Are Pop Songs Getting Sadder?

The final excerpt from my debut book, Uncharted Territory

If you read this newsletter regularly, you’ll know that I have a book coming out this fall. It’s a data-driven history of popular music called Uncharted Territory: What Numbers Tell Us about the Biggest Hit Songs and Ourselves. If you’re a fan of the newsletter, you’re sure to like the book.

Each month until publication, I am sharing excerpts from the book. So far, we’ve shared pieces about the 1970s, 1980s, 2000s, and 2010s. In the final excerpt before publication, I want to talk about contemporary music, specifically delving into the idea that pop songs got sadder in the last decade. The only thing you need to know is that if a song is followed by a date (e.g., “Happy” by Pharrell Williams (March 8, 2014)), then that song was a number one hit and that was the date it topped the charts.

It’s So Sad to Think About the Good Times

By Chris Dalla Riva

In Chapter Two, when we spoke about the joyfulness of music in the early 1960s, I recalled a conversation that I had with George O’Har, one of my college professors. Here’s what he said: “I find myself listening to mostly Latin music these days because American pop music is just so depressing. Pop music is supposed to bring people together and make you feel good.”

My former professor made that statement during the height of the era covered in this chapter. And I remember nodding along in agreement. Many of the Latin-infused songs that topped the charts in this era—like Luis Fonsi, Daddy Yankee, and Justin Bieber’s “Despacito” (May 27, 2017) and Cardi B, Bad Bunny, and J Balvin’s “I Like It” (July 7, 2018)—were dripping with joy.

At the same time, if you tossed every other chart-topper into a bag and reached in to grab one, I felt certain you’d come out with a song that was wholly depressing. But as with everything in this book, we trust our gut but make sure it isn’t deceiving us. And in this case, there doesn’t seem to be any deception. There are a few caveats, though.

During the 2010s, there was a slew of research conducted on sentiment expressed in popular songs. Nearly all of it showed a growing degree of sadness or anger.

A May 2018 study by six mathematicians out of the University of California, Irvine found that across 500,000 songs released in the United Kingdom between 1985 and 2015, there was a “clear downward trend in ‘happiness’ and ‘brightness,’ as well as a slight upward trend in ‘sadness.’”

Seven months later, computer scientists Kathleen Napier and Lior Shamir published a paper in the Journal of Popular Music Studies that showed how between 1951 and 2016 lyrics expressing “anger, disgust, fear, sadness, and conscientiousness [had] increased significantly, while joy, confidence, and openness . . . [had] declined.”

A year later, a paper published in Evolutionary Human Sciences found a similar lyrical trend.

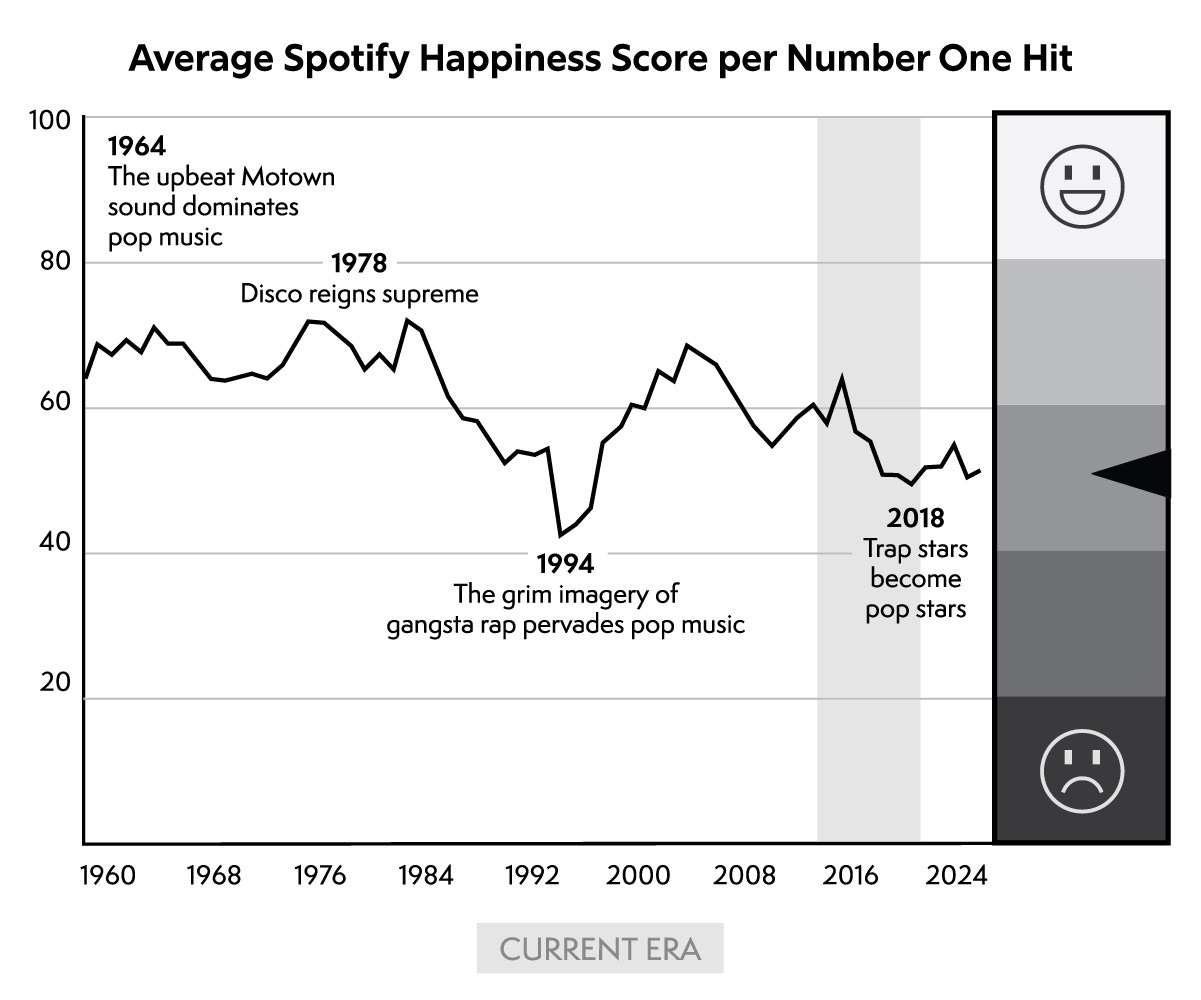

In short, beyond trusting your ears, quantitative evidence suggests that songs were sad in this era. The rub is that this sadness was not new. Most studies suggest that the trend began in the 1980s. If we look at the average happiness score of a number one hit as per Spotify in Figure 12.5, we see this general trend, albeit with significant ebbs and flows.

From 1960 to 1980, Spotify’s happiness score regularly sits around 70. It begins to decline in the 1980s before reaching its nadir in 1994 as alternative rock and gangsta rap take over the charts. Though the score starts to recover during the early 2000s, those gains are wiped out over the next 15 years, falling to 50 by the end of this era.

Of course, this doesn’t mean that every song in this era was laced with sadness. Pharrell Williams’ relentlessly happy “Happy” (March 8, 2014) spent ten weeks atop the charts in this era. But for every “Happy,” there was at least one “SAD!” Literally. XXXTentacion’s relentlessly sad “SAD!” (June 30, 2018) topped the charts almost four years after “Happy.” But why did this music feel so sad?

Sad Tempos

It’s the fall of my senior year of college. I’m out at a bar. Sean Paul starts dictating that the women in the bar “rock with it,” “bounce with it” and “dance with it” as “Cheap Thrills” (August 6, 2016), his collaboration with Sia, starts coming through the speakers. The ladies do indeed start rocking, bouncing, and dancing. I’m kind of a “Cheap Thrills” hater, so I head to the bathroom. When I return, a new song is on: “Blurred Lines” (June 22, 2013), a Marvin Gaye-inspired collaboration between Robin Thicke, T.I., and Pharrell Williams. I’m kind of a hater of this song too. But that doesn’t matter. The people love it, dancing until the bartenders make us go home.

