrote a song that changed the key erratically every 7 bars, you’d probably think I was insane. Furthermore, from 1960 to 1990, 60% of songs with key changes use what might be the simplest key change, sometimes dubbed the “gear shift key change.”

Key changes of this type push the key up a half step or a whole step for the last chorus (i.e., A major → G major). Good examples of this can be heard in Frank Sinatra’s “Strangers in the Night,” Michael Jackson’s “Man in the Mirror,” and Whitney Houston’s “I Wanna Dance with Somebody (Who Loves Me).” Sure, this injects energy, but I wouldn’t celebrate this technique as an example of musical sophistication.

Nevertheless, it is interesting that among the five number one hits to use a key change in the last decade, only BTS’s “Dynamite” uses this overused device, the song shifting from E major to F# major towards the end. The other key changes are more intriguing. “Please Please Please,” for example, shifts from A major to C major for the second verse before returning to A for the rest of the song.

Does this mean that we should expect to see more key changes in the coming years? If you trust that the cause of their decline was the ubiquity of hip-hop and digital recording, then no. Hip-hop still remains a powerful force, and digital production isn’t going away. We’ll probably need some new style to arise if we want to bring the key change back. And if it comes back, I hope it’s at least used a bit more deftly than it was during the last quarter of the 20th century.

What About the Time Signature Change?

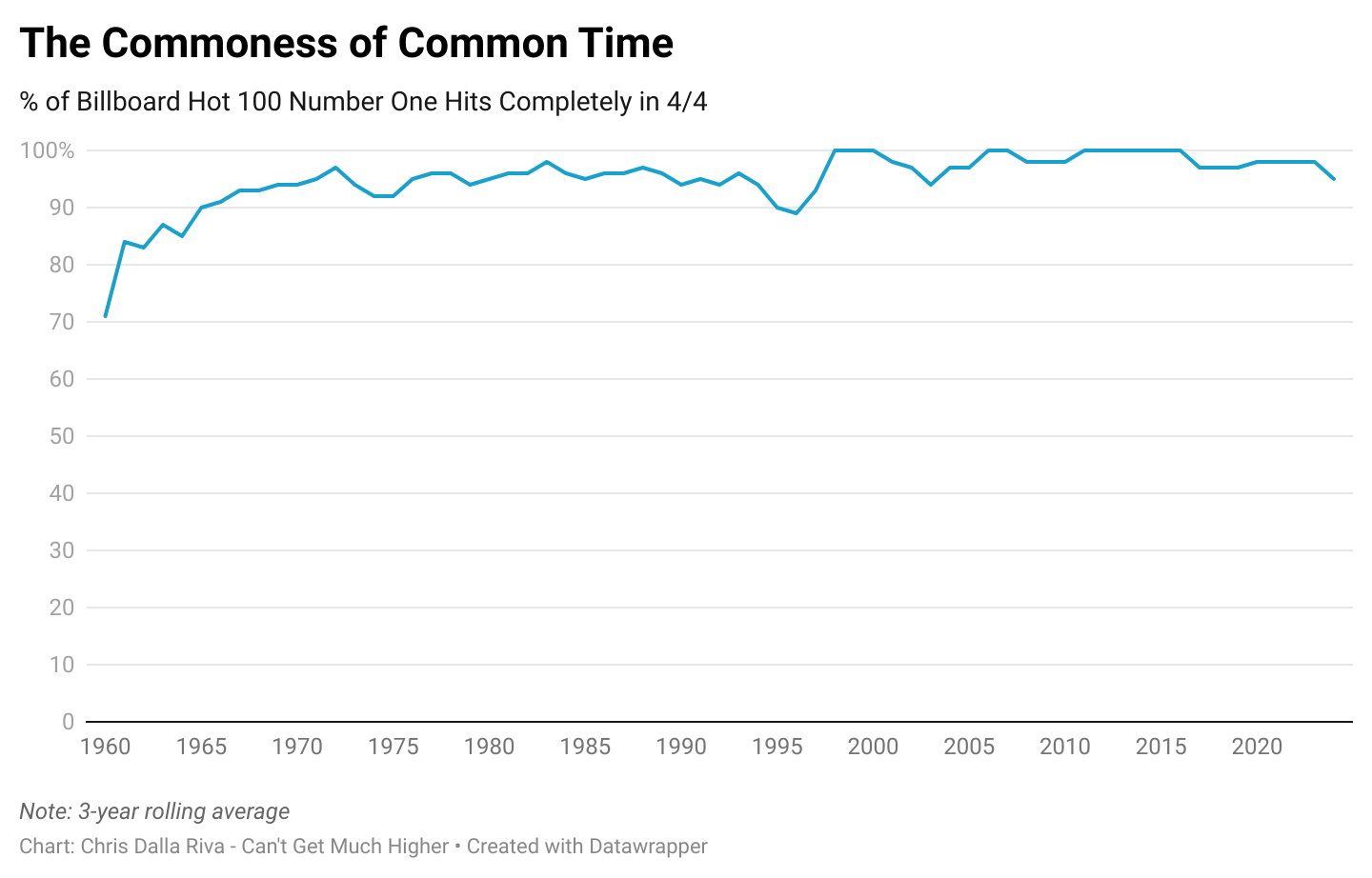

If harmonic changes (i.e., key changes) are a thing of the past, what about time signature changes? Though popular music has been obsessed with 4/4 for a long time — I mean it is also referred to as “common time” — it’s ubiquity since the 1970s would make you think that no other time signatures exist. They do. For decades, waltz-related time signatures were common on the pop charts (i.e., 3/4, 6/8). With the slight resurgence of key changes in the last decade, have we also seen more songs outside of the 4/4 universe?

