You Don't Have to Read Music to Make Music

We need to stop perpetuating the myth that being able to write and read sheet music somehow makes you more of a musician.

Two years ago, a documentary came out about Paul McCartney that saw superproducer Rick Rubin and Sir Paul talking about music. The documentary was fascinating, but when McCartney said the following, I couldn’t help but roll my eyes:

You know I meet a lot of young groups, and I say I can’t read music or write it. And they go, “What?”

I sometimes hear popular artists express this sentiment as if it’s something that should shock us. It shouldn’t. In fact, it’s a myth that you need to know how to read music to make music.

A Brief History of Transmitting Songs

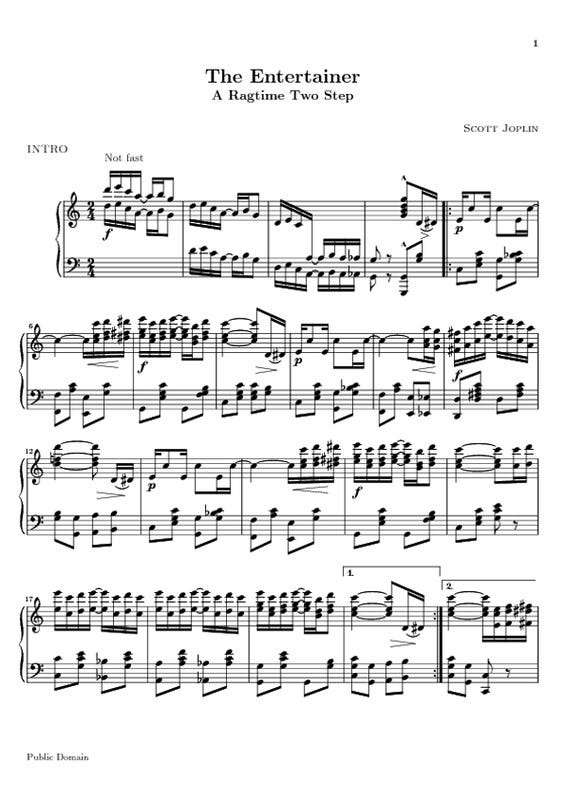

When I was first learning how to read music, my guitar teacher pointed out that music is not what’s written on the page. It’s something you play and something you hear. Written music is not music. It’s just a way to preserve and transmit it.

There are many ways to transmit a composition that don’t involve sheet music. The two that I most frequently interact with are chord charts and tablature. There are drawbacks to each of these methods – for example, tablature doesn’t tell you how long to hold each note – but they still have value.

In a certain sense, we have the ultimate way to transmit a composition: recording. Every other method is going to miss out on some nuance. This is the way that McCartney and his compatriots learned how to play. They listened to recordings and figured out how to imitate them. This is just as valid an approach to learning as reading sheet music.

This isn’t to say that sheet music isn’t valuable. Before the advent of recording, it was a much more reliable way to preserve a composition than, say, the oral tradition. And even today if you are getting an orchestra of 40 people together, you wouldn’t want everybody learning by ear. You would want a standard text that they could all work from. But knowing how to read sheet music does not necessarily make you a better musician.

Furthermore, the ability to read sheet music does not mean you know how music works. While McCartney was not formally trained, he certainly has deep knowledge of how melodies and harmonies function. He may not use the same language to describe those things as a conservatory student, but he has a deep understanding of them.

I’m so passionate about eradicating this myth because I think it discourages people from creating music. By all means, you can learn to read sheet music. As I’ve said, sheet music has value. But don’t think that noodling on the piano in order to figure out how to play the melody of a Billie Eilish song is any less of a musical act than the New York Philharmonic performing Beethoven’s 5th Symphony written out on a piece of paper.

A New One

"Dummy" by Portugal. The Man

2023 – Indie Rock

When I was tenth grade, my friends dragged me to see the Alaskan rockers Portugal. The Man at a tiny venue in New Jersey. The band sounded great, but I can’t express how shocked I was when seven years later they scored a top five hit with their song “Feel It Still.” Most bands don’t put out their first smash a decade into their career.

With a chorus that will rummage in your head for days, “Dummy” sees the band continuing to lean into the sound that made them popular. What’s cool is that in order to crossover into the mainstream, they didn’t have to turn their backs on their original fans. They just had to give that indie rock sound I heard all of those years ago a bit more shine.

An Old One

"I Love You Always Forever" by Donna Lewis

1996 – New Wave Pop

There are popular songs, and then there is the “Macarena.” The insatiable dance number topped the Billboard Hot 100 for 14 weeks in 1996. In fact, it was so ubiquitous that politicians did the dance at the 1996 Democratic National Convention. Whether you like the “Macarena” or not, the sad thing about something going to number one for so many weeks is that many songs get stuck behind it. One of those songs was Donna Lewis’s “I Love You Always Forever.”

“I Love You Always Forever” moves with a quiet verve and demonstrates how a single word can dramatically change the power of a lyric. Lewis didn’t need to include both “always” and “forever” in the title. “I love you always” and “I love you forever” ultimately mean the same thing. But had she left out either word, it would have come across as a run-of-the-mill love song. By combining both “always” and “forever,” the song goes from maudlin to the warm feeling of falling in love for the first time.

Want to hear the music that I make? Check out my latest EP.

All good stuff, Chris.

As a musician who struggled with reading sheet music when I first started playing, I absolutely love this article and actually felt validated after reading it. I play mostly by ear, using tabs if I'm stumped or in a hurry when trying to learn a song. This doesn't make me less of a musician than someone who does read sheet music. But I do have great respect for those who do!