“Cheap Thrills” and “Blurred Lines” are both dance records. But they are very different dance records. “Blurred Lines,” clocking in at 120 beats per minute, is up-tempo and funky. “Cheap Thrills,” with its dancehall-infused rhythm, is a more leisurely 90 beats per minute.

From Drake’s “In My Feelings” (July 21, 2018) to Iggy Azalea’s “Fancy” (June 7, 2014), if people were dancing in this era, they were usually doing it to a tempo more like “Cheap Thrills” than “Blurred Lines.” In fact, 43 percent of number ones in this era were less than 100 beats per minute. Compare that to the period from 1960 to 1989. Only 25 percent of number ones were below that tempo threshold. While “slow” isn’t equivalent with “sad,” musical psychologist Michael Bonshor told Esquire in 2023 that “The most obvious feature of a sad song is the tempo. It tends to be fairly slow . . . like a relaxed heartbeat.”

Sad Keys

In a 2017 paper “The Minor Fall, the Major Lift: Inferring Emotional Valence of Musical Chords Through Lyrics” researchers found that people associate minor chords and minor keys with darker or sadder sounds. Those chords and keys were much more prominent in this era. In fact, from the start of the Hot 100 through 2000, 25 percent of songs were in minor keys. Between 2000 and the end of this era, 55 percent were.

Rihanna’s “Diamonds” (December 1, 2012) proves a good example of minor key sadness. Though the song’s first verse opens with the uplifting line “Find light in the beautiful sea, I choose to be happy,” there is a tinge of somberness laced throughout. Of note, the song is in the key of B minor.

Sad Genres

In the early 1900s, a dark, emotive style started to transform popular music: the blues. Emerging after the abolition of slavery in the United States, the music was characterized by a 12-bar chord progression, hypnotic rhythms, notes bent expressively, and call-and-response lyrics chronicling the anguish of everyday life. A century later, hip-hop’s own form of the blues would come to dominate the charts: trap.

Though it’s a stretch to compare these two genres, they are both good examples of how certain styles are sadder than others. Trap is a branch of hip-hop defined by hi-hats exploding in short bursts at inhuman speeds, booming 808 kick drums that double as bass lines, and dark lyrics focused on street life. “Bad and Boujee” (January 21, 2017), a song where Migos grunt and murmur about “Cooking up dope with a Uzi” over tittering hi-hats and bass drums that could register on the Richter scale, is a quintessential example of the genre.

And I really can’t stress how dark songs in this genre can be. Both Desiigner’s “Panda” (May 7, 2016)5 and Cardi B’s “Bodak Yellow” (October 7, 2017) almost leave me shaking in fear. While scores of other trap songs were popular in this era, its importance was how it influenced other genres. To quote rapper 2 Chainz in a 2017 interview with Rolling Stone: “Trap rap is pop now.”

Halsey injected twitchy trap hats on her moody pop song “Without Me” (January 12, 2019). Taylor Swift did the same on “Look What You Made Me Do” (September 16, 2017). The Weeknd ratchets these elements up on “The Hills” (October 3, 2015), your speakers shaking from an overdriven trap bass line that sounds like it was written for a horror film that takes place in a strip club. These sounds became so prevalent that in 2018, Complex noted, “Now, it seems you can’t find a song without trap hi-hats.”

When you take elements of a grim genre and use them in other styles, that grimness remains. That’s especially true when you consider a few of the more melodic styles of hip-hop that also co-opted trap elements in this era.

Often referred to as some combination of “emo rap,” “mumble rap,” or “cloud rap,” these styles—which proliferated on online platforms like SoundCloud, Audiomack, and DatPiff—traded the wordiness that typically characterized hip-hop for hazy, dreamlike atmospheres.

Both XXXTentacion’s aforementioned “SAD!” and Post Malone’s “Psycho” (June 16, 2018) illustrate this sound. With pittering hi-hats and woozy synths, they feel like hip-hop songs shot with a tranquilizer, MCs functioning more like lethargic singers than rappers. Like trap, songs in these genres are somewhere between ominous, dark, depressing, and angry.

Should I Be Worried about the Popularity of Sad Songs?

If you’ve made it this far in this book, you’ll know that sad songs are nothing new. In Chapter 1, we had a long discussion about teenage tragedy songs. In Chapter 4, two songs about suicide came up. A few chapters after that, we covered the grim imagery of certain hip-hop songs in the 1990s. Still, people often worry about the consequences of dark, depressing music. If my daughter starts listening to emo rappers, will she engage in self-harm? Could my son’s obsession with trap lead to drug use?

I’m not really worried about these things. If you recall The High-Tide/Low-Tide Theory of Popular Music that I outlined in Chapter 2, musical styles usually come in waves. If one dark, depressing song tops the charts, you’ll see scores of otherwise happy artists trying to imitate it. Furthermore, there’s a long history of people worrying that music will lead to unhealthy or immoral behavior. Nearly all those panics amounted to thinly veiled racism or sexism.

This doesn’t mean that music can’t have negative consequences. But self-expression is usually healthy. If you want to scream along to a depressing song, you should. It’s probably a better outlet for your anger or angst than anything else.

Nevertheless, when sad sounds characterize large swaths of popular music, we should consider if there is an underlying cause. These considerations shouldn’t be used to condemn the music. They should be used to make sure that people are okay. During this era, there was a slew of worrying research about anti-social trends among young people. In fact, in an early 2025 article for The Atlantic, journalist Derek Thompson went so far as to call this period the beginning of “The Anti-Social Century.”

While assessing these ideas falls outside the scope of this book, it’s a good reminder to pay attention to the songs people listen to and how they sound. Sometimes, pop music is truly just that, a sugary confection to please your ears. Sometimes it’s a bit more, though.

This was an excerpt from Chris Dalla Riva’s forthcoming book, Uncharted Territory: What Numbers Tell Us about the Biggest Hit Songs and Ourselves. If you enjoyed it, you can pre-order a copy of the book today. And if you think you have a way for Chris to promote the book, please reach out via this form.

Malcolm Gladwell has a episode on his Revisionist History podcast about sad music (Season 2, "The King of Tears"). His contention is that rock and roll doesn't really have sad music the way that country music does. I think he has a point. Rock songs can be dark or depressing, but they don't often have the plaintive lamentations of the blues or the truly emotional tearjerkers that you find in country music (or at least used to find). It's kind of true for pop music too, though I can think of a few exceptions. I suppose it depends somewhat on how you define sad.

Well, I’m about to make some incredible generalizations, but if I had to paint with a very broad brush, I would think that every decade (more or less) is a barometric reflection of the culture at the time. I think of the 1950s, World War II was finally over, Hitler was dead in some bunker, and Japan had been brought to its knees and surrendered. Returning vets were trying to get back with their lives and move on and the music (generally speaking) was fairly happy and lighthearted. Rock around the clock, all that sort of thing.

it didn’t last long, that whole era of political assassinations: Kennedy, Robert Kennedy, Martin Luther King, etc. Vietnam was starting to heat up, people were being drafted to fight what was basically a bullshit war, then Kent State. Richard Nixon was controversial to say the least, and probably half the country hated his guts. Accordingly, music went very heavily into the angry protest movement type of direction, be it folkies or rock groups.

What happened after the Vietnam war ended? Nixon got booted out of office? American went back to happy music, disco specifically. The 60s groups artists were still around, but there had been a significant shift away from them.

I think you basically get my line of thinking and utilizing it you can follow it out decade by decade to where we are now. Young people today face unprecedented challenges in the workplace and culture, which often goes unnoticed by people of my generation. There’s a lot of confusion, young folks are trying to come to terms with unprecedented developments in the culture. (I’m a boomer.) Housing costs are going up everywhere, the introduction of AI into the culture overall and an extremely competitive job market - all that and much more are in full play, so why would the music today be particularly happy today? I not 1% surprised.