No. Popular music, especially at the top of the charts, is still afflicted with a 4/4 addiction. Nevertheless, in the last decade, we have gotten some waltzing chart-toppers for the first time in a long-time, like Ed Sheeran’s “Perfect,” Ariana Grade and Justin Bieber’s “Stuck With U,” Teddy Swims’ “Lose Control,” and Bruno Mars and Lady Gaga’s “Die with a Smile.”

This list doesn’t include what, in my opinion, is the most unexpected rhythmic number one in recent memory: Zach Bryan’s “I Remember Everything.” While the chorus of this ode to lost love is in 4/4, the verses are in 7/4, a true pop oddity. I’m sure this wasn’t an active decision on Bryan’s part. The vocal phrases just ended up being an odd length. But they are a breath of fresh air. Don’t be afraid to leave common time behind every now-and-again.

A New One

"Run It Up" by Hanumankind

2025 - Hip-Hop

Born in India but raised around the globe, Hanumankind gained recognition in 2024 with the release of “Big Dawgs,” a song most notable for its death-defying music vibe. The rapper’s latest release didn’t attract me for its visuals, though. It was its rhythm. Yes, “Run It Up” is in 4/4 like most popular music in 2025, but Hanumankind plays around with the subdivisions of that rhythm in ways that are enthralling.

An Old One

"Never Gonna Let You Go" by Sérgio Mendes

1983 - Adult Contemporary

In a 2021 video, YouTuber Rick Beato referred to Sérgio Mendes’s hit “Never Gonna Let You Go” as “the most complex pop song of all time.” Written by famed songwriting duo Cynthia Weil and composer Barry Mann, the song is hopelessly complicated for a pop song, the key changing constantly. Nevertheless, the most miraculous thing about the song is that there is a memorable melody over that progression.

Shout out to the paid subscribers who allow this newsletter to exist. Along with getting access to our entire archive, subscribers unlock biweekly interviews with people driving the music industry, monthly round-ups of the most important stories in music, and priority when submitting questions for our mailbag. Consider becoming a paid subscriber today!

Recent Paid Subscriber Interviews: Pitchfork’s Editor-in-Chief • Classical Pianist • Spotify’s Former Data Guru • Music Supervisor • John Legend Collaborator • Wedding DJ • What It’s Like to Go Viral • Adele Collaborator

Recent Newsletters: Supermarket Music • The Lostwave Story • Blockbuster Nostalgia • Weird Band Names • Recorded Music is a Hoax • A Frank Sinatra Mystery • The Pop Music Kill Rate

Want to hear the music that I make? Check out my latest single “Overloving” wherever you stream music.

Hi Chris,

For me, the following is the greatest recording with not only key changes beyond Bobby Darin’s "Mack The Knife", but a "tempo accelerando" that even Rossini would admire:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uRWyxzmNdJc

Andrew - Homzy.ca

Quite a few questions here; first off, eyeballing chart one, "Where Have All the Key Changes Gone?", then the average (of a three year rolling average) number of number ones, in the discrete chart ranking, with key changes from 1960 to about 1997 is roughly 25% or thereabouts.

Which means that 75% or so don't have them. So, those songs are outnumbered 3-1, a small chunk of the total population. Is this a problem of small numbers? The population is only the number ones, we don't know about top tens, twenties, or the other 99 songs on the chart in each week.

However, there seem (eyeballing) to be three distinct periods, each roughly ten years in length, '65 to '75, average about 30%, pretty stable, '75 to '85, 20% - again stable, then '85 to '95, 25% - but more volatile than the other two.

What's going on there? If the rapid adoption of DAWs, sequencers, is a major driver post-'95, then are there similar changes in production techniques or technology in the previous periods? Seems likely, but do these periods match (lagging?) US recessions? That'd give consumer expectations shifting behaviour.

Something else? There's something akin to a dead cat bounce around 2000/02, then the downward trend to flatlining until when? 2016? Funny old year that.

I think something else has been going on - that song complexity is correlated to buyer expectations of the political and economic environment. Chart two already shows something of a recovery, and I'll bet that continues and accelerates. I'd peg the level back at 20% by 2028. I have no idea whether a new genre would emerge, but I would predict that lyrical content, producer messaging, will shift. A specific example would be a British band, UB40.

I expect that the usage of common time will change as well. I'd have to guess as to whether that might reflect a new genre or not. Not a musician, so I don't have a scooby.

Additionally; over the whole period, has consumer behaviour become more legible to producers, such that they are more capable of optimizing output to the observed behaviour? Streaming would present far more feedback to producers - if my predictions are correct, the shift could be very dramatic indeed - well within the three year window on your rolling